I finished a book and started a book today. It was a good day.

The first was Bandersnatch: An Invitation to Explore Your Unconventional Soul by Erika Morrison, which I began reading before we left Durham, packed it by accident, and just got back to it this week. By redefining four words—avant-garde, alchemy, anthropology, and art—she issues a rather vibrant call/invitation to engage God and the world in some fresh and challenging ways. As I reached the final pages, I found myself glad to know she lives in New Haven. I hope we can find some time for conversations that might serve as sequels to my reading.

Morrison reframes anthropology as

a radical way of seeing everyone as if you lived inside their skin and everything else for its full potential. . . . The kingdom anthropologist will always see the stuff of earth as an artery to the kingdom of heaven. The stuff of earth and the stuff of heaven were made for each other. Each gets us to the other. (126)

I love the last sentence in particular. The interconnectedness. And she continues,

The most fundamental premise a kingdom anthropologist holds is this: We are all connected. . . . I start to wonder if most of society lives under the basic assumption that we are all separate, that we are not connected at any level, let alone fundamentally. . . . The anthropologist sees that all people are instrinsically linked not just with one another, but with the entire created order, and seeks to generate a spirit of connection instead of division throughout the land. (153-54)

She then spends some time talking about the food pantry where she and her family volunteer, and she says:

Somehow we all know we’re chained into one another’s lives, stale dreams and broken seams and all. Our individual ships are sinking, but together we manage to stay afloat one more day. (166)

Another last sentence to fall in love with. Knowing I would finish her book on the train to New Haven this morning, I grabbed an old friend off the shelf to read once again: Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art by Madeleine L’Engle. As I started the section on Art in Morrison’s book, she quoted from the L’Engle book that was sharing space in my backpack. I put one down and picked up the other. A chapter or so into reading, I came across a section I have quoted on several occasions without being able to remember exactly where it was:

But I am a story-teller and that involves language. . . . When language is limited, I am thereby diminished, too. . . . In time of war language always dwindles, vocabulary is lost; and we live in a century of war. . . . The diminution is world-wide. (37-8)

Then she moves to a powerful warning:

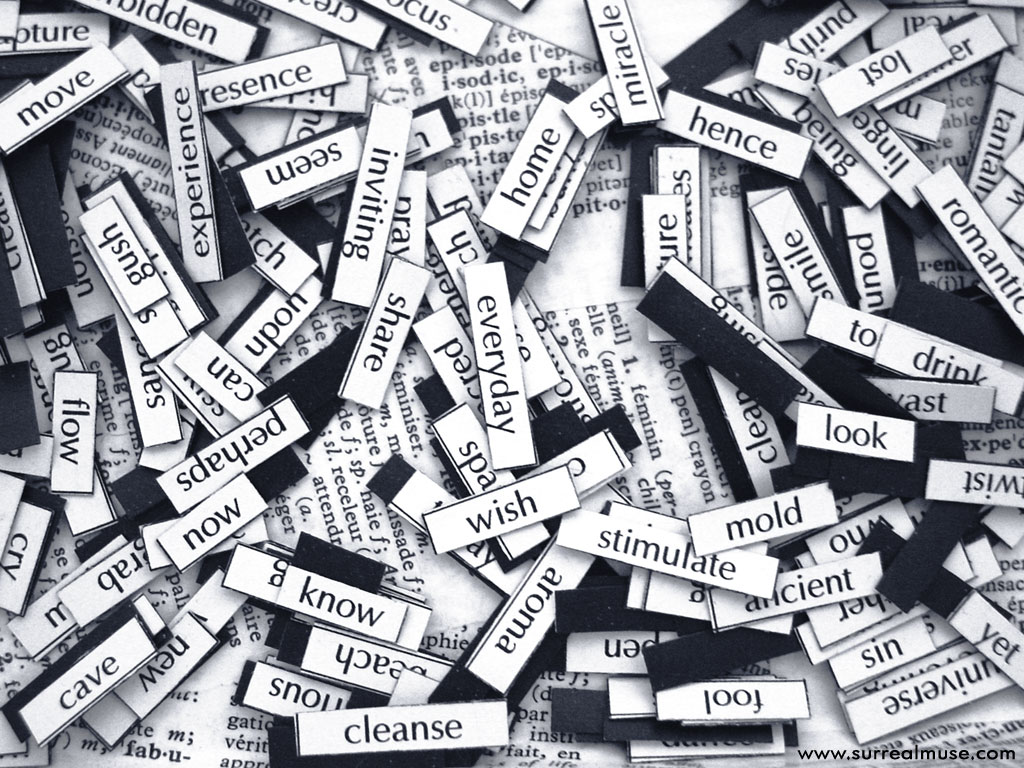

We think because we have words, not the other way around. The more words we have, the better able we are to think conceptually. . . . We cannot Name or be Named without language. If our vocabulary dwindles to a few shopworn words, we are setting ourselves up for takeover by a dictator. When language becomes exhausted, our freedom dwindles—we cannot think; we do not recognize danger; injustice strikes us as no more than “the way things are.” (38-9)

Though I love a good hashtag, the combination of war as common circumstance, technology, and social media have caused our expectations and understanding of language to dwindle. One of my favorite episodes in Ken Burns’ The Civil War was the one that contained Sullivan Ballou’s articulate and heart-wrenching letter to his wife. Today his letter might be reduced to “luv u 4ever. #windonyourcheek.”

The awareness that our vocabulary is shrinking even as our world becomes more complex alongside of the challenge to reclaim and reinterpret words we have know a long time has been energizing to me. One of the things that gets lost when our vocabulary is reduced is a way to express the ambiguity and nuance at the heart of what it means to be human. There is more to life, and to most any issue or topic, than two polarized extremes. L’Engle quoted the Spanish philosopher Unamuno:

Those who believe they believe in God, but without passion in the heart, without anguish of mind, without uncertainty, without doubt, and even at times without despair, believe only in the idea of God, and not in God himself. (32)

My mind is going in a number of different directions with all of this swirling around. The tether between them all goes something like this: the stuff of heaven and the stuff of earth were made for each other—we are all connected—our individual ships are sinking, but together we manage to stay afloat one more day—we cannot Name or be Named without language—and then I ended up at an old Bee Gees song from a record I bought in 1969: its only words, and words are all I have to take your heart away.

One of my brother’s maxims is “the one who frames the question wins the argument.” Morrison pointed out that the perspective that we are all connected runs counter to the societal claim that we are different and at odds with each other. Rather than framing life as a conflict fed by the language of exclusion and division, let our chosen words shine a light on all that connects us. Rather than allowing war to be our primary metaphor and fear our chief currency, let us choose words that paint a picture of the world as a giant artists’ colony, exploding with creativity and cooperation. Rather than using words as weapons, let us choose a healing vocabulary.

Come. Let’s find the words.

Peace,

Milton

Ah, Milton. Grateful for this on a foggy south Texas morning.