I’ve known this was coming for weeks.

Ash Wednesday marks the beginning of my commitment to write every night during Lent. The mark on my forehead is a harbinger of marks on the page. But I wasn’t sure what I had to say, other than I meant to write more often during Epiphany.

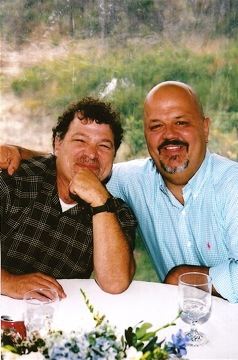

On the train home from New York this evening, I was reading A Time to Live: Seven Tasks of Creative Aging by Robert Raines, who just happens to be a member of our church here in Guilford. The book was a gift from my longtime friend Kenny, which makes the book even better. In a chapter titled “Embracing Sorrow” Bob wrote,

There is an underground river that flows deeper than remorse through the bottomlands of our lives into the valley of sorrow, carrying our tears towards the ocean. And some of us are left with wounds unhealed, loves unrequited, understandings not achieved.

That sentence made me catch my breath.

He went on to talk about his mother dying when he was thirteen and how the “incomplete grieving” of his youth played out later in his life. I finished the rest of the chapter and then looked out the window, overcome with a sadness I could not name other than to say the phrase resonated deep in my heart. I thought about the line in the prayer of confession in the Book of Common Prayer about the “things left undone.” Incomplete. Unfinished.

We had a pretty good snow late Sunday night and it has stayed cold, so the ride along the Connecticut shoreline was particularly beautiful tonight with the snow and the fading light. It felt like the closing scene to something, or perhaps I was reading my sorrow into the grey and amber sunset. I kept looking out the window, wondering what sadness had been stirred up, what work there was still to do. Somewhere in the middle of it, I started thinking about growing up in Africa. Kenya, in particular, which is where I lived in eighth and ninth grade. Bob told about being thirteen when his mom died and coming to terms with his incomplete grief years later.

We lived in a small town called Karen on the outskirts of the city. It was named after Karen Blixen–Isak Dinesen–who wrote Out of Africa. Our house was built on land that had once been a part of her farm. We left Nairobi at the end of my ninth grade year. The plan was to spend a year in Texas on our usual leave and then a year in Accra, Ghana so Dad could work on a special project and then we would be back in Kenya for my senior year in high school at Nairobi International School. When we left for the States we didn’t say goodbye. We thought we were coming back. Six months into our time in Ghana something happened between my parents and the Foreign Mission Board and they resigned. We moved to Houston and Dad was called to pastor at Westbury Baptist Church. I started Westbury High School in January of my junior year not knowing a soul. I did not return to Kenya for another thirty years. And that’s the only time I have been back.

I said goodbye like I knew I wouldn’t be back. Things left undone.

I am aware of how much of my life I have spent trying to find my way home and to create places where people feel at home. I wrote a book about it. It’s underneath why I love to cook for others. I have learned what home feels like in my marriage and in my years in Durham, more than any one place, but the more I think about what feels incomplete it’s less about home than it is in saying goodbye to the person I thought I would become. Growing up in Africa, I imagined I would spend my life somewhere other than America. When we moved to Houston the thought never crossed my mind that I would never live outside of the United States again. That was January 1973. Every address of mine since has had a US zip code, even though I still feel like a third culture kid.

I never said goodbye to the person I thought I would become.

Walt Wilkins sings a song called “Here’s to the Trains I Missed” that offers gratitude for some of what was left undone because of where he ended up.

here’s to the trains I missed, the loves I lost

the bridges I burned the rivers I never crossed

here’s to the call I didn’t hear, the signs I didn’t heed

the roads I couldn’t take the map that I just wouldn’t readit’s a big ole world but I found my way

from the hell and the hurt that led me straight to this

here’s to the trains I missed

I look around at Ginger and the three Schnauzers and I get what he is saying. I live an amazing life full of people who love me. I’ve gotten to do amazing things. And my grief over leaving Kenya remains incomplete. There is still sadness to break forth and more to learn about how the scar tissue of sorrow has hindered my healing, even as I embrace who I have become.

When we were in Durham with a group from our Guilford church a couple of weeks ago, we took them to eat at The Palace International, a Kenyan restaurant with amazing food. I discovered it when we first moved there because they had a sign out front advertising their “world famous” samosas and the picture looked just like the ones I bought from the street vendors in Nairobi after school. And they tasted just like them, too. Whenever my parents came to Durham, we went to eat there and the chef would cook off the menu just for us. Her name is Karen. After our dinner, she came out to meet our group and said, “Welcome home.” There, in one room, were Karen, Nairobi, Durham, Guilford, and me.

Typing that sentence makes me think about a Karla Bonoff song that begins,

though we never know where life will take us

we know it’s just a ride on the wheel . . .

She was singing about the death of a friend, but the chorus feels like what I want to say to the person I thought I would be.

so goodbye my friend

i know i’ll never see you again

but the time together through all the years

will take away these tears

it’s ok now

goodbye my friend

Peace,

Milton