I had some time to read on my lunch hour today, so bell hooks was once again my companion. The essays in her book, belonging: a culture of place, have been challenging, encouraging, and disquieting because she is not willing to be comfortable or individualistic. Today’s essay centered on the distinction between traveling and journeying.

Even the mention of the distinction sent me on a trip back in time to two very specific places. First, was my reading of Paul Bowles’ The Sheltering Sky many years ago. I went back to find the passage that came to mind in which the character drew a distinction between a tourist and a traveler:

He did not think of himself as a tourist; he was a traveler. The difference is partly one of time, he would explain. Whereas the tourist generally hurries back home at the end of a few weeks or months, the traveler, belonging no more to one place than to the next, moves slowly, over periods of years, from one part of the earth to another. . . .[A]nother important difference between tourist and traveler is that the former accepts his own civilization without question; not so the traveler, who compares it with the others, and rejects those elements he finds not to his liking.

hooks likens travel much more to Bowles’ idea of the tourist and offers journey as a word that offers truth beyond what I might find on my path. Here she is quoting James Clifford:

This sense of wordly, “mapped” movement is also why it may be worth holding on to the term “travel,” despite its connotations of middle class “literary” or recreational journeying, spatial practices long associated with male experiences and virtues. “Travel” suggests, at least, profane activity, following public routes and beaten tracks. how do different populations, classes, and genders travel? What kinds of knowledge, stories, and theories do they produce?

(I know this is heady; bear with me. I was moved be what I found today.)

The second place her words took me was back to my days teaching at Winchester High School. Every spring I took my Honors British Literature class into Boston on a field trip called “Scripting the Other.” We had been reading colonial and post-colonial literature and I wanted to find a way to make it stick. The students rotated through three or four different parts of downtown Boston—so we didn’t all clump in one place; they had simple instructions: they were to observe people and pick three they perceived as different from themselves. They had to create some sort of visual representation of each one (if the took a picture, they had to ask permission) and then write an essay for each describing the differences they perceived. The final piece was to write an essay articulating what they learned about themselves by the differences they perceived. (They did the writing when we got back to Winchester.) One of the students titled her piece “Shoe Shopping” and wrote about what it might be like to walk in someone else’s shoes. She even went back to town to check in on one of the women she met.

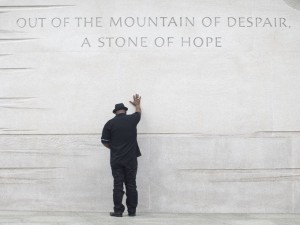

I hoped the trip would give them a sense that not everyone shared their view of the world, their advantages, or their opportunities. I also wanted them to see those differences were not necessarily deficiencies or errors; they were not things to be feared, but to be explored; they were, in hooks’ language, different journeys. She says it this way:

Theories of travel produced outside conventional borders might want the journey to become the rubric within which travel, as a starting point for discourse, is associated with different headings—rites of passage, immigration, enforced migration, relocation, enslavement, and homelessness. “Travel” is not a word that can be easily evoked to talk about the Middle Passage, the Trail of Tears, the landing of Chinese immigrants, the forced relocation of Japanese Americans, or the plight of the homeless.

Wait. I have one more stop from the past: Anne Tyler’s novel, The Accidental Tourist. It is the story of Macon Leary who wrote travel books so people could go overseas and still feel like they were at home. The point of travel was to be comfortable and safe.

The point of the journey is to see where the road takes me, to risk something to learn about where I am, to learn who is also on the journey, to remember that my perspective is not the norm or the right one. It is just one of the many stories on the trail.

My story tonight is a swirl of memory and a wish that we knew how to have conversations in this country across perceived differences that didn’t begin with labels or assumptions, but started with walking together and listening. I need to do some shoe shopping of my own.

Peace

Milton

I woke up this morning thinking about

I woke up this morning thinking about