“Metaphors in Motion”—Mark 11:1-11

A Sermon for First Church of Christ, Congregational of East Haddam, Connecticut

Palm Sunday, March 25, 2018

When we talk about it, we make it sound like a parade: Jesus’ “triumphal entry” into Jerusalem. We picture crowds lining the streets, even throwing down their garments like a red carpet, waving palm branches, and shouting, “Hosanna! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord.” The heading for this passage added by the Bible translators reads, “Jesus Enters Jerusalem as King.”

But look at the story.

Jesus and his disciples were traveling from Galilee to Jerusalem to celebrate Passover. If we look back in Mark 10, we can see a lot of things were going on. The religious leaders were tried to trick him into a doctrinal trap by asking him questions about divorce. When the disciples tried to keep a group of children from bothering Jesus, he not only welcomed them but said they understood how to open their hearts. “Be like the children,” he said, “and you will understand what it means to follow me.”

After the kids left, a man we have come to know as the rich young ruler came to Jesus looking for validation. “I obey all the law and the prophets,” he proclaimed, even though I think he knew he was missing something. Jesus told him if he wanted to understand what discipleship was about, he would need to give up all his stuff. The man couldn’t do it. He liked his privileged life. So he walked away.

Not long after that, James and John asked Jesus if they could sit on either side of him when they all got to heaven. Though it’s not in Mark’s gospel, Jesus’ response to them almost sounds as though he said, “You did hear what I just told that last guy, right?” He spelled it out clearly: God calls us to serve, not to be served. What am I going to get out of this? is never the first question. And then, when they got to Jericho, he restored the sight of a blind man named Bartimaeus who called out to him as he entered the city. Mark says, once Bartimaeus could see, he followed Jesus, both literally and figuratively; Mark says Bartimaeus “followed Jesus down the road.” Bartimaeus could see what the rich young ruler could not.

When they got to Jerusalem, Jesus gave the disciples rather mysterious instructions about going to someone’s barn and untying their donkey. “If someone asks what you’re doing, tell them, ‘The Master needs it.’” When I was a kid, I thought this story made Jesus sound magic—like he had some sort of mind controlling power. Once the disciples used the magic words, they could have walked off with almost anything. I asked my dad about it one day and he said, “I think Jesus just knew the guy with the donkey.” I had never thought that Jesus might have planned ahead, or had friends other than those listed in the gospels. But Jesus had planned ahed. His ride into town was not spontaneous. He knew how he wanted to enter the city.

The disciples came back with the donkey, made a seat for Jesus out of their coats, and he rode into town. Mark says, “many people” spread their coats on the ground and “others” waved palm branches. Our collective Christian imagination over the centuries has turned this into a city-wide celebration, but I’m guessing it was on a much smaller scale, and not very royal at that. It was a metaphor in motion. A real king would have ridden into town in a chariot, or at least on a fine stallion. He would have been flanked by protection. The point would have been a presentation of power.

Jesus rode bareback on a mule. A farm animal. A beast of burden. And he entered the city with all the pomp and circumstance of a neighborhood parade, except parade implies a procession of some sort. He was not proceeced, protected, announced, or even accompanied. It was just him. Those who lined the street shouted, “Hosanna,” which comes from a Hebrew word that means “save us.” Like Bartimaeus, most everyone was looking for healing.

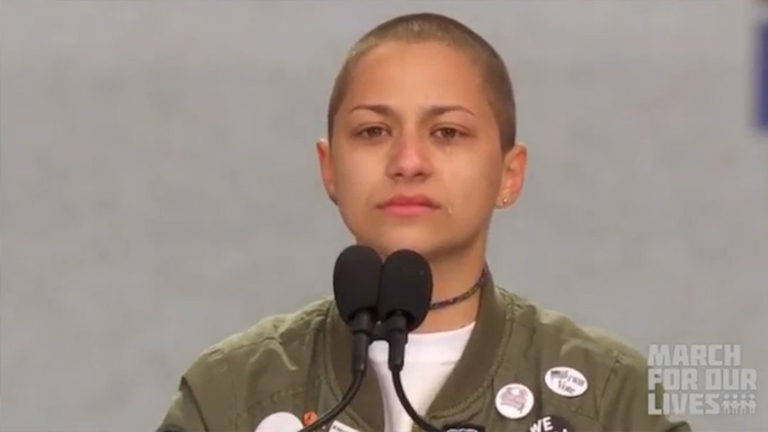

Yesterday, in at least eight hundred cities and towns across America, millions of people participated in the March for Our Lives, a protest calling for a serious and meaningful discussion about how we deal with firearms in our country. My town, Guilford, was the location for the Shoreline gathering because the Guilford Green is large and because our town has been affected directly by gun violence in recent days. In late January, one of our teenage boys was accidentally killed by a gun belonging to a friend’s father, who failed to keep it locked up.

