This week’s sermon takes its title from one of my favorite Guy Clark songs, “Come from the Heart,” which I sing as well. The church where I have been interim has some momentous decisions in the weeks and months to come, so the sermon takes a turn towards them at the end. The passage is Mark 1:21-28.

_______________________________

One of my favorite songwriters is Guy Clark. He told stories in his songs that made you feel like he knew your story, too. The first song of his that I ever learned to play and sing—and the song I’ll sing after the sermon—is called “Come From the Heart.” The chorus says,

you’ve got to sing like you don’t need the money

love like you’ll never get hurt

dance like there’s nobody watching

it’s gotta come from the heart if you want it to work

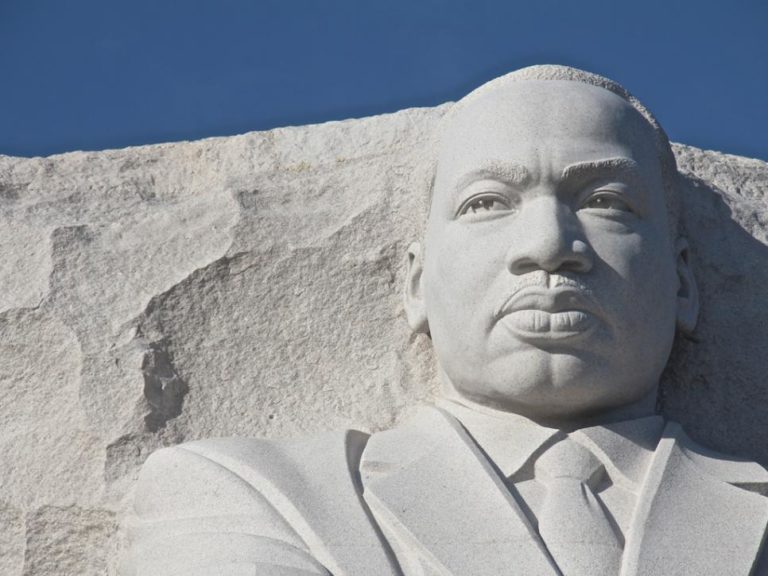

I thought of the song as I read the passage and saw the way people responded when Jesus stood to teach in the synagogue: Mark says they were amazed because he taught with authority, not like the regular teachers. That statement says more about Jesus than it does those who usually spoke. What I hear is that Jesus taught from the heart, and that wasn’t what people were used to hearing.

I remind you, that even though we are through the first month of 2021, we are still in the first chapter of Mark’s Gospel. So far, Mark has covered John the Baptist, Jesus’ baptism, Jesus’ time in the wilderness, John’s arrest, Jesus’ calling his disciples, and now his teaching in the synagogue and healing of a man with as “unclean spirit.” And we still have a few verses to go before we finish chapter 1; next week, we will see Jesus heal a woman who was almost dead. We most often look at these stories one at a time, but it matters to look at the big picture also. Mark is painting with a big brush; he’s not concerned with the particulars. We’ve talked a lot about his missing details—that’s where our sacred imagination comes in.

We don’t know what Jesus said, only how the people responded to it. And in the middle of their astonishment, a man with an “unclean spirit” stood up and said, “What have you to do with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are. You are the holy one from God.”

We don’t really know what Mark meant by “unclean spirit.” The Greek word is used a number of times in the New Testament and it doesn’t always get translated consistently. But the man was troubled or agitated in some way. In the middle of all that was going on, I wonder if those in the room resonated with his first question: “What have you to do with us, Jesus of Nazareth?”

In a way, the troubled man said something that kind of sums up the point Mark has been making in the chapter so far: “I know who you are. You are the holy one of God.”

And in the way that Mark describes Jesus speaking and teaching by heart, he lets us know that Jesus knew it too. But what Jesus knew God intended for his life and what people expected of him were, quite often, not the same thing–which is a big part of the story that unfolds in the rest of Mark and the other gospels, and even in the way we read the stories now.

As we stand alongside of those in the synagogue listening both to Jesus and the anguished man, we are offered a chance to relearn an important lesson of life and faith: often, what first catches our attention may not be at the heart of what is happening.

