One of the surprises of our Ireland trip for me was to learn that C.S. Lewis was born in Belfast and grew up there. I realized my knowledge of him was as a professor in England and I had never considered an Irish connection. The City of Belfast created the square,  which has a beautiful open area, a whole bunch of trees and other plants, and several metal sculptures of characters from the books, as a part of a wider urban regeneration project designed to help East Belfast, an area that has struggled economically and one that also bore the brunt of a good bit of violence during the Troubles.

which has a beautiful open area, a whole bunch of trees and other plants, and several metal sculptures of characters from the books, as a part of a wider urban regeneration project designed to help East Belfast, an area that has struggled economically and one that also bore the brunt of a good bit of violence during the Troubles.

As I wandered around the square (and took my picture with Aslan), I couldn’t help but go back to my favorite conversation in the stories–one I wrote about in my book–where Lucy, the youngest of the children, encounters Aslan on a return visit to Narnia. She runs to meet him.

“Aslan, Aslan. Dear Aslan,” sobbed Lucy. “At last.”

The great beast rolled over on his side so that Lucy fell, half sitting and half lying between his front paws. He bent forward and just touched her nose with his tongue. His warm breath came all round her. She gazed up into the large wise face.

“Welcome, child,” he said.

“Aslan,” said Lucy, “you’re bigger.”

“That is because you are older, little one,” answered he.

“Not because you are?”

“I am not. But every year you grow, you will find me bigger.”

Right before we moved on to our next place, several of us went into the coffee shop that sits on the square and I saw another of my favorite quotes in a tryptic on the wall:

“It’s not as if he were a tame lion.”

One other rather random memory that came back as a stood in CS Lewis Square is from our trip to Turkey for Ginger’s first sabbatical. We were in Istanbul and two Turkish teams were playing football on the television where we were. One of the teams was called Aslan. I asked someone about the name and they told me aslan is the Turkish word for lion. I have always wondered how Lewis made that connection.

This morning, I continued my slow journey through Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass and was taken back to that morning in Belfast with Aslan by one sentence:

I’ve noticed that once some folks attach a scientific label to a being, they stop exploring who it is. (208)

She was talking about the way scientists think about plants, and the way in which some can become accustomed to taking their presuppositions as truth–as though a name and a label were the same thing. She continued,

Most people don’t know the names of these relatives; in fact, they hardly even see them. Names are the way we humans build relationship, not only with each other but  with the living world.

with the living world.

In the margin I wrote, “True of theology.”

One of the terms I have never understood is systematic theology. Kimmerer seemed to be describing those who were captivated by the idea of systematic botany. I don’t think either one works. As Tom my garden buddy says, “Nature doesn’t grow in rows.”

Labels have their value when they are on canned goods and prescription bottles, but they fall apart quickly when it comes to faith and relationship.

Another article I read today talked about how the chapter divisions and headings in our Bibles often keep us from seeing the larger picture. I thought of the parable we call “The Prodigal Son,” which is a story that has so much more going on than the misadventures of a wayward young man. The label tames the story instead of setting it free in our imaginations to see the nuances of family dynamics, the grief that shoots through everything, and the reckless nature of forgiveness.

I think that connection is what sent me back to Belfast. Any account of the Troubles seems to involve labels–Catholics and Protestants, Republicans and Unionists, Nationalists and Loyalists–that were both chosen and inflicted. Any definition of one of the terms is crippled by brevity: a Republican wants a united Ireland; a Unionist wants to stay with Britain, for example.

Labels create the illusion of a name.

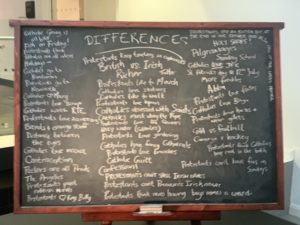

We visited the Ulster Museum later in the day and, thanks to the direction of a very helpful docent, were led into an exhibit that showed the seeds of the Troubles going all the way back to ships in the Spanish Armada that sank off the coast of Ireland centuries before there was a Belfast. Towards the end of the exhibit was a blackboard from an episode of  Derry Girls where Catholic and Protestant students tried to describe what they had in common. The lesson devolved into a cacophony of differences because they had no idea how to explore beyond their labels.

Derry Girls where Catholic and Protestant students tried to describe what they had in common. The lesson devolved into a cacophony of differences because they had no idea how to explore beyond their labels.

What is true of Aslan as a metaphor for God is true of us, who are created in God’s image: it’s not as if we are tame. Labels are a way of domesticating one another–please fit in this box and make my life easier; allow me to make you one-dimensional so you will fit in my system of good and evil, or whatever binary I have created to let me think I understand the world.

On an earlier page, Kimmerer said, “We learn from the world how to be human.”

Not to be tamed, but to be human–literally “earthly being,” actually made of stardust, the same material as all of our untamed universe. Instead of systems, we are better off telling stories, like Narnia, or the parables, or the one about why we are friends, or how I feel about my family now that my parents have been dead for years that I didn’t see before.

Good stories are expansive. When we hear them and tell them we grow and everyone–every being–around us gets bigger, like Aslan, which is not always a comforting thought but then, growth is not necessarily comfortable or painless. Aslan was a lion, after all.

I have deleted a couple of sentences because I felt like I was gett ing preachy and that’s not where I wanted this to go, so I’ll go back to imagining little Jack Lewis playing in the streets of Belfast long before the urban regeneration project was even a dream. I wonder he saw on those streets planted the seeds of Narnia, where he learned the Turkish word for lion, and how he managed to become an adult who could still tell fairy tales, just as I wish I knew more about how Jesus grew up and how he learned to talk in parables, which aren’t that different from fairy tales. They are both untamed stories.

ing preachy and that’s not where I wanted this to go, so I’ll go back to imagining little Jack Lewis playing in the streets of Belfast long before the urban regeneration project was even a dream. I wonder he saw on those streets planted the seeds of Narnia, where he learned the Turkish word for lion, and how he managed to become an adult who could still tell fairy tales, just as I wish I knew more about how Jesus grew up and how he learned to talk in parables, which aren’t that different from fairy tales. They are both untamed stories.

Peace,

Milton

Readable, comforting, thoughtful, so glad this blog was recommended to me (by Karol Daniel).

Another gem! Thank you, Milton.