A few years ago, I was speaking at a youth camp and I began by saying, “I basically have one sermon—we are all worthy of love and here to love each other—and I just keep trying to find new ways to say it.” Well, here’s another example. The text was 1 Corinthians 8:1-13.

__________________________

For most of human history people thought the Earth was the center of the universe. We thought the sun revolved around us—well, once we figured out we weren’t on a flat surface. But it has been in my lifetime—and in most of yours—that the reality that we are not the center of things really hit home—at least that is what some cultural historians say.

When the first astronauts went to the moon, they took a picture of our planet from space. It was the first time anyone had been far enough away to have that point of view. As I remember it, one of the astronauts said it was a “big, blue marble.”

We have not been the same since. Our planet was small enough to fit in a camera lens. We weren’t the center of anything other than our lives. It is a truth we still struggle to fully comprehend, to fully engage, and it has a more profound impact on us that just our sense of our place in the solar system.

But the idea that we are not the center of everything is a profoundly personal and human truth as much as it is an astronomical one. And so we move from orbits to idols.

I don’t think the apostle Paul wrote to the Corinthian church about meat sacrificed to idols because it was a huge moral dilemma. Don’t get me wrong: it was a big deal in the congregation, but things that become big conflicts in congregations are quite often small issues.

I heard recently about a church that split—I mean broke apart—over an apple crisp recipe. There was a recipe that had been handed down and used for years. When a new generation of bakers stepped in to carry on the tradition, they wanted to tweak the recipe. Instead, they ended up with two congregations. Over apple crisp.

Like I said, I don’t think the meat was the real issue Paul was addressing, but the meat uncovered the problem. Corinth was a town known for its temples to all sorts of deities, and those deities demanded all sorts of festivals and sacrifices, which, it seems, often meant meat was served.

For many of the church members, being in places where that meat was served didn’t present a problem. The theology was straight forward: We worship the one true God, so those idols aren’t real deities, which means the meat wasn’t really sacrificed to anything and barbeque is barbeque, no matter who cooked it. Let’s eat.

But some in the church had converted from those other sects and religions. They had believed in those idols, and worshipped them. The gears were not as easy to shift. To eat that meat was to fall back into things they had left behind. Some were hurt by those who ate the meat, it seems; some were angered; some felt betrayed or ignored. For some, it was a dangerous invitation.

So Paul said, “Choose people over steaks.” Don’t let the church split over dinner. If you know what you are doing is causing damage to someone else, don’t do it. Your rights are not the most important thing; our relationships are.

Paul, as you can see, was not an American.

As Americans, we were taught early that we have “inalienable rights,” rights that cannot be taken or given away: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. (I love the last one: you have the right to try and be happy.) Over time, that has evolved into a strong sense of individual rights, which far too often is interpreted to mean something like, “I have the right to do what I want,” which is not an untrue statement, necessarily, but it is an incomplete one. Life is rarely, if ever, about just me.

As you have heard me say more than once, life and faith are team sports. How we play nicely together has to do with how we pay attention to the impact of our words and actions, regardless of our intent, or what we think we have the right to do.

In the scenario described in our scripture passage today, those who ate the meat didn’t think it was a big deal. They assumed that if it wasn’t a big deal to them, then it wasn’t a big deal, period. Paul questioned their logic, reminding them that their perspectives weren’t the center of everything. He wasn’t saying they weren’t free to eat the meat, he was asking them to consider more than just the menu. They were also free to choose not to eat the meat and strengthen the relationships within the congregation.

Why not, then, choose the option that frees someone else as well?

When we lived in Durham, North Carolina one of my favorite places to meet people to talk or hang out was Fullsteam Brewery, which was in walking distance of our house. The people that owned it created an atmosphere of belonging that just made me want to be in the room. One of my good friends there was in recovery. We got together often to talk and work on creative projects together, but when I met with her I did it at a coffee shop nearby. I chose supporting her recovery over hanging out in my favorite gathering place.

But then you get to the apple crisp and it’s a different kind of digging in. That church didn’t split because the recipe wasn’t a big deal; it was, to both sides. Now I am choosy about my apple pie (I prefer pie over crisp myself), but whatever was going on in that church was not really about apples. Truth is most every congregation has stories—maybe not as dramatic as this one—about people who have left the church because of something where people got dug in and it became a power struggle. Folks made being right or being in charge or being whatever they thought they had to be over choosing each other.

And that is what it boils down to: choosing each other.

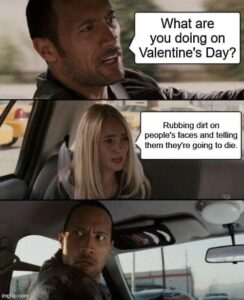

Many years ago, I heard a work colleague trashing Valentine’s Day because, he said, “it was a Hallmark holiday made up to get us to spend money on flowers and chocolate.” He didn’t say it to start an argument, but I felt the need to respond. What I said was, “I don’t know that I need to defend Hallmark, but I figure any chance I have to let Ginger know I love her is worth taking, so happy Valentine’s Day.”

Whatever the issue, whether it’s the apple crisp, or how things are stored in the kitchen, or what color we paint the trim, or whatever might come up that we find ourselves feeling either entitled to do or somehow desperate to hang to, why not choose, instead, to find a way to say, “You matter more to me than how we clean the coffee pot.”

Life is not a battle, or even a series of skirmishes, unless we make it so.

Why not take the chance to say, “I love you,” in a tangible way?

Whether we are talking about life together here at church, or in marriages, or families, or friendships—whatever the relationship is—may we remember we are not the center of the universe. It is more important to be right, or to be first, or to be able to do whatever we think we have the right to do. So Paul wrote, “Sometimes our humble hearts can help us more than our proud minds.”

A few paragraphs later in his letter to Corinth that Paul wrote words that are more well-known:

Love is patient; love is kind; love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. Love does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable; it keeps no record of wrongs; it does not rejoice in wrongdoing but rejoices in the truth. Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. Love never ends.

Let us love one another every chance we get. Amen.