I am going to be preaching several times at the First Church of Christ, Congregational of East Haddam, Connecticut over the next few weeks as they line up an intentional interim and begin looking for a new pastor. It is a lovely congregation. I got to preach there a couple of times last summer. Here is my sermon from this morning, drawing from Numbers 21:4-9 and John 3:14-21.

“Snakes on a Plain”

I must start with a disclaimer this morning: I hate snakes. Everything about them. They scare me.

I grew up in Africa, where my parents were missionaries, and I was deliberately taught to be afraid of and stay away from snakes—and for good reason. Most of the snakes we were around were deadly poisonous. I say all of that because our first reading this morning from Numbers 21 is about snakes. I am happy someone else is reading it. But before she comes to do so, I want to give you a little bit of background. The defining story for the Hebrew people is the Exodus, when God freed them from slavery and led them out of Egypt. But then they spent forty years wandering in the desert of the Sinai peninsula. Moses and his brother Aaron were their leaders. Life was unsettled and transitory. They were still figuring out who they were as a people, since that they were no long defined by their enslavement. Then Aaron died, leaving only Moses. So, yes, the people were whiny about their situation, but they were also grieving. Listen to the story.

From Mount Hor they set out by the way to the Red Sea, to go around the land of Edom; but the people became impatient on the way. The people spoke against God and against Moses, “Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness? For there is no food and no water, and we detest this miserable food.” Then the Lord sent poisonous serpents among the people, and they bit the people, so that many Israelites died. The people came to Moses and said, “We have sinned by speaking against the Lord and against you; pray to the Lord to take away the serpents from us.” So Moses prayed for the people. And the Lord said to Moses, “Make a poisonous serpent, and set it on a pole; and everyone who is bitten shall look at it and live.” So Moses made a serpent of bronze, and put it upon a pole; and whenever a serpent bit someone, that person would look at the serpent of bronze and live. (Numbers 21:4-9)

Our Gospel reading from John 3 is part of Jesus’ encounter with Nicodemus, a Pharisee—a Jewish religious cleric—who came to see Jesus one night to ask questions because he was trying to figure out who Jesus was, and what Jesus was up to. Jesus was doing things that looked like things God would want done, but he didn’t act like the God Nicodemus imagined. In his answer, Jesus referenced the story from Numbers. Listen. Jesus is speaking:

“And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life. For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life. Indeed, God did not send the Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him. Those who believe in him are not condemned; but those who do not believe are condemned already, because they have not believed in the name of the only Son of God. And this is the judgment, that the light has come into the world, and people loved darkness rather than light because their deeds were evil. For all who do evil hate the light and do not come to the light, so that their deeds may not be exposed. But those who do what is true come to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that their deeds have been done in God.” (John 3:14-21)

In the middle of Jesus’ words you heard one of the most well-known Bible verses of all: John 3:16—“For God so loved the world that God sent God’s only son that whoever believes in him will not perish but have eternal life.” But before we go to those words, let’s look at why Jesus talked about snakes to Nicodemus.

Life for the Hebrew people was a mixed bag after they left Egypt. They were no longer enslaved, which was great, but they were nomads. They had no home, no place to go. They lived in the desert, so food was not easy to find. Yes, God sent manna from heaven every morning, but God sent manna from heaven EVERY morning. The menu didn’t change. Life didn’t seem to be changing. Whatever was coming next never seemed to arrive. Then Aaron, one of their two beloved leaders, died. They began to lose hope, even to the point of wondering if God had brought them out of Egypt as some sort of cruel joke. Uncertainty. Difficulty. Failure. Tragedy. Grief. Sound familiar?

And then came the snakes.

God told Moses to make a bronze sculpture of a snake and put it on a tall pole where everyone could see it. If those who were bitten would quit looking at the ground and look up at the bronze snake, they would be healed. They would live.

Jesus and Nicodemus both knew that story. It was at the heart of their Jewish faith. Though Jesus was a long way from being crucified when he talked bout being “lifted up,” by the time John’s gospel was written, the read the words as an allusion to Jesus being “lifted up” on the cross was reasonable, but what kind of cross are we talking about?

God told Moses to make the snake so people could look at it and be healed. If I am lifted up, Jesus said, I will bring healing. The cross is not about punishment, or judgment, or payment of a debt. It is about healing. About life.

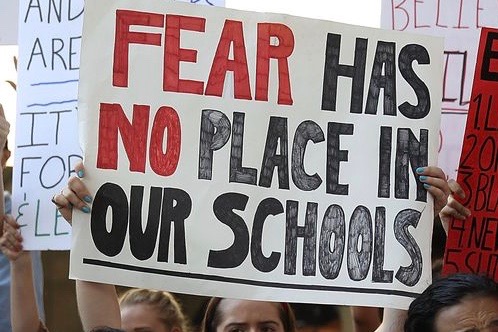

Jesus goes on to talk about judgment, or at least that is how the word has been translated, but the Greek word is krisis. Sound familiar? It is the root of our word crisis—a decisive moment, a turning point. The crisis of the snakes caused the Hebrews to look up at the sculpture, to trust the promise of God’s presence, or to get so mired down in the snakes that they saw nothing but fear and death. God’s love made flesh in the lifting up of the Jesus, the visible sign of God’s grace poured out for the world, creates a crisis, a turning point, a decisive moment for us—a receive God’s redemptive, life changing love. We can get lost in the heaviness of life or we, too, can look to Jesus for hope and healing.

If we took time this morning to name all of the things that burden our hearts, to talk about the pain we live with, to talk about our friends and loved ones who are hurting, to talk about parts of the world that are enduring unimaginable suffering, we would be overwhelmed by sadness. Maybe that’s how you feel today. You hear the story of the snakes and you think, “I know just how they feel.” We aren’t going to tell all our stories out loud, but we can bring them to the Table. We come to the Communion Table together to remember Jesus’ words to his disciples on the night before he was executed.

“This is my body, which is broken for you,” he said to those gathered.

“This is my blood poured out for you,” he told them. “As often as you do this, remember me.”

Remember. There is a centrifugal force to life that pulls us all apart. There is not a person here who is not touched by tragedy or difficulty. If we listen to the news for longer than a few minutes, it looks like our country is coming apart at the seams. We are reminded everyday that life isn’t fair.

And we come to the Table again in this decisive moment to choose to re-member ourselves—to put ourselves back together in Jesus’ name, rather than be bitten by bitterness. We lift Jesus up here at the Table and to find healing once again. If we get to a place where we cannot imagine that God comes bringing love rather than punishment we will get lost in our despair and confusion because all we can see are the snakes on the ground. And so we need to also remind one another that God’s love is the last word. We need to tell the story again: for God so loved the world . . . . Amen.

Peace,

Milton