This week’s passage was the story of Moses and the burning bush, which set me thinking about the little fires that ought to catch our attention.

______________________

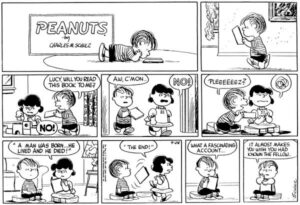

Reading the account of Moses’ life as it is told in the first three chapters of the Book of Exodus reminded me of a Peanuts cartoon where Linus goes to his sister Lucy and implores her to read a book to him. She refuses not once, but twice, and then, after he says, “Pleeeeez!” she acts as if she is reading and says, “A man was born . . . he lived, and he died. The end!”

As she storms off, Linus says, “What a fascinating account. It almost makes you wish you had known the fellow.”

Our story might be a little longer than the eight panels of a Peanuts cartoon, however, the writer of Exodus moves quickly from Moses’ birth, to Miriam, his mother, saving his life by hiding him in a basket in plain sight so he would be taken and raised in the Egyptian court, and then, as a grown man, having to flee the court because he killed an Egyptian who was abusing an enslaved Hebrew man. The story moves quickly. Moses fled from Egypt to the land of Midian, which is part of Saudi Arabia—about 300 miles away—where he found work, and then found a woman who became his wife. They had children. Moses became a shepherd for his father-in-law, Laban. The Pharoah from whom Moses had fled finally died. The Hebrew people remained in slavery.

We have no real measure of how much time all of that took, other than a lot more must of have happened to Moses than the two or three things that are written down here. We, like Linus, almost wish we could have known the fellow.

As I read through the story this week, I became more aware of how far away Moses was from Egypt—the land where he was born and raised—than I had been before. When Moses fled, he ran (or walked) a long way. He didn’t go to Canaan, where his ancestors had settled. He crossed the Sinai Peninsula and ended up in Midian. He put a great deal of distance between his old life and himself. He does not appear to have spent much time thinking about the plight of those he left behind.

And then, one afternoon, he came upon a bush, there at the edge of the desert, that was burning but not burning up, and it caught his attention. As he tried to figure out what was going on, God spoke to him from the flames and called him by name. When Moses answered, God told him to take off his shoes as a sign of reverence. Then God started talking about the plight of the Hebrew people and how God was going to send Moses to lead their liberation.

Moses responded with the first of two questions: “Who am I to go and do that?”—another way of saying, “What’s that got to do with me?” or “Who am I?”

God answered with the promise of presence, to which Moses responded with his second question: “What do I say if they ask what your name is?”—another way of saying, “Who are you?”

The reply makes God sound a little like the old cartoon some may remember, Popeye the Sailor Man: “I am who I am,” but then God expands the answer:

“Go and get Israel’s elders together and say to them, ‘The God of your ancestors, the God of Abraham, of Isaac, and of Jacob, has appeared to me and said, “I’ve been paying close attention to you and to what has been done to you in Egypt. I’ve decided to take you away from the harassment in Egypt to the land of the Canaanites . . . a land full of milk and honey.”’

Did you hear it? God said, “Tell them, ‘I’ve been paying close attention to you . . .’”

God caught Moses’ attention with the burning bush in order to call him to pay attention to those whom he had forgotten. Moses had fled Egypt in fear for his life, and then, over time, the distance of miles and years turned the fear into indifference. He wasn’t consciously working to avoid those whom he had left in Egypt, he had just gotten used to not thinking of them.

God broke into his consciousness with the burning bush and then redirected his attention.

The Elizabeth Barrett Browning quote on the cover of our order of service fits well right here:

Earth’s crammed with heaven, and every common bush afire with God, but only those who see take off their shoes; the rest sit round and pluck blackberries.

It is tempting to hear her words and assume we are among the shoeless rather than the clueless, but perhaps this is a moment when we need to pay attention to what is burning in our hearts. Who needs our attention? Who are we passing by?

One of the newsletters that I read regularly is called The Art of Noticing. It is written by a man named Rob Walker. Each issue talks about ways to notice life around us, to pay attention. In one of his articles he said, “Pay attention to what you care about, and care about what you pay attention to.”

I had to sit with the circularity of that one for a minute—“Pay attention to what you care about, and care about what you pay attention to.”—but then he pointed to a friend’s writing that expanded on the idea: we don’t pay attention (or care) for people because we love them, we love them because we pay attention to them.”

Attention leads to love, not the other way around.

We have to pay attention if we want to see all the little fires that burn with the presence of God; otherwise, we will just continue living our busy lives. The burning bushes in our lives may not call us to something as monumental as leading the Hebrew people out of slavery, but they will lead us to love.

Earth is crammed full of the presence of God, whether we are standing in our gardens, or surrounded by loved ones, or in line at the DMV. Every face that looks back at us in coffee shops and grocery lines is filled with the image of God. Should we choose to notice—to pay attention—we give ourselves the chance to love someone. Ginger and I were talking about this idea and she recalled something that happened to me in Harvard Square one day.

I passed a man who was sitting on the sidewalk holding a paper cup. He asked for some change. I was going into the coffee shop behind him, so I said, “I’d be happy to get you a coffee and a muffin.”

He paused for a moment and said, “A Coke and a brownie?”

I thought, “Why not? Ginger would want the same thing,” and told him I would be back. When I got inside the coffee shop, the brownies looked amazing, so I got two. When I gave him his food, I sat down next to him on the curb and we shared our meal.

It’s a good story. I wish I had more like that—and not only about strangers, but also of people I know well. It’s worth asking ourselves how well do we attend to those nearest to us: family, friends, people at coffee hour, people at work? If paying attention grows our love for others, what are we doing to deepen our love for one another?

How are we as a church paying attention to our neighbors? What is happening around us that we are seeing? What are we missing? How can we pay better attention so that we have a chance to learn to love those nearby?

Hamden is crammed full of heaven, every corner ablaze with the glory of God. May we be those who pay attention to the sacredness all around us. Amen.

Peace,

Milton

Your sermons are wonderful and always so thought provoking. Thank you for sharing them.