I preached this morning at our church in Guilford, and it was another peach of a passage as far as the lectionary is concerned. I had to write the sermon in traffic, as I like to say, because it was a hectic week, but some of those things became part of what helped me to see the verses in a new light. Since my interim is over, this is my last scheduled sermon for a while. I hope you find something here that speaks to you.

________________________________

Last week, I started publishing an online newsletter called “mixing metaphors.” Actually, Ginger was the one who came up with the title because, she said, it’s what I do. I like to mash up ideas and images that offer the chance for imaginative conversation about what it means to be human.

As long as my mother was alive, she admonished me to be like Jesus. After dealing with today’s passage and the parables that surround it, I wish I could tell her I think I’m pretty close because in the eight verses we read Jesus gives us a festival of mixed metaphors.

First, he said, those who did not hate their families could not be disciples. Then he said those who did not carry their cross couldn’t either–and they knew nothing about his upcoming crucifixion, so what that metaphor meant to them is up in the air. Maybe it had more to do with the weight of empire, since Rome used crucifixion as punishment for crimes, than our image of great sacrifice. Then he switched to talk about counting the cost of building a tower and counting the cost of going to battle against a more formidable opponent, and then he said, “Therefore, none you can become my disciple if you do not give up all of your possessions”–and then, in the following verses that we did not read, he said we were like salt. He hit everything from siblings to seasonings as he talked about what it means to be human.

Look, Mom, I’m like Jesus . . . ?

At least, I hope so.

But I have to tell you, when I read phrases like “must hate your family” and “renounce all your possessions,” I wonder what to do with them even though Jesus said them.

I have watched, for example, as some maliciously use the two stories about counting the cost to castigate those who have had their student loan debt forgiven, and part of me wishes those words of Jesus weren’t even written down so they could not be weaponized.

Though the gospel writers rarely give us any indication of Jesus’ tone when he spoke, I have been turning these words over all week listening for something that offers more than Jesus telling everyone they were a huge disappointment to God.

Then I saw something I had not seen before. Listen again:

For which of you, intending to build a tower, does not first sit down and estimate the cost, to see whether they have enough to complete it? Otherwise, when they have laid a foundation and are not able to finish, all who see it will begin to ridicule them, saying, ‘This person began to build and was not able to finish.’

Jesus said the reason the person had for making sure they could finish the tower was so they would not be ridiculed for a half-built tower. And the second story:

Or what king, going out to wage war against another king, will not sit down first and consider whether he is able with ten thousand to oppose the one who comes against him with twenty thousand? If he cannot, then while the other is still far away, he sends a delegation and asks for the terms of peace.

The result of the king measuring his army against his opponent’s was to decide the battle wasn’t worth it and to send a peace delegation instead.

The characters in both stories are examples of vulnerability, not victory. The first had a big idea that got knocked down by things they didn’t see coming, and the second had delusions of grandeur that were cut down to size in a moment of reflection.

The way Jesus talked about the kind of commitment it took to be a disciple, he seemed to say that there is not a way to communicate just how much it costs.

We can give lip-service to putting our commitment to God above family and possessions, or anything else for that matter, but living that out is a different thing, as is figuring out what that looks like. The truth is our lives are littered with lots of half-built towers and battles we didn’t fight. And most all of us are attached to our stuff.

These verses read, it seems, as if hardly anyone measures up as a disciple. But these verses don’t stand alone.

Just before this mess of metaphors, Jesus told three parables about banquets. One is about someone who goes to a banquet and tries to switch place cards to worm their way up to the head table only to be moved to the back (and Jesus said don’t be like that); one is about someone who hosts a banquet and only invites people they think will invite them back only to learn that doesn’t pay off (and Jesus said don’t be like that); and one is about someone who sends out invitations to a banquet to people who were used to going to banquets, and everyone responds with silly excuses, so the host instructs their servants to go out and find anyone who is hungry enough to come and eat (and Jesus said be like that).

