Guy Clark has a song that says, “Some days you write the song. Some days the song writes you.” Some days that’s true with sermons as well.

_________________________

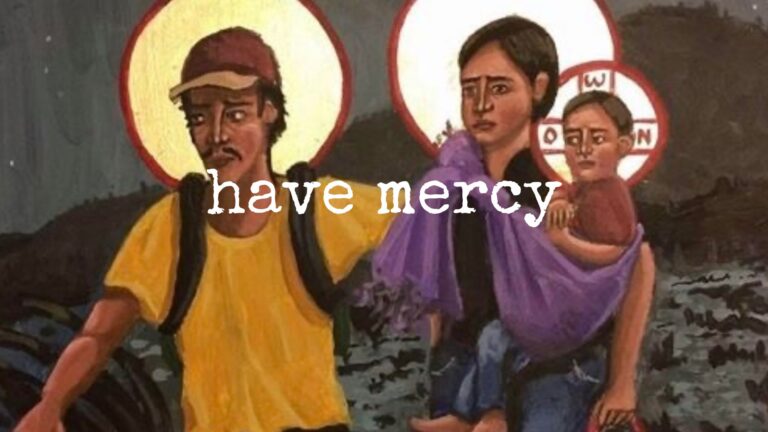

A crowd gathers for worship in a traditional setting. A preacher preaches a sermon, initially embraced by everyone. But then, at the end, the preacher reminds the crowd that the point of that “Good News” is mercy and compassion; not just for them, but also for foreigners. And suddenly the adoring crowd turns. The preacher gets death threats and flees.(from Eric Folkerth)

Some days, reading the from the gospels is like reading a newspaper.

The scene I just described may sound like Washington DC this week, but it is what happened in the passage we just read from Luke 4, which tells the story of Jesus’ return to Nazareth, his hometown. As we noted last Sunday, the scene is tied to both his baptism and his time in the wilderness where he was tempted. But this was not his first sermon. Luke notes that Jesus returned to the region of Galilee “empowered by the Spirit” and went from town to town preaching and healing and had created quite a following.

Then he came back to the town where he had been brought up, where he had been nurtured. Perhaps the synagogue where he spoke was the same one he had attended as a boy. One of those leading the service handed him the scroll from Isaiah. We don’t know if they had their own version of a lectionary or how the scripture was chosen, but Jesus turned to a particular passage and read:

The Spirit of God is upon me, because God has anointed me to preach good news to the poor, to proclaim release to the prisoners and recovery of sight to the blind, to liberate the oppressed, and to proclaim the year of God’s favor.

Then he sat down to talk to them about what he had read, and Luke says those in attendance were fixed on him. He had everyone’s attention. And he said, “Today, you have not only heard the scripture, you have also seen it embodied.”

People were raving about him and were so impressed by his words that they looked at each other and said, “Isn’t this the carpenter’s kid?”

But Jesus wasn’t through. He said, “I know you’re going to tell me to do here what I did in Capernaum, but a prophet is not welcome in their hometown.” And he went on to refer to two stories from the Hebrew Bible that they would have known well—one about Elijah and one about Elisha, both of which involved God’s grace and mercy expanding to include foreigners. The good news he brought was meant for more than the hometown crowd. God’s love knew no boundaries.

And they were enraged because he wasn’t who they expected him to be and they tried to kill him, but Jesus escaped.

If we look back what Luke has said so far, we should not be surprised at who Jesus turned out to be. When Mary was pregnant she sang a song when she visited her cousin Elizabeth, part of which said,

Holy is God’s name. God shows mercy to everyone, from one generation to the next. God has shown strength and has scattered those with arrogant thoughts and proud inclinations. God has pulled the powerful down from their thrones and lifted up the lowly. God has filled the hungry with good things and sent the rich away empty-handed.

When John began baptizing at the Jordan and people wondered if he was the messiah, he said,

“I baptize you with water, but the one who is more powerful than me is coming. I’m not worthy to loosen the strap of his sandals. He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire. The shovel he uses to sift the wheat from the husks is in his hands. He will clean out his threshing area and bring the wheat into his barn. But he will burn the husks with a fire that can’t be put out.”

And then Jesus went from town to town saying he had come to offer mercy, sight, and freedom from oppression, and also to proclaim the year of God’s favor, which was another way of saying the year of Jubilee.

One of the traditions of Hebrew culture was that a Year of Jubilee was supposed to happen when all debts owed to other people were forgiven, all enslaved people were freed, and all land was returned to its original owners. It meant a fresh start for everyone.

Can you imagine what a year of jubilee would feel like? To have all of your debts forgiven? To be freed from exploitive contracts? To get back things that had been lost?

Or maybe we think about what such a year would cost us. Mercy doesn’t come cheap.

When Jesus started talking about extravagant mercy—choosing the disposition to be compassionate and to forgive—the crowd turned on him. To embody compassion in a way that made it available to everyone was too high a price to pay.

I hear the word mercy and I think of a song called “Mercy Now” by Mary Gauthier. The next to the last verse says,

my church and my country could use a little mercy now

as they sink into a poisoned pit it’s going to take forever to climb out

they carry the weight of the faithful who follow them down

I love my church and country, they could use some mercy now

Yes. We could use some mercy now. And as we read these words from Jesus’ first recorded sermon—that set the tone for his entire ministry—we hear again that we are called to be the ones offering mercy to everyone: the people we like and the ones we don’t, those who look like us and those who seem foreign, those we understand and those who confuse or even agitate us, those whom we think belong and those we wish we could exclude.

The word compassion means to suffer together, to carry each other’s pain. Let that definition sink in for a moment: to suffer together, to carry each other’s pain. Too often, our cultural message seems to be “I just want you to hurt like I do.” How then do we live so that we are sharing pain rather than causing it? How do we learn to see the pain around us and then find ways to share the load?

Jesus calls us to see the pain around us and to embody his words with what we say and do:

The Spirit of God is upon me, because God has anointed me to preach good news to the poor, to proclaim release to the prisoners and recovery of sight to the blind, to liberate the oppressed, and to proclaim the year of God’s favor.

As we contemplate what it means to be followers of Christ here in Hamden, here in America, I want to end my sermon by inviting us to read those words together as a pledge of our faith—an embodiment of our understanding of who Christ has called us to be in our time and in this place. The words are printed in your order of service. Let us read them together.

The Spirit of God is upon me, because God has anointed me to preach good news to the poor, to proclaim release to the prisoners and recovery of sight to the blind, to liberate the oppressed, and to proclaim the year of God’s favor.

Amen.

Peace,

Milton