Most sermons I have heard on this passage never get past the statement that Jesus wasn’t like the regular teachers, as though Jesus’ point was to criticize them. But it’s the people who make that comparison, not Jesus; Mark is saying something larger than this first impression.

When Jesus came into Galillee after John’s arrest–and, perhaps, because of it—Mark recorded what Jesus said. He called people to “change their hearts and minds and trust the good news.” Who knows how long he did that before people started to listen. Last week we also noticed he didn’t magically call Peter, Andrew, James, and John. He built relationships with them that set the stage for them to drop what they were doing and trust the good news. They trusted him.

Though it is the first chapter of his gospel, Mark makes no claim that this was the first time Jesus spoke in the synagogue, only that when he started talking, people started listening in ways they had not. As we said, we don’t know what he talked about, but there was something in the way he said it–like he knew he was telling the truth. Then the man with the unclean spirit stood up and, in a sort of Robin Williams in The Fisher King, seemingly-delusional but spot on profound kind of way, named what was going on. Once again without much detail, Mark just says Jesus cast the unclean spirit out of the man. And once again, the people latched on to something other than what Jesus was really about: “A new teaching with authority!”

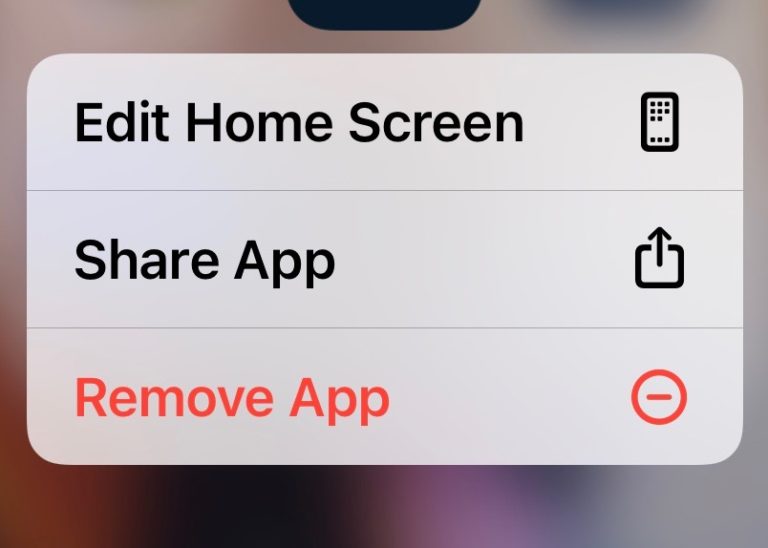

Tucked into the word authority is the word author, and the root of author means “one who causes to grow” or an “originator.” Jesus wasn’t trying to make a name for himself. I think that is why he often told those he healed not to tell anyone. He came, following in the steps of the prophets, to proclaim liberty and hope and love. When Jesus taught, people heard new possibilities in the scriptures, they heard invitations to live in a way that comes from heart–to grow, to risk, to fail, to become. Whatever the regular teachers were saying, it didn’t invite their listeners to that kind of expansive sense of God or themselves that Jesus offered: “Change your hearts and minds and trust the good news.” Can’t you kind of hear Jesus singing,

you’ve got to sing like you don’t need the money

love like you’ll never get hurt

dance like there’s nobody watching

it’s gotta come from the heart if you want it to work

This congregation faces big changes in the weeks to come, alongside of all that is already going on. As we look into that uncertainty, I am reminded of the words of Rebecca Solnit, one of my favorite writers, who says that you need uncertainty to have hope, because it creates the possibility that anything could happen. Hope isn’t the easy road. It’s a little wild-eyed, like the man in the synagogue. Hope is willing to take a step beyond astonishment and ask, “What have you to do with us, Jesus of Nazareth?” and the sit still long enough to hear the answer: “Change your hearts and minds and trust the good news.” We don’t know all that the days ahead will bring. We do know we belong to a God will be with us every step of the way. Amen.

Peace,

Milton