I have been away from much of the media in my life for a few weeks, much of it related to dealing with changes in my life that have taken a toll on me mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. Posting my sermon this week is a way of saying to you and to myself that I want to be more present here. Thanks for sticking with me. The text is Galatians 5:1, 13-25.

______________________________

When I work on my sermon each week, I try to start early.

To give Zoe some time to think about music selections, I select the scripture passage far ahead of time, usually from the Revised Common Lectionary—or at least I try to. On Monday, I look up the passage and read through it and begin to jot down ideas. I read commentaries, other sermons, and then begin the chase the theological rabbits that show up until things begin to come together. If all works well, I hope to have some sort of draft by Thursday or Friday because sermons, like fruit, need some time to ripen.

That didn’t happen this week because the events of the week overwhelmed me and kept changing what I saw in our passage for today. Three things—one public and two more personal to me—kept me grappling with what to say. So here it goes.

The first verse of our passage is puzzling to me because it is so circular: “It is for freedom that Christ has set us free.” It feels a little like the kid who came into class after the bell had rung and the teacher asked, “Why are you late?” The kid answered, “Because I’m not on time.”

What does it mean that we have been set free in Christ for freedom?

And what do we mean by freedom anyway?

Another translation reads, “It is to freedom that you have been called, my brothers [and sisters]. Only be careful that freedom does not become mere opportunity for your lower nature.

Paul then goes on to say freedom is not a license to self-indulgence. To be free does not mean we have the right to do what we want regardless of the consequences or the effect on others. Freedom in Christ is being free to love our neighbor as ourselves. And then he warns, “If, however, you bite and devour one another, take care that you are not consumed by one another.”

I said I had three things that affected what I wanted to say this morning.

The first is that I am leaving my job this week. Thursday is my last day at my job as an editor—a job I have dearly loved. Because I am sixty-five, the verb they use to describe what is happening in that I am retiring, but that is not the whole story.

I did plan to retire from this job, but not for several more years. A change in leadership about a year and a half ago made it apparent that I was not included in the long-range plans for the company—not just me, but a number of my colleagues who have worked there a long time. As I have struggled, a friend said to me, “We either choose our losses or we lose our choices.” I chose to resign rather than stay in a situation that fosters anger, strife, and resentment in my heart.

When I can get beyond my stuff, I can see that my boss is help captive by her woundedness and her ambition. I think she is more miserable than I am. I can’t always get to that place of compassion, but when I do I better understand the kind of freedom Paul describes as the fruit of the Spirit: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control.

I don’t mean that I am just letting this all roll off. I have my exit interview this week and I will speak frankly about the damage that has been done because it needs to be called out. I do mean that I am working hard to want something other than vengeance. I don’t want to respond to her relational violence with violence of my own. I want to be free of it. I don’t want to be remembered for my retaliation. I want to be remembered for my relationships. I don’t want to be consumed by my situation.

That brings me to the second thing—the public thing.

We live in a country where many appear to think that freedom means the right to devour one another. We have seen that again this week. The Supreme Court said it is unlawful to put limits on where people can carry weapons but it is lawful to put restrictions on the choices a woman makes about her healthcare and her body. Emotions run high on both issues, I know. I feel deep sadness and anger that the several of the justices framed their decisions in the context of faith, as though forcing pregnancy and taking away a woman’s right to make choices about her life and her body was the “Christian” thing to do.

Wielding power to make others do what we want them to do is not loving one another as we love ourselves; how can that be the Christian thing to do?

In the contrast Paul sets up in the passage he makes a list of what he calls the works of the flesh. When we read the list, it is easy to focus on the more salacious stuff, but in the middle of it all he mentions “enmities, strife, jealousy, anger, quarrels, dissensions, factions, envy.”

Then he says, “By contrast, the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. There is no law against such things.”

The way we can change the world by living out our faith is not by plotting to gain political power so we can enforce our idea of morality. We change the world by loving our neighbor as ourselves, by choosing to let the Spirit free us from our fears and woundedness and arrogance to be able to live compassionately—to share the pain and grief of those around us rather than adding to it.

Where he listed the works of the flesh, he talks about the fruit of the Spirit. The word translated as fruit carries the connotation of what we give birth to in our lives: what comes into existence as a result of our way of being in the world—and that brings me to my third thing.

