I am a few days late posting my sermon from last Sunday, but here it is.

“A Forgiving Air”

Genesis 32: 3-12, 22-32

A Sermon for The United Churches of Durham, Connecticut

August 6, 2017

To say their relationship was difficult would be an understatement. Jacob, the younger brother, had cheated Esau out of the blessing due him as the oldest son. Then Jacob fled, at his mother’s urging, because Esau was so angry. The air, you might say, was thick between them. Jacob changed his location, but not his conniving ways. He always seemed to feel he had to play the system, somehow. It was in his name: Jacob means supplanter—which is not a word we use often these days—how about circumventer, overreacher, deceiver. Almost from the beginning he thought that if he was going to get what he thought he deserved, he was going to have to make it happen. No one was going to give it to him. He was last in line, even though it was a line of only two. He had to get to the front so he could grab it all. Even though he ended up quite wealthy, and married to the woman he loved, it was not enough. There was never enough.

Esau’s name means hairy; some say it’s Hebrew word play on the word red, like the desert soil. He was an outdoors guy, a man of the desert. A hunter. Things were what they were. There was not a lot of ambiguity in the desert. He gave up his paternal blessing for breakfast because he was hungry. Only later did he realize Jacob had stolen him blind.

Where we join the story, Jacob and his whole family are on the move again—this time because of a “misunderstanding” with his father-in-law Laban. The whole crew—family, servants, livestock—are in flight when some of the servants bring word that Esau is on his way to meet him. With four hundred men. As far as Jacob was concerned, that could only mean Esau was coming for his long-awaited revenge. Jacob tried to think of some sort of deception, and ended up sending an overflow of gifts in Esau’s direction and then sending everyone else in the opposite direction to camp across the river Jabbok. Then, he settled down for the night to wait for daylight and the coming confrontation with his brother.

As we read, some time in the night an unidentified man showed up and began to wrestle with Jacob. They struggled the remainder of the night, under whatever star shine there might have been, until—at daybreak— the man yanked Jacob’s hip out of joint and Jacob hung on for dear life to the point that the man pleaded to be released.

“Not until you bless me,” said Jacob.

The man responded by saying, “You are no longer Jacob; you shall be called Israel.” Jacob had a new name. He was no longer to be known as the deceiver, but as one who had prevailed with God. One who hung in there. One who didn’t hit and run. The man disappeared—we are not told anything else about him. Jacob built an altar because, he said, he had seen God face to face. He walked away broken and blessed.

Most of the time, as with our lectionary passage this morning, this is the point where we stop and talk about what the story means; we often talk about how God works through our suffering, how we struggle to come to repentance, or how our woundedness deepens our faith and compassion. All of those thoughts have merit and meaning, yet the story between Jacob and Esau doesn’t end in the dusty dawn on the banks of the Jabbok.

As the night air turned to dawn, Jacob looked up and saw Esau and his whole entourage coming across the desert. There was nowhere to go. No other cards up his sleeve. Instead of wrestling, he fell to the ground in apparent submission. Esau picked him up and hugged him. Hard. There was no trace of anger in the man. No bill to pay for all Jacob done to his older brother. Esau asked about the family he could see gathered on the other side of the river. He asked why Jacob had sent all the stuff, and Jacob was honest enough to say he was hoping to buy favor with his brother. I love Esau’s reply:

“I have enough, my brother; keep what you have for yourself.” (33:9)

Enough. I’m not sure that was a word Jacob understood. He had never had enough. He had never been enough. Even with his flocks and family in abundance, he had—only hours before—been begging desperately for a blessing. Now, face to face, his brother was offering one without a struggle. And Esau had more to say: “Let us journey on our way, and I will go alongside you.” (33:12)

Let’s do this together—you and me.

“You go ahead,” Jacob said. “I’ll catch up.” He watched his brother move off in one direction and, once he was out of sight, Jacob went another. Esau’s blessing was more than Jacob could was willing to receive. Rabbi Rachel Barenblat offers this take on the moment in her poem, “Encounter.”

When Esau saw him he came running.

They embraced and wept, each grateful

to see the profile he knew better than his own.You didn’t need to send gifts, Esau said

but Jacob introduced his wives and children,

his prosperity, and Esau acquiesced.For one impossible moment Jacob reached out.

To see your face, he said, is like seeing

the face of God: brother, it is so good!But when Esau replied, let us journey together

from this day forward as we have never done

and I will proceed at your pace, Jacob demurred.The children are frail, and the flocks:

you go on ahead, he said, and I will follow

but he did not follow.Once Esau headed out toward Seir

Jacob went the other way, to Shechem, where

his sons would slaughter an entire village.And again the possibility

of inhabiting a different kind of story

vanished into the unforgiving air.