I have no idea how many people were there, but it was the largest crowd I have ever seen on our green. I saw reports this morning that estimated two to three thousand gathered to hear speakers and singers. The organizers worked hard to make our informal gathering a meaningful one. And it was. The march itself was rather ceremonial: we walked a little less than a mile and ended up back where we started. But it, too, was a metaphor in motion: it was a wake-up call, an incarnational statement that we trust if we show up and listen to each other, we will find healing.

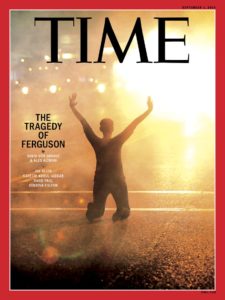

Ginger, my wife, was one of the speakers and she made a point of recognizing the privilege of those of us gathered there. Last night, I listened to Naomi Wadler, an eleven-year old who spoke at the March in Washington. She said she wanted to speak for the African-American women and girls who are victims of gun violence but never make the front page. Then she said,

It is my privilege to be here today. I am indeed full of privilege. My voice has been heard. I am here to acknowledge their stories, to say they matter, to say their names, because I can, and I was asked to be. For far too long, these names, these black girls and women, have been just numbers. I’m here to say, “Never again” for those girls, too. I am here to say that everyone should value those girls, too.

Jesus saw most everything around him. Because Jesus was astute and perceptive, I think he knew his entry into Jerusalem was anything but triumphant. He knew he was on the wrong side of the religious leaders; he knew the government considered him a menace, an instigator. And he knew his disciples were still struggling to understand who he was and what was happening. He knew he was not walking into a happy ending. It would have been easy for him to despair, or to become cynical. He had poured his life into his disciples, and they wanted him to pick a favorite. As the crowd shouted, “Hosanna,” I wonder if Jesus felt encouraged or defeated. It’s hard to tell. He doesn’t say a word.

At our march in Guilford, speaker after speaker went back over the list of mass shootings: Columbine, Sandy Hook, Las Vegas, Orlando, Parkland—I know I am not listing them all. Almost all of them lamented that after each one there has been a cry for something to be done and nothing has happened. This time, it seems, the teenagers of this “mass shooting generation” are old enough to respond and to take action. They bring energy and hope when those of us who are older have settled for cynicism and despair. They are taking to the streets of our towns and cities and call us to believe that things can change, that we can be healed.

I am not saying these kids are our messiahs as much as they offer us a lens through which to see Jesus. The people who lined the streets to welcome him came to Jerusalem every year for Passover, and every year the Romans were still in charge. That they were remembering their deliverance from Egypt while they were under Roman occupation was a bitter irony that was not lost on the Jewish people, I’m sure. And, when they shouted, “Save us,” to Jesus, I’m not sure they expected much.

But Jesus did. He believed it mattered that he was riding into town. He planned for everything down to the donkey and then he set things in motion. As he had said to James and John, he had come to serve—to give his life for others. Now he was showing them what that looked like.

If Bartimaeus did follow Jesus all the way to Jerusalem, maybe he was one of the first ones to begin to shout, much as he had done in Jericho. “Hosanna. Save us.” On this Palm Sunday, two thousand years of sadness and violence later, we are still singing the same song. “Hosanna. Save us.” As I stood on the Green yesterday, and listened to person after person call for things to change, I could hear it in our voices. “Hosanna. Save us.”

When Bartimaeus first cried out for help in Jericho, Jesus asked, “What do you want me to do for you?”

“I want to see,” Bartimaeus answered.

“Go,” Jesus said, “your faith has healed you.”

What Bartimaeus saw was that healing is hard work. The next few chapters in Mark’s gospel are filled with Jesus’ words, and most of them are not easy to take, or even to understand. There’s a good chance some of the people shouting “Save us” as Jesus entered Jerusalem were crying “Crucify him” by the end of the week. Once we are given eyes to see our world as Jesus does, we are called to be healers too.

To heal the violence in our country will take more than gathering on the Green. It will be hard work. That’s what we have to plan for. That’s what we have to choose to do. We cannot walk away like the young ruler and take shelter in our privilege. In our world of violence and grief, we need to offer not just our thoughts and prayers, but our thoughts, prayers, and actions. We need to move beyond our privilege and risk losing to serve those around us. We need to open our hearts like the children we saw and heard at the marches yesterday. Jesus is calling us to wake up, stand up, and follow him down the road—to be metaphors of motion, incarnations of God’s love, carriers of hope and healing. Let’s follow him down the road. Amen.

Peace,

Milton