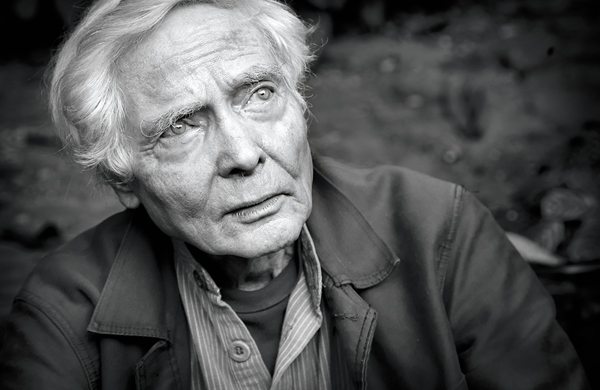

I opened my laptop this evening to the news that W. S. Merwin died yesterday. He was a prolific and powerful poet whose words have left their mark on my life. I am going to use this page to share some of those with you.

My first introduction to him was “For the Anniversary of My Death,” which took on new meaning as I read it today.

Every year without knowing it I have passed the day

When the last fires will wave to me

And the silence will set out

Tireless traveler

Like the beam of a lightless starThen I will no longer

Find myself in life as in a strange garment

Surprised at the earth

And the love of one woman

And the shamelessness of men

As today writing after three days of rain

Hearing the wren sing and the falling cease

And bowing not knowing to what

His poems are full of both grief and gratitude, as you will see in the verses that follow. His words feel simple and rich at the same time. Here is one simply titled “My Friends.”

My friends without shields walk on the target

It is late the windows are breaking

My friends without shoes leave

What they love

Grief moves among them as a fire among

Its bells

My friends without clocks turn

On the dial they turn

They partMy friends with names like gloves set out

Bare handed as they have lived

And nobody knows them

It is they that lay the wreaths at the milestones it is their

Cups that are found at the wells

And are then chained upMy friends without feet sit by the wall

Nodding to the lame orchestra

Brotherhood it says on the decorations

My friend without eyes sits in the rain smiling

With a nest of salt in his handMy friends without fathers or houses hear

Doors opening in the darkness

Whose halls announceBehold the smoke has come home

My friends and I have in common

The present a wax bell in a wax belfry

This message telling of

Metals this

Hunger for the sake of hunger this owl in the heart

And these hands one

For asking one for applauseMy friends with nothing leave it behind

In a box

My friends without keys go out from the jails it is night

They take the same road they miss

Each other they invent the same banner in the dark

They ask their way only of sentries too proud to breatheAt dawn the stars on their flag will vanish

The water will turn up their footprints and the day will rise

Like a monument to my

Friends the forgotten

Here is one I only recently found, though it is not new, called “The Laughing Child.”

When she looked down from the kitchen window

into the back yard and the brown wicker

baby carriage in which she had tucked me

three months old to lie out in the fresh air

of my first January the carriage

was shaking she said and went on shaking

and she saw I was lying there laughing

she told me about it later it was

something that reassured her in a life

in which she had lost everyone she loved

before I was born and she had just begun

to believe that she might be able to

keep me as I lay there in the winter

laughing it was what she was thinking of

later when she told me that I had been

a happy child and she must have kept that

through the gray cloud of all her days and now

out of the horn of dreams of my own life

I wake again into the laughing child

“Yesterday” speaks to the role of a child in another stage of life, as well as the comfort of a friend.

My friend says I was not a good son

you understand

I say yes I understandhe says I did not go

to see my parents very often you know

and I say yes I knoweven when I was living in the same city he says

maybe I would go there once

a month or maybe even less

I say oh yeshe says the last time I went to see my father

I say the last time I saw my fatherhe says the last time I saw my father

he was asking me about my life

how I was making out and he

went into the next room

to get something to give meoh I say

feeling again the cold

of my father’s hand the last time

he says and my father turned

in the doorway and saw me

look at my wristwatch and he

said you know I would like you to stay

and talk with meoh yes I say

but if you are busy he said

I don’t want you to feel that you

have to

just because I’m hereI say nothing

he says my father

said maybe

you have important work you are doing

or maybe you should be seeing

somebody I don’t want to keep youI look out the window

my friend is older than I am

he says and I told my father it was so

and I got up and left him then

you knowthough there was nowhere I had to go

and nothing I had to do

Perhaps the poem of his I come back to the most is “Thanks” because of its tenacious hope and compassionate courage.

Listen

with the night falling we are saying thank you

we are stopping on the bridges to bow from the railings

we are running out of the glass rooms

with our mouths full of food to look at the sky

and say thank you

we are standing by the water thanking it

standing by the windows looking out

in our directionsback from a series of hospitals back from a mugging

after funerals we are saying thank you

after the news of the dead

whether or not we knew them we are saying thank youover telephones we are saying thank you

in doorways and in the backs of cars and in elevators

remembering wars and the police at the door

and the beatings on stairs we are saying thank you

in the banks we are saying thank you

in the faces of the officials and the rich

and of all who will never change

we go on saying thank you thank youwith the animals dying around us

our lost feelings we are saying thank you

with the forests falling faster than the minutes

of our lives we are saying thank you

with the words going out like cells of a brain

with the cities growing over us

we are saying thank you faster and faster

with nobody listening we are saying thank you

we are saying thank you and waving

dark though it is

As I said, gratitude and grief run though his poems. I will close with “Variations on a Theme,” which is about both.

Thank you my life long afternoon

late in this spring that has no age

my window above the river

for the woman you led me to

when it was time at last the words

coming to me out of mid-air

that carried me through the clear day

and come even now to find me

for old friends and echoes of them

those mistakes only I could make

homesickness that guides the plovers

from somewhere they had loved before

they knew they loved it to somewhere

they had loved before they saw it

thank you good body hand and eye

and the places and moments known

only to me revisiting

once more complete just as they are

and the morning stars I have seen

and the dogs who are guiding me

To say thank you for his life and words seems the best thing to do.

Peace,

Milton