In the chapter that follows our verses, Jesus tells three parables of people who appear to not count costs: a shepherd who leaves his flock of ninety-nine sheep to go out in the night to find one that had gotten lost; a woman, who loses one of the ten coins she possessed, tears up her house looking for it, and then blows her whole budget throwing a party for the neighborhood to celebrate; and a father who pulls out all the stops when his son, who had disowned him, comes home after losing everything because he has nowhere else to go.

The traditional reading of these last parables is that God is the extravagant one—and that is true about God. But what if we put ourselves in the place of the shepherd or the woman or the father? What if we think of these parables in the light of Jesus’ call to give up our possessions?

Perhaps what is missing in our understanding of what Jesus was saying in these parables is that Jesus understood most of us spend their lives counting costs. We measure our steps and choose our words; we run scenarios in our minds and make forecasts and predictions. We want to make sure we are safe. We want what is coming to us. We don’t want to get taken advantage of. We want to share, but we don’t want to give up too much.

The truth is that kind of math doesn’t add up because we can’t see what’s coming. What we can see are the invitations life is offering us right now—invitations to incarnate the love of God to those around us in tangible ways.

Our friends Jena and Marc felt compelled to pay for a student from A Better Chance (ABC) to go to college. When Julie became our foster daughter, they also gave us one of their cars because they knew we were going to need a second vehicle. They had the means to do both—and they were willing to do them.

Sometimes, the call to respond is more celebratory. Our goddaughter Ally and her partner Pete opened a restaurant in Athens, Georgia this week. As you can imagine, the opening was the result of years of dreaming and planning. Thanks to Avelo Airlines, we were able to figure out how to get there—and it mattered to her that we did.

At the same time, Ginger’s cousin in Alabama is facing a housing crisis and has nowhere to go, so we are in the process of adjusting some of our plans to buy a small place so he will have somewhere to live.

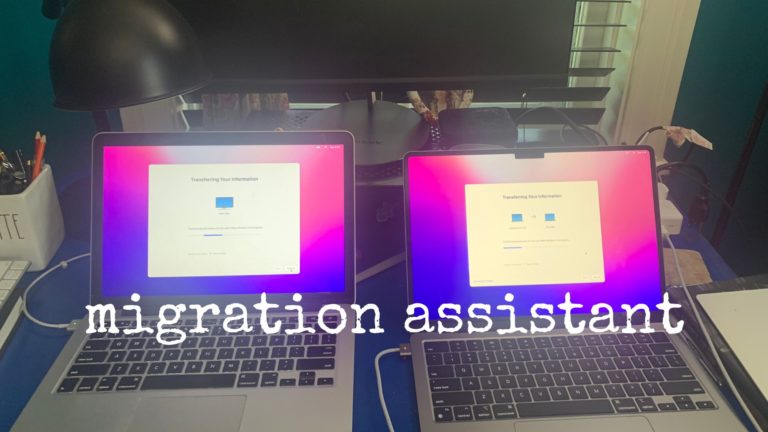

As I was working on my newsletter and trying to figure out life after my editing job, a person who I know through my blog but have never seen face to face spent two or three evenings after work helping me sort through some technical stuff I did not know how to do just because I asked.

I wish we had time to let the people here tell stories because I am sure this room holds many tales of ways people have been extravagant to us and ways in which we have counted the cost of what it means to be family or friends and then paid the bill.

Take some time to think of those stories and tell them to one another. They are stories of discipleship, if you will.

Jesus told these parables in response to questions that came from those who were critical of him: Why did you heal that man on the Sabbath? Why do you hang out with tax collectors and sinners?

Jesus’ answer was basically to say, “Why not spend my life on them? What else is going to add up to a life worth living?”

As followers of Christ—disciples—we are called to pay the cost of noticing one another, of witnessing one another, and attending to one another, of loving one another. We are called to offer our half-built towers as shelter, to share our daily meals as if they were banquets, to find one another no matter why we got lost in the first place for no other reason than that’s what Jesus did. And, like my mother said, we ought to be like Jesus. Amen.

Peace,

Milton

My writing here and in my newsletter are offered for free, thanks to the help of my members who help to support me. You can subscribe to my weekly newsletter (which is also free) and become a member. Thanks for reading.