I started reading the Gospel of Mark yesterday as a part of my morning reading time.

I got a copy of David Bentley Hart’s new translation and took it as an invitation to dive back into the Gospels once again. Hart is an Eastern Orthodox scholar of religion and a philosopher. In his introduction to the translation, he talks about wanting to create a sense, in English, of what it felt like to read the books in Greek. None of the gospel writers was a wordsmith or a poet. They are not consistent with their verb tenses; their sentence structure is often awkward. They were writing with urgency and passion, and without a style guide.

I thought of Pádraig Ó Tuama’s observation that translation is often colonization: we make the words say what we want to hear.

But what got me this morning was not the big ideas, but a word and a phrase. What follows is a rather rambling account of where they took me.

In Mark 6, Jesus sends the disciples away after the feeding of the five thousand by telling them to row to the other side of the Sea of Galilee, disperses the crowd himself, and goes up the mountain for some alone time before he meets back up with his followers. They were not on the water long before they found themselves rowing into a formidable headwind. They kept rowing, but they weren’t getting much of anywhere. It was after midnight and they were still at sea. Then Jesus came walking by–and I mean they thought he was just going to walk right by them. They cried out.

Hart translates what happens next:

For they all saw him and were disturbed. Immediately, however, he spoke with them, and says to them, “Take heart, it is I, do not be afraid.” And he went up to them, up into the boat, and the wind ceased; and within themselves they were quite overwhelmingly astonished. For they did not understand about the loaves, while their hearts were obdurate.

I had to look up the last word.

Obdurate: stubborn, impenitent, unrepentant, “refusing to change your opinions or plans, in a way that does not seem reasonable.”

Most of the translations I have read over the years read like the NRSV: “And they were utterly astounded, for they did not understand about the loaves, but their hearts were hardened.”

My new vocabulary word made me look back at what led up to Jesus wanting to get away. He had been trying to get away ever since he got word that John the Baptist had been capriciously murdered by Herod, but everyone followed him wherever he went to the point that he and the disciples ended up in the desert outside of town with a teeming, hungry crowd. When the disciples said Jesus needed to send them home for dinner, Jesus’ response was, “You feed them.”

Mark gives no indication of the tone in Jesus’ voice when he said those words. When I think of the rawness of his grief at the loss of his friend, I hear frustration and exhaustion: you do it; quit asking me.

What happened next is the part of the story we all like: a boy had a sack lunch of bread and fish, Jesus blessed it, the disciples started handing it out, and they ended up feeding thousands–with leftovers.

Immediately–while the folks were still finishing dinner–Jesus insisted the disciples get in the boat and head across to the other side, where he said he would meet them. I have never paid much attention to the nature of his insistence. But I keep coming back to Jesus’ grief: go; just go.

The Gospels have a couple of stories that involve, the disciples, a boat, the weather, and Jesus. I have to work to keep them from conflating. On this night, there was no storm, just a vicious headwind. After Jesus came back from where he was praying, he saw them flapping in the breeze and walked toward them–but I already told this part: “Take heart, it is I.”

When Jesus got in the boat and the wind stopped, the disciples were astonished and obdurate. Mark says they “didn’t understand about the loaves, while they were obdurate.”

Miguel de Unamuno says, “There is no proof that the true is necessarily that which suits us best.” What was it about the loaves and fishes that made the disciples dig in their heels, even in their astonishment?

I want to go back to Jesus saying, “You feed them.” I hear more than just grief.

The disciples answered by saying they didn’t have the time or money to go buy for for everyone. Jesus asked, “How many loaves do you have?” And dinner unfolded from there. The second question resonates with the spirit of “Take heart, it is I; do not be afraid,” which came as the disciples were feeling completely overwhelmed for the second time in a half a day.

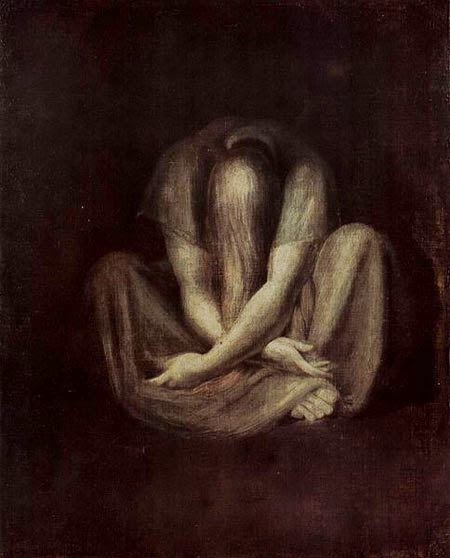

Maybe they were obdurate not because of Jesus’ questions and requests, nor by the circumstances of the crowd and the wind on the water, but because of a lifetime of believing that nothing was ever really going to change. Miracles and messiahs come and go–they knew that. Their hearts had grown hard because they had spent their whole lives hungry and fighting a headwind. Life felt like a choice between fear and impenitence. They didn’t understand that what Jesus did with the bread was more than a miracle meal. It was an invitation to way more than dinner.

As many of us are learning in new ways in these days, life is not easily explained. Sometimes we stumble on abundance when all we can see is desert. Sometimes Jesus shows up when we are being beaten by a headwind. Sometimes emptiness appears when we are hoping for fulness. Grief shows up and just stays. Questions appear when we thought what we needed were answers.

Take heart. And keep rowing.

Peace,

Milton