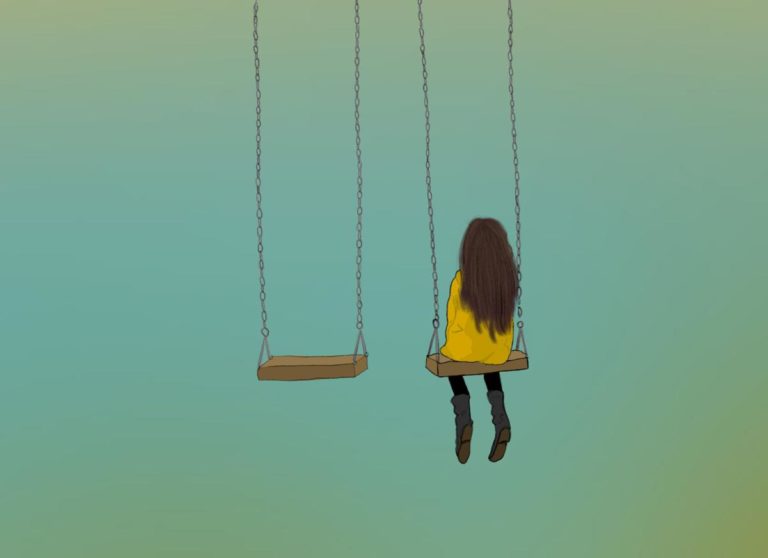

Some days I can deal with the world and some days I struggle.

Tonight is a struggle. Today I read stories about how many states are pushing legislation similar to Florida’s homophobic (in this case, I think we need to redefine homocidal) “don’t say gay” law and another story about Russian troops carrying mobile crematoria into eastern Ukraine to burn evidence of their war crimes before human rights activists can document anything. But the president of France made an angry phone call and most every other Western country keeps trying to figure out how to make sure standing up against Russia doesn’t derail their economies, which means we are doing nothing. Oh, sorry–the US said we would take 100,000 refugees.

And we said it with a straight face.

Years ago, David LaMotte wrote a children’s book called White Flour that told the true story of a group in Knoxville, Tennessee who were trying to figure out how to respond to a Klux Klux Klan march in the city. They dressed as clowns and when the marchers yelled, “White power,” the clowns said, “Oh, we get it! White flour!” and they pulled out bags of flour, ripped them open, and threw them in the air. The Seussian poem goes on with the marchers continuing to yell and the clowns responding with imagination: white flowers, tight showers, wife power until . . .

The men in robes were sullen, they knew they’d been defeated

They yelled a few more times and then they finally retreated

And when they’d gone a kind policeman turned to all the clowns

And offered them an escort through the center of the town

The day was bright and sunny as most May days tend to be

In the hills of Appalachia down in Knoxville, Tennessee

People joined the new parade, the crowd stretched out for miles

The clowns passed out more flowers and made everybody smile

David wrote the book as a way to teach children about ways to respond to violence other than to be violent in return. The last verse says,

And what would be the lesson of that shiny southern day?

Can we understand the message that the clowns sought to convey?

Seems that when you’re fighting hatred, hatred’s not the thing to use!

So here’s to those who march on in their big red floppy shoes

War destroys imagination. Well, first it shrinks our vocabulary and then it destroys our imagination, until we end up sitting in front of a computer, as I am, writing about feeling helpless. The next sentence that comes to mind as I read what I just wrote is:

HELL, NO.

Not necessarily expansive vocabulary, but you get my point. What will it take to think imaginatively about what is happening in our world? Perhaps a better way to ask that question is, who is thinking imaginatively about our world and how can I get in touch with them? How can we all connect?

Ilia Delio says, “If we want a different world, we must be different people.”

One way to read that sentence is to say we must change. The other is to decide to be odd-balls, as in the Southern understanding of the word: well, he’s different.”

I wondered aloud to Ginger tonight what would happen if, instead of refugees fleeing Ukraine, everyone in the bordering countries or whoever could get there would flood the place, inhabit the war zones, and make the Russians kill them too if they were so intent on genocide. I know it’s a long shot, but it seems like it would feel a lot like the clowns in Knoxville, doing something that was an invitation to humanization for everyone involved.

We can’t take the high road as a nation when it comes to war crimes. Pick a war and we have aimed our guns and bombs at civilians. We may not have carried crematoria, but to take a sanctimonious posture at this point is not imaginative. Neither are the sanctions, since too many of the countries involved are still buying Russian fuel. And the financial channels that run through banks and multinational corporations will make sure that the money gets to where it needs to be so everyone can still get richer. Greed doesn’t have much imagination either.

If we want a different world, we must be different people.

My ranting aside (since anger is easier than despair), this post is much less a manifesto than it is a question: How can we imagine a different world? How can we be different in a way that will matter to Ukraine? (Which is not the only place in the world where such atrocities are taking place.)

Seems that when you’re fighting hatred, hatred’s not the thing to use!

So here’s to those who march on in their big red floppy shoes

Where do we find our big red floppy shoes?

Leave your answers in the comments, he said with a smile.

Peace,

Milton