Here are the words I spoke at my mother’s funeral:

When my father died, I adapted a poem I had written for him a few years earlier, which allowed me to tell his story, express my feelings, and get through the whole thing without breaking down here at the podium. To my disadvantage today, I didn’t have a poem on hand for my mother. The memories and stories of her are stuffed in my mind and my heart like the pieces of paper crammed into one of the notebooks we found in her apartment this week, and they are full of emotion. There is so much to tell, so much for which to be grateful. What then shall I say?

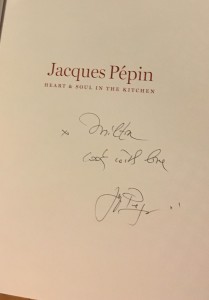

My earliest recollections of her are in the kitchen. She loved to cook, and she loved to have people around her table. Both are things she passed on to me. So I thought the best way I could organize the thoughts and stories crammed in my brain would be to offer a recipe for the life of Barbara Cunningham.

Like the best recipes, this one is simple. First, set the temperature of her life to tenacious. My mother loved being alive as much as anyone I have ever known. She was unflappable in her energy and determination. Whether it was telling first dates at Baylor that if they didn’t want to spend their lives in Africa there would be no second date, or pulling out her Texas drivers license during the Zambia Independence celebrations so that she could pass as a reporter for the Dallas Morning News to get into one of the festivities, or looking at the doctor when he came to visit her in hospice and saying, “If my goal is heaven, what do I need to do?”, she was going to get what she wanted. When he heard her choice to go into hospice, her primary care doctor said, “You have made a choice of courage and hope and not of despair.” Set the temperature on tenacious.

The first ingredient is a contagious faith. She wanted, more than anything, to tell people about Jesus. And she did, right down to the very end. It seemed every time she got on an airplane she came home with another story about someone she had called to faith in Christ. The story never stopped there, however. She had an amazing way of keeping up with those folks whom she had met through chance encounters. She wanted to know what happened after that first meeting, which leads me to my next ingredient: a hunger to connect.

My mother loved connecting with people and then connecting people with one another. One of her visitors in hospice this week was a Baylor student who came with his mother—they had driven all the way from Nashville. Mom found out he was interested in becoming a dentist. A couple of hours later, I came back into the room after stepping out to give her time with others who had stopped by. Mom told me to find her address book and call the young man because she had found him an internship with her dentist who had just left the room.

As I mentioned earlier, her love of cooking grew out of this hunger to connect. The table was a way to bring people together, o there was always room at the table for whomever she could find. Meal time was an event to be celebrated, even if it was just the four of our family eating ham sandwiches. It was also a time to try new things, which points to the next ingredient in this recipe.

A love of learning and a willingness to fail. I know—that’s two things, but I think they are tied together, particularly in my mother’s life. She loved to try new things. One of Dad’s favorite stories was about my mother getting ready for a big dinner party, which was only a day or two away. She was still figuring out the menu. They turned out the light and she said, “What have you ever seen done on top of a chicken?”

A party was not the time to pull out old favorites; it was time to make a leap of faith, to go out on a limb, and if people didn’t speak up soon enough she would say, “Isn’t this good?”

And it was.

Around the time she turned eighty, she started taking piano lessons, partly because she regretted not doing it as a child, but also because she just wanted to learn something new. There was always room to grow.

Next we add an adventuresome spirit. When my folks were at Westbury Baptist Church in Houston, there were parents that would by my mother a season pass to Astroworld so she could take their kids to ride the rollercoasters. One year they built a big new wooden coaster and advertised a free t-shirt if you rode it ten times in one day. Mom took several middle schoolers to the park. About ride number seven one of them said, “You go ahead, Mrs. Cunningham. We’ll just sit here and wait for you.” She got her shirt.

The last ingredient is an extravagant sense of generosity. She not only shared what she had, but she looked for ways to help you share what you had, too. When she realized she was not going to be able to go back to Africa to live out her days working in an orphange, we all go letters inviting us to help buy blankets and supplies. Over two years she raised almost $60,000. One of the things of which she was most proud is the scholarship fund at Truett Seminary named for her and my father because it was a way to keep on giving and a way to stay involved with missions and with Africa. And if she were here today, she might remind you that you can still contribute so that we can fully fund the scholarship. I’m sure the ushers will be glad to take your checks.

Set the temperature on tenacious and add a contagious faith, a hunger to connect, a love of learning and a willingness to fail, an adventuresome spirit, and an extravagant sense of generosity, and couch them in the love of a lifetime she found in my father and throw in that she was never afraid to both repeat and embellish a story, and you’ve got Barbara Cunningham, a recipe she was always willing to share.

If you would like to see the service, you can find it here.

Peace,

Milton