As Advent began last year, I did not see the gathering dark heading my way. I was preparing for my mother to come for Christmas so she could see our new home in Guilford. We were still unpacking boxes from our move from Durham and she was determined to see our new house. She didn’t want us to live somewhere she had not visited. We picked the travel dates and bought the tickets. Around my birthday, she said she was afraid her health issues were not going to let her travel. We hung on to the tickets and hoped. She went into the hospital on Christmas Day instead of catching a plane, and she died nine days after Epiphany.

For the first time, I begin Advent without a mother and father. So did my brother.

This has been The Year of Few Words, as far as this blog is concerned. Other than my Advent and Lenten disciplines to write daily, my posts have been few and far between. I wrote less than one hundred posts. When I have tried to explain my silence to myself, I point to my grief, or my frustration and exhaustion with our cultural and political climate, or my choice not to add to the noise. Perhaps, now days away from my sixtieth birthday, I am less sure that the world needs to hear what I have to say about most anything than I once was.

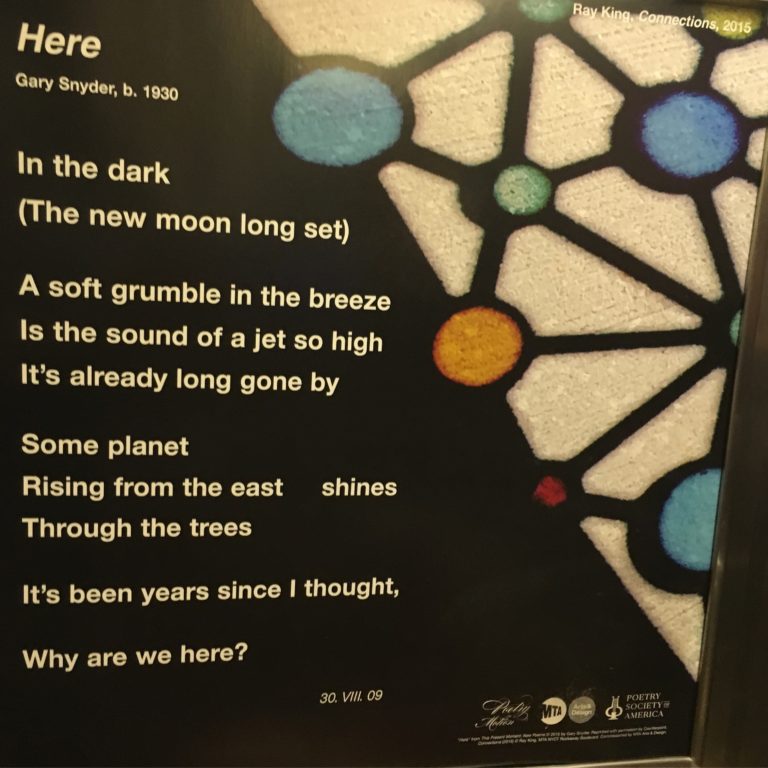

But it is Advent, and I have made a spiritual practice of writing every day during the season. I feel out of practice. The path from my heart to the page is littered and less worn than I want. I need to prepare the way, to clear the path. Some of the cleaning is the daily leaf-blowing kind: cleaning the sidewalks, knowing that the wind will only fill them up again. Some is clear cutting the undergrowth where a path has never been. Some, I continue to learn again and again, is asking for help to find the paths others have cleared and worn, though they are new to me.

The days grow shorter through most of Advent in our hemisphere. In New England the sun appears to just give up around two-thirty or three, taking on the cinematic orange of sunset even though it still hangs fairly high in the sky. By four-thirty, it is gone altogether. By the time it is seven o’clock, I feel as though I’ve been up half the night. The passing of the solstice means the balance turns in favor of the light, but by Christmas the days are not yet longer enough for us to notice. The sun still seems to surrender rather than set. We have to trust the darkness cannot put it out.

I find it helpful that, here in America, the first Sunday in Advent shares a long weekend with a holiday we call Thanksgiving. We end the liturgical year using gratitude as a diving board into the darkness of the new year, waiting for the light in the stable to shine once again. My cup of thankfulness is overflowing because Ginger, my wife, surprised me with my brother, Miller, and my sister-in-law, Ginger. I had asked them to come soon after my mother died and then never heard much about it. Unbeknownst to me, they had colluded to surprise, and it worked.