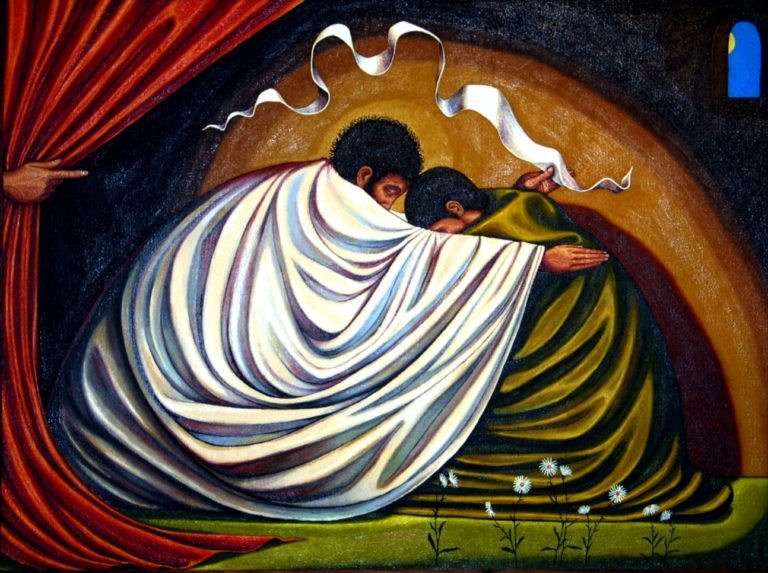

Yesterday Ginger and I participated in a memorial service for our dear friend, Eloise Parks. She and Ginger met their first week of seminary thirty-seven years ago and shared a lifetime together. Eloise died eight months ago. The service yesterday was at Pilgrim Church in Duxbury, Massachusetts where she served as Associate Pastor ten years ago. They reached out to Ginger to say they wanted to do something to mark the impact she had on their lives. We spent a little over an hour yesterday telling stories, singing hymns she loved, and giving thanks for what she gave birth to in our lives. Ten years later, the love they felt from her and for her is vibrant and fresh.

If our words and actions do not foster relationships and do not breed compassion and kindness then we are not free: we are not living as Christ calls us to live. If we are not choosing relationship over doctrine, over partisan allegiance, over fear, over ambition, over self-importance, over however you want to fill in the blank, we are not free: we are not living lives that give birth to love.

“Love your neighbor as you love yourself” is not a requirement; it’s an invitation. In a world that is addicted to divisions and dissentions, we are invited to be free to love.

As Paul said, “Let us not become conceited, competing against one another, envying one another.” And we might add let us not become divided, attacking one another; let us not become self-righteous, imposing our wills on one another; let us not become defensive, projecting our fears on one another.

My siblings in Christ, let us love one another, offering love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. Amen.

Peace,

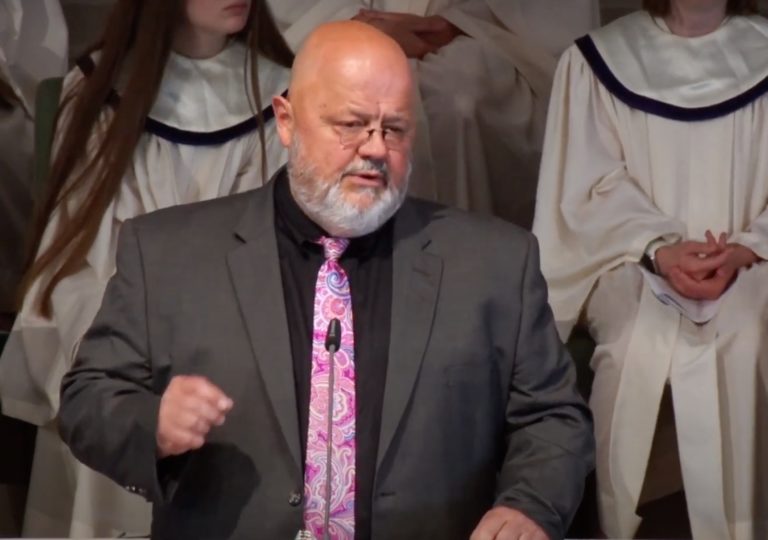

Milton