Palm Sunday is a day full of contradictions to me, particularly in the way we observe it as Jesus’ triumphal entry, because I don’t think triumph was a central word in Jesus’ vocabulary. As I read the story again this year, preparing to preach, I saw something I had not seen before, and that was the connection of his ride into town with the parable he told just before he climbed on the colt. Here’s my sermon.

_________________________________

Did you notice the way our passage began this morning?

After he had said all this . . .

Once again, we are picking up in the middle of the story and trying to figure out what is going on. Let me give you a quick rundown.

For the better part of six chapters, Jesus has been telling parables to describe how God works in the world and, correspondingly, how God is calling us to do the same. Along the way, a couple of healing stories are thrown in. The beginning of the chapter we read this morning–Luke 19–starts with Jesus’ encounter with Zacchaeus, the tax collector who climbed a tree to see Jesus and then Jesus not only talked to him but invited himself to dinner at Zacchaeus’ house. Then Luke moves to another parable about a rich man who was leaving to go take control of another country (that didn’t want him to take control, but he was going to anyway). He called three of his servants and put each of them in charge of some money: one got ten minas (one mina was about three months wages, so two and a half years of salary), one got five minas, and one got one. He didn’t give them the money as a gift; he wanted them to keep his business going while he tried to pull of his hostile takeover. He also didn’t give much in the way of instruction other than to continue doing business with what they had. When he returned–after successfully forcing himself into power in the other country–he called them in to give account for their work.

The one with ten made ten more, and the master rewarded him by giving him more responsibility, though I’m not sure it was much of a reward. The one with five made five, and was also rewarded in the same manner. The one who was given the least amount, a single mina, returned it telling his master that he was scared of losing the money so he just hid it so he could return in unscathed. The rich man took his mina and gave it to the one who had ten and then said he wanted the people who had fought against him in the other country brought in and executed in front of him.

And after Jesus finished that uplifting parable—without explaining it–he told his disciples to go into town (which was Bethany where he had raised Lazarus from the dead and where Mary had poured perfume on his feet) and get the colt they would find tied to a tree, which they did. Then they put their cloaks on the back of the colt and helped Jesus up on its back and they began the trek down through the Kidron Valley to the gates of Jerusalem, about a mile and three quarters.

Did you get that? Jesus’ ride didn’t take place in the city of Jerusalem. I have missed that detail before now. He was still outside the walls.

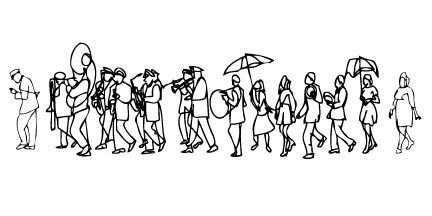

The road from Bethany to Jerusalem winds down from the Mount of Olives past the Garden of Gethsemane and then winds through a cemetery–an ancient burial ground that predated Jesus, which means the people who lined the path to see him were standing in a graveyard waving branches throwing their cloaks in front of him. It was more akin to a New Orleans jazz funeral than a triumphant parade.

With that image in mind, Iet’s go back to the parable Jesus told before he got on the horse.

As Jesus was preparing to go into Jerusalem for what he was pretty sure was the last time because the unwanted oppressive Roman government had grown weary of his impact, he told a parable about an unwanted ruler who was only concerned with getting more for himself.

I know–to our American ears, so trained to listen for anything that supports the Protestant Work Ethic and the American Dream, it’s easy to hear this as a story about how hard work pays off. But it doesn’t. Not in this story. The rich man gave the servants money to invest for him, not for themselves. They were running his business, not profit sharing. He didn’t give the mina from the man who had hidden it to the one who had doubled his ten as a reward; he gave it to him because he was better at making money. And he didn’t punish the servant who just held on to the money, or at least not in the parable. He hears about his investments and then decides he wants to see the people who resisted his takeover executed right in front of him. This was a wicked, evil, mean, and nasty man.

He is not a symbol for God in the parable, and we are not the servants in this story. Everyone in the parable loses at the hands of the unwelcome and unjust ruler who found a way to crush everyone.

And after this parable about the damage of unbridled greed and power, Jesus got on a colt to ride to Jerusalem–but not because he thought he was going to be the conqueror.

The ride down through the cemetery and into Jerusalem was not triumphant. We have named it that because we, like many of those lining his path, keep hoping God is going to start making things go our way so we can be the ones in power, but Jesus knew better. He knew he was going to lose, just like everyone in the parable did, and he went anyway.

He knew that triumph and power would not have the last word. When some around him said he ought to tell his followers to keep it down with the hosannas, perhaps another way of saying, “Pipe down or you’re going to get in trouble,” Jesus said, if the people quit singing the rocks will cry out, which is another way of saying love is the last and strongest word–but not just in a “someday” sense.

One of the sayings I love is “Love wins in the end; if love hasn’t won yet, it’s not the end.” I trust that is true, but I also think love is not something we have to wait for. In the past few decades, we have learned a great deal about the universe that we are a part of. We’ve learned that trees talk to each other and feed and care for each other, sometimes over great distances. Scientists have found forests are best seen as one large organism rather than a bunch of individual trees. They share nutrients, support those who are sick; they take care of each other.

Instead of thinking matter is made of particles, scientists have learned that everything is made of energy–of spirit if you will. And again, they are finding that everything is connected. Relationship is the foundational building block of the universe at every level. Like the forests, we are one big organism built to take care of one another. Some scientists and theologians even say it this way: love is the fundamental force in the cosmos. Hold that thought for a moment and listen to the words of Paul:

Love is patient; love is kind; love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice in wrongdoing, but rejoices in the truth. It bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. Love never ends.

This morning as we gather, Russia is still mercilessly attacking Ukraine–and that is not the only spot in the world where people are being brutalized by power and wealth, its’ just the one we have chosen to notice. Our country is a war zone of its own. We have become incapable of most any kind of compassionate communication. We are broken, but we keep acting like we’re not, as though that will somehow make it okay. To say we have much in common with those waving branches in the graveyard is an understatement.

The trajectory of the week ahead as we follow Jesus into Jerusalem means this sermon doesn’t have a happy ending. Jesus is going to die. The men around him will all run away. The women will stay. And all of them will lose, just like the folks in the parable. As I have said a couple of times this Lenten season, resurrection requires death. We are not marking a triumphal entry today, we are a part of a funeral procession, and–not but–if we listen close, we can hear the rocks are singing and the trees talking and the cosmos humming because

Love is patient; love is kind; love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice in wrongdoing, but rejoices in the truth. It bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. Love never ends.

One more time: Love never ends. Amen.

damn! you’re good!

Thank you, Milton. I still have hope and your words ring true for me.

I’ve listened to these stories every year for well over half a century and you always seem to give me a new way to hear and consider them. Thank you, Milton.