We had dinner in the barn behind our house in Guilford, a barn we worked hard to restore this past summer. The sextant at church built us a big table out of reclaimed wood he had at his house. While the three of them cleaned and decorated, I cooked, and together we made an indelible memory of family. Driving back from the airport this evening, which is about an hour drive for us, I thought about the stories my brother and I recalled from our childhood and realized I have forgotten more than I have remembered. For all the afternoons we played with our friends in the backyard, there are calendars full of memories that go untouched by our recollection, unheeded, lost under the leaves of time that pile up as one year blows into another. Even the ones I remember are not constant companions, for the most part. I thought of words Paul Bowles wrote in The Sheltering Sky:

past summer. The sextant at church built us a big table out of reclaimed wood he had at his house. While the three of them cleaned and decorated, I cooked, and together we made an indelible memory of family. Driving back from the airport this evening, which is about an hour drive for us, I thought about the stories my brother and I recalled from our childhood and realized I have forgotten more than I have remembered. For all the afternoons we played with our friends in the backyard, there are calendars full of memories that go untouched by our recollection, unheeded, lost under the leaves of time that pile up as one year blows into another. Even the ones I remember are not constant companions, for the most part. I thought of words Paul Bowles wrote in The Sheltering Sky:

Because we do not know when we will die, we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well, and yet everything only happens a certain number of times. How many times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood that is so deeply a part of your being you can’t conceive of your life without it? Perhaps four or five more? Perhaps not even that.

There’s a line in the prayer of confession in the Book of Common Prayer that asks forgiveness “for things done and for things left undone.” I think of my life with my brother and I have to ask forgiveness on both counts. And then I find myself flooded with thanksgiving because in the midst of all that was done and left undone, we found each other in new ways even as we buried our mother. The change came mostly because we chose to give each other the grace we offered others. We reminded ourselves we were together. We were family. After many years, the days we share have begun to grow longer. And, I trust, there is still more light to break forth.

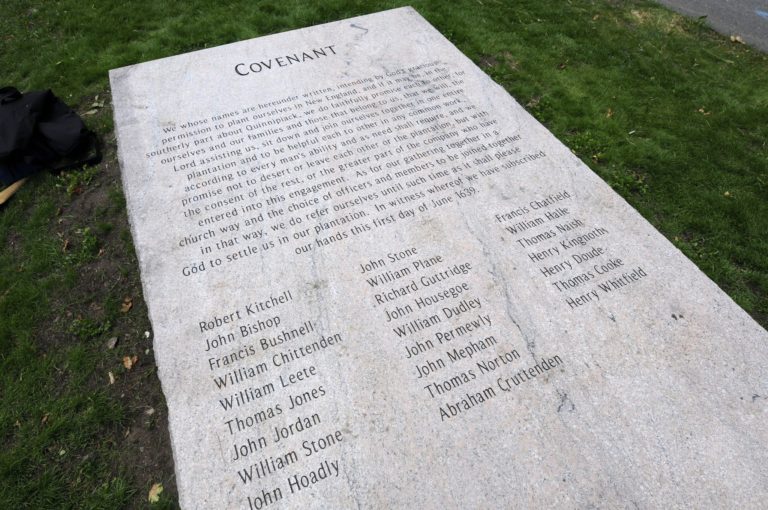

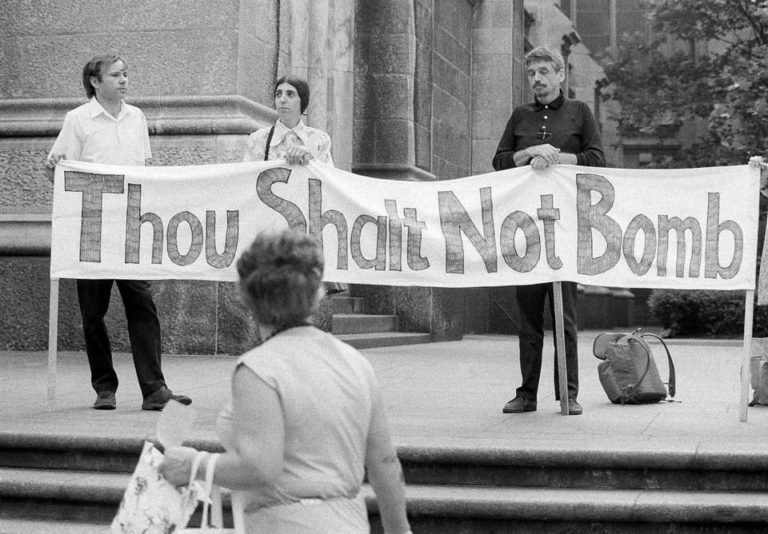

On a larger scale, the darkness this year has been particularly tenacious it seems, and, Christmas or not, it seems poised to go storming into 2017, challenging whatever light we might muster. On one of our walks to show Ginger and Miller our town, we walked past a stone marker that holds the words of the covenant made between the original settlers of Guilford. We read these words:

We whose names are herein written, intending by God’s gracious permission, to plant ourselves in New England, and if it may be in the southerly part, about Quinpisac [Quinnipiac, later named New Haven], we do faithfully promise each for ourselves and families and those that belong to us, that we will, the Lord assisting us, sit down and join ourselves together in one entire plantation and to be helpful to the other in any common work, according to every man’s ability and as need shall require, and we promise not to desert or leave each other on the plantation but with the consent of the rest, or the greater part of the company, who have entered into this engagement.

We are turned to the light when we turn to one another. It is the darkness that divides us, that harbors our fears, that hides the things done and left undone, that leaves us feeling alone. The night is far gone, yes, but I promise not to desert or leave as long as we are in this together. What do you say?

Peace,

Milton