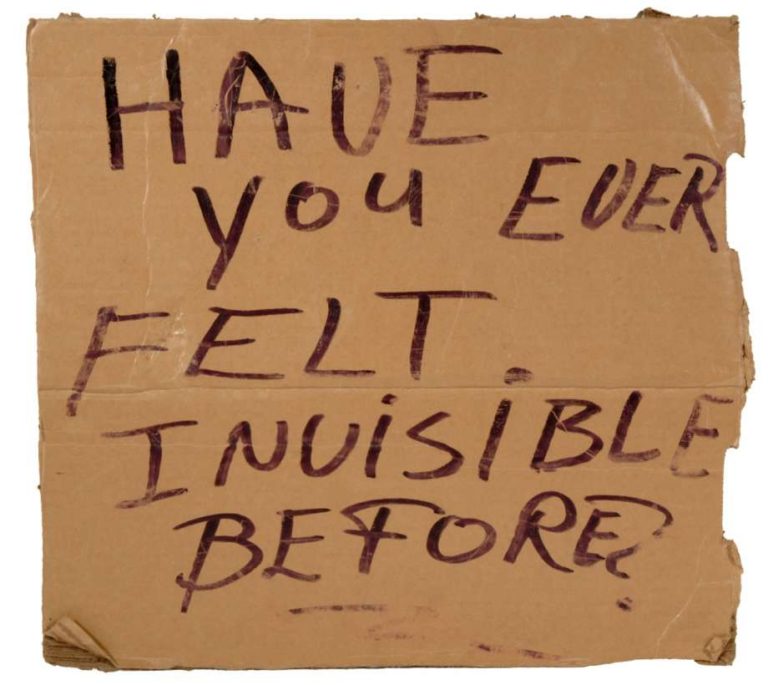

The unforgiving air. What a phrase. It was the only air Jacob knew how to breathe. Whatever had happened the night before, new name or not, when he looked into his brother’s eyes and saw God face to face he couldn’t take it. He didn’t hang on; he let go. It was far easier to see God in the stranger than in the unabashed forgiveness of his brother.

How could he talk it all in? How could he enter a new atmosphere? How could he draw from a new life source?

The companion gospel passage from the lectionary today is what we commonly call the Feeding of the Five Thousand. A multitude of people had followed Jesus out into the desert, hoping for words that mattered, and without much thought, it seems for their personal well being. They were hungry and isolated and there was no food. Even the disciples were convinced it was a suffocating crisis. There was not enough. All Jesus said was, “Feed them.”

They found one boy with a sack lunch of fish and bread. Not enough, for sure. They brought him to Jesus anyway. Jesus blessed the lunch and they started serving. The little boy’s offering changed the atmosphere. People relaxed, ate, shared, and when the had finished there were leftovers. They all breathed in the forgiving air.

My friend Kenny reminded me that years ago Jason Robards was interviewed on Inside the Actor’s Studio and he said, “The actor’s job is to rearrange the molecules in the room.” Another way to say it might be to change the atmosphere. The change the air. Esau tried with his invitation to a new relationship, but Jacob refused. The little boy offered his lunch and everyone ate. Both made small gestures that loomed large.

Our Communion Table is set with small gestures. As people often prone to expect scarcity, perhaps we do ourselves a disservice by setting our table with these tiny morsels of bread and miniature cups. Like the little boy’s lunch, it doesn’t look like much. Our meal hardly qualifies as a tasting, yet the love it represents in overflowing and abundant. When we take and eat, we rearrange the molecules of our lives in Jesus’ name.

The apostle Paul challenges us to set things right with others before we come to the Table: to commit to travel together for the days to come; to fill our lungs with a forgiving air. We can walk away hungry, like Jacob, or we can fill our hearts with our life together in Christ.

The hymn we sang just before the sermon, “O Love That Will Not Let Me Go,” was one of my father’s favorites because of the story behind it. George Matheson was engaged to be married when he found out he was going blind. When he told his fiancé, she broke the engagement. And then he wrote,

O love that will not let me go

I rest my weary soul in thee . . .

It is that love that brings us to this meal together, that fills our hearts and lungs with a forgiving air. Each Sunday morning, my wife Ginger begins our service in Guilford by saying, “Breathe in the breath of God; breathe out the love of God.” Her call to worship is our call to the Table: breathe in the forgiving air of God; breathe out the love that feeds one another, the love that will not let us go.

Come, all is now ready. Amen.