I preached this morning at United Churches of Durham, Connecticut as a part of a pulpit exchange between our church and two others. My sermon is my offering for today.

“An Unreasonable Request”—Mark 8:31-38

At the risk of bringing up painful memories for some of you this morning, I invite you to step out of church for a minute and go back to English class. Can someone tell me what a metaphor is?

I’ll help you out: a metaphor is a comparison of two things that are not alike as a way to explain or give meaning to one of them. Examples work better than definitions.

America is a melting pot. (No one is actually melting.)

Life is a rollercoaster. (It has its ups and downs.)

Their home was a prison. (You get the picture.)

The world is a stage. (Not necessarily good news to introverts.)

My kid’s room is a disaster area. (This one might be literal in some cases.)

Metaphors work when people understand both sides of the comparison. If I were in a country that had no amusement parks, saying life is a rollercoaster might not get me too far. Jesus’ teachings are filled with metaphors and similes, and some of them are lost on us because we live in a different time and a different place. Jesus talked about people being sheep because the hills of Galilee were filled with them. When he called himself the Good Shepherd, most everyone in the crowd knew a shepherd personally. Most of us need the metaphor explained to get the full meaning and, in some ways, a metaphor is like a joke: if you have to explain it, it loses something.

That said, when we read the words of Jesus two thousand years after they were written down, what else can we do but try to explain them to one another? We not only have to try and look back to see his words in the context of his culture, but we must also do the work of seeing how the world we live in now affects how we read and hear the words. Two millennia later, and thousands of miles from Palestine, how do we hear these words?

All who want to come after me must say no to themselves, take up their cross, and follow me. All who want to save their lives will lose them.

When we hear the word “cross”—at least in church—we are well-conditioned to think of Jesus’ crucifixion. Yet those who heard Jesus say these words knew nothing of his coming death. He tried to warn them that he was on a collision course with those in power, but they didn’t get it. For those gathered around Jesus, the cross was an instrument of execution—and a brutal one at that. Imagine Jesus saying, “You have to go to the electric chair,” or “You have to take a lethal injection.” So what did Jesus mean by the metaphor?

The conversation between Jesus and the disciples that we read this morning took place after they had seen him feed four thousand people when there appeared to be hardly any food at all. After lunch, Jesus warned them “to be on guard for the yeast of Herod and the Pharisees”—another metaphor they didn’t get. They thought he was literally talking about bread. Jesus became frustrated and peppered them with questions:

“Why are you talking about the fact that you don’t have any bread? Don’t you grasp what has happened? Don’t you understand? Are your hearts so resistant to what God is doing? Don’t you have eyes? Why can’t you see? Don’t you have ears? Why can’t you hear? Don’t you remember? When I broke five loaves of bread for those five thousand people, how many baskets full of leftovers did you gather?”

They answered, “Twelve.”

“And when I broke seven loaves of bread for those four thousand people, how many baskets full of leftovers did you gather?”

They answered, “Seven.”

Jesus said to them, “And you still don’t understand?”

Soon after, Jesus healed a blind man, but it happened in stages. Mark says Jesus rubbed spit on the man’s eyes and asked what he could see. “People are walking around like trees,” the man answered. So Jesus touched his eyes again and the man could see clearly. Yes, another metaphor—this time in the form of a miracle.

Then Jesus asked two more questions. First, he asked, “Who do people say I am?” The disciples mentioned Elijah and John the Baptist, among others. Then Jesus asked, “Who do you think I am?”

Peter answered, “You are the Christ.”

Jesus then told them he was going to suffer at the hands of those in power and die. Mark says, “He was speaking clearly.” No metaphors. Peter, who had just made his triumphant claim about Jesus being the Messiah, would have none of it. He responded forcefully, even violently. The gospel says Peter “took hold of Jesus and, scolding him, began to correct him.”

Jesus responded in what is most often translated as, “Get behind me, Satan,” but he wasn’t calling Peter the devil. The Greek word was used to describe a legal adversary, or prosecutor—someone who spelled out the letter of the law. That’s right: another metaphor. Jesus was saying, “Don’t fight me on this. Don’t reason with me. Listen.” Peter was trying to protect Jesus—and himself—and Jesus responded by saying, take up your cross and follow me. Lose your life to find it.

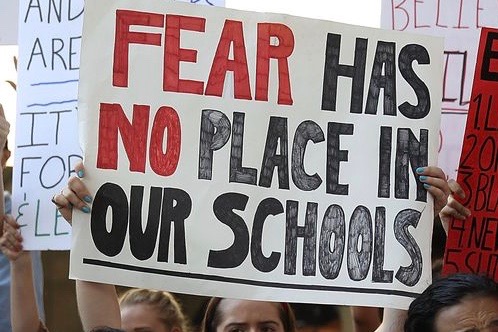

Jesus spoke those words in his context and we hear them in ours. How then do we hear Jesus’ call to lose our lives in the wake of the latest school shooting? What do we see in Jesus’ words that the last shall be first in a culture that has little use for anyone but winners? What does it mean to take up our cross in our time and our culture?

This past week I was part of an exchange on a Facebook thread with someone I don’t know—a friend of a friend. I was writing about banning assault weapons and he was arguing that people had a right to guns. After we went back and forth a couple of times, he said, “Please argue from reason and not emotion.” It strikes me that he was saying the same thing Peter was saying to Jesus. Let me be clear: I’m not saying I’m Jesus in this scenario. I am saying that Jesus’ call to take up our cross is not a reasonable request. It is a call of passion, compassion, and emotion. It is a call to choose love over fear is neither logical nor dispassionate. Choosing love is not a reasonable act, and it is also more than an emotional response. Love is an act of will, an intentional decision to defy all that pulls us apart. Whatever the conversation is, if we lead with, “I have a right to . . . ,” we miss the call of Christ on our lives.

Well, let me make an exception to that statement. If you are in an abusive situation, it is not God’s will for you to stay there and “lose your life.” Abuse, in any form, is not a cross to bear. That is not what I am talking about here.

If we begin talking about gun violence by saying, “I have a right to bear arms,” or we begin talking about the need for affordable housing in our communities by saying, “That will affect my property value if they build next to me,” or we begin the immigration discussion by saying, “I was here first,” or we begin the discussion about economic justice with, “Well, I worked hard for what I have,” then we are missing the meaning of Jesus’ metaphor.

Lose your life to find it, Jesus said. He wasn’t being literal there either. We cling to what is ours when we think we are not safe, or when we think we will not have enough. To lose our lives—to choose to respond to the brokenness of the world out of love rather than fear—means to trust that God’s love is stronger than fear.

When students around the country began planning protests and walkouts to break the stalemate in our discussion about gun violence, a number of school districts banned the protests and said any students that participated would face detention or suspension. Getting zeros for four or five days of classwork might change someone’s GPA or affect a semester grade. It could, I suppose, affect college admissions for some. School officials thought they could scare the students into compliance. The students are still walking out. They are living metaphors, losing something to find something far more valuable. And they are offering us a chance to see with new eyes.

To take up our cross means to embrace the unreasonable truth that the primary point of faith and of life is not to make sure we are safe and taken care of before we act on someone else’s behalf. The metaphor is clear: to live a life of faith in Christ will cost us our lives as we offer them to one another, but, like the handful of loaves that fed thousands, our willingness to share more than our leftovers creates abundance. Our willingness to voluntarily share each other’s pain brings peace that cannot be explained. When we lose our lives in one another, we find life more abundantly. Don’t be reasonable. Choose love. Amen.

Peace,

Milton