For many years I have written daily during Advent. For the first time in a long time I will be preaching through Advent as well. My sermon for this first Sunday is “We Will Get Through This,” drawing from Isaiah 64:1-9.

______________________________

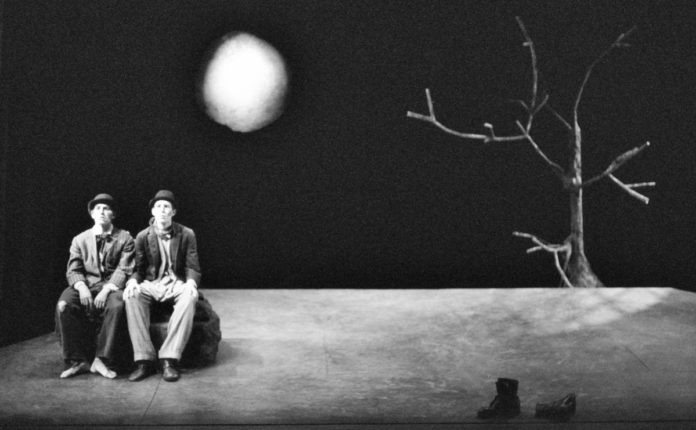

Somehow it is the first Sunday in Advent and we are on the cusp of December. I know we all find some solace in knowing that 2020 only has one more month left, and yet it is hard to find much indication that 2021 is going to give us much of a respite—at least it feels that way to me. It takes me back to my high school drama class and Samuel Beckett’s play, Waiting for Godot, which is a play about two men, Vladimir and Estragon, who are waiting for someone who never shows up. At one point, Vladimir says, “I can’t go on like this,” and Estragon replies, “That’s what you think.”

We are going on. Day by day.

I don’t know how it felt at your house, but Thanksgiving was a mixed meal of gratitude and grief at ours. For one thing, my cousin (I only have two) is in the ICU in Houston with COVID pneumonia. Like many of you, we were also distanced from loved ones who are usually around our table. That said, we had a good day even as we were aware and even talked about all we have missed or lost this year, and how we now get to look forward to a Christmas that may be much the same.

I have spent the last nine months trying to remember what day of the week it is as though time was sort of standing still, on the one hand, and then being caught by surprise by how quickly the months have passed on the other.

Since I’ve already started talking about theater, I’ll keep going. One of my favorite musicals is Fiddler on the Roof. In the scene where the Jewish villagers are being evicted by the Russian Cossacks from Anatevka, the town that had been their home for generations, one of them turns to the rabbi and says, “Wouldn’t this be a good time for the messiah to come?”

Yes. Yes, it would.

It is fitting then, for us to begin Advent, our season of waiting for Christ to be born again in our time and in our circumstance, with a prayer of lament from Isaiah. These words came towards the end of the Hebrew people being exiled—being prisoners of war—in Babylon for seventy years. I think of what it has been like to feel isolated for nine months—how disorienting and depressing and disruptive it has been—and I can’t imagine how people stayed hopeful when it went on for generations.

Isaiah starts his prayer begging for divine intervention: why don’t you just tear open the heavens and come down here in the middle of everybody and show them Who’s Who? Do one of those big God-like things you used to do when you sent floods and fires and all the other big special effects into the lives of our ancestors. No one had ever seen anything like it—and you did it because they were your people. They trusted you because they knew you would come through.

It’s that last line that tips the prophet’s hand and shows his insecurity. The stories that had been handed down were told in a way that said God did big things for us because God loves us. When things get tough, it gets easy to think, well, if God isn’t doing big things now does that mean God doesn’t love us as much anymore?

Where is God in the middle of our isolation anyway? How do we find God when we feel abandoned?

As he continues to pray, Isaiah answers his own question by swinging back and forth between saying, “It’s because we keep sinning, isn’t it?” and “No one expects you to show up because you’ve been gone so long.” I love the honesty in his words. He talks to God as if God can take it.

And then he seems to go pretty hard at God: “We are just clay, and You are the potter.

We are the product of Your creative action, shaped and formed into something of worth,” as if to say, we are worth something because you made us.

I wonder who he was trying to convince—God or himself.

What does it mean to pray in these days? Rabbi Jonathan Sacks says,

There are simply too many cases of prayers being answered for us to deny that it makes a difference to our fate. It does. I once heard the following story. A man in a Nazi concentration camp lost the will to live – and in the death camps, if you lost the will to live, you died. That night he poured out his heart in prayer. The next morning, he was transferred to work in the camp kitchen. There he was able, when the guards were not looking, to steal some potato peelings. It was these peelings that kept him alive. I heard this story from his son.

Perhaps each of us has some such story. In times of crisis we cry out from the depths of our soul, and something happens. Sometimes we only realize it later, looking back. Prayer makes a difference to the world–but how it does so is mysterious.

I was getting ready to record the worship service for this week when my phone rang. It was my cousin calling from an ICU in Houston with COVID pneumonia. She has been there for most of the week; she is improving, but, as she said, she is not out of the woods. She had called earlier in the day, which was the first time I had heard her voice in almost a week. She was short of breath and couldn’t talk long. When the phone rang the second time, she said, “Will you read me a story? Not something sad. You know, something once upon a time.”

I was sitting at my laptop, so I typed in once upon a time, and then children’s stories, until I stumbled upon Peter Rabbit. So I read Peter Rabbit to her. It felt as insignificant as those potato peelings, yet when I finished she said, “Thanks for helping me not feel alone.” I didn’t make her better. She is still in ICU. But it was a way to say, “I love you.”

In our own way, my cousin and I played our own version of Vladimir and Estragon’s brief exchange:

“I can’t get through this.”

“That’s what you think.”

Getting through things is kind of what it means to be human. Getting through things is what hope is all about, I think, because the choice we have, almost daily, is how we will get through it. We can get through by blaming others, or God, for our circumstances. We can get through by lashing out at those around us, or those who disagree with us. Or we can get through by realizing we are all in this together, even when we have to live at a physical distance. We can get through it trusting that nothing can separate us from the love of God, even when we don’t feel a sense of God’s presence.

Several years ago I stood with a friend at his father’s graveside service and heard an elderly country preacher read Paul’s words from Romans with a Southern lilt—which I will not try to imitate. “Shall anything separate us from the love of God? “NO,” he said with such confidence and conviction standing over that coffin that I have not read or heard those words the same way since.

Our season of Advent is one of the ways we say, “Wouldn’t this be a good time for the messiah to come?” Meister Eckhart, a thirteenth century mystic sort of reframed the question in a way that calls us into the middle of it all, “What good is it to me for Mary to give birth to God’s son if I do not also give birth to him in my time and my culture?”

When Joseph laid in bed wondering how he was going to get through Mary’s pregnancy, the angel told him the messiah was coming and to name the child Emmanuel: God with us—with being the operative word.

God is with us. Nothing can separate us. We will get through this and whatever comes after this by telling stories of potato peelings and Peter Rabbit and a pregnant Judean teenager to remind us our story is not yet over.

We will get through this. That is what I think. Amen.

Peace,

Milton

Bread of Heaven for earth as it is.

Bothe comforting and inspiring. Thank you, Milton.