One of the things that helped me today was a blog post by a woman named Katherine that made the rounds on a couple of Facebook feeds that I follow offering ways to respond to the mess of a world we live in these days. Here are some of the suggestions that stuck out to me.

3. Google a small-business florist near the site of any recent tragedy. Call and explain that you’d like to pay for flowers to be sent to, say, the staff of the Planned Parenthood in Colorado Springs (3480 Centennial Boulevard, Colorado Springs, CO 80907), or to Hope Church (5740 Academy Blvd N, Colorado Springs, CO 80918), where slain police officer Garrett Swasey and his family were members. When you leave a note, don’t make it about you, or your political or religious beliefs. Leave it anonymous, or simply say, “From a stranger who thought you might be sad today.”

5. There are several Dunkin’ Donuts within the general area of Sullivan House High School, the alternative school in Chicago’s South Side where Laquan MacDonald was enrolled. It’s probably a tough week for teachers and students both. Buy an e-gift card. Send the link to the faculty. Tell them a stranger bought them coffee.

6. Leave a copy of your favorite book in a public place. Trust that the right person will find it.

8. Here’s a link to Amazon, where you can buy a ten-pack of socks for $9.99. Click the link. When you are asked for your shipping address, find the address of a homeless shelter in your community. If you don’t have a homeless shelter in your community, here’s mine.

12. Go to a diner. Order a milkshake. Tip ten dollars.

13. Get a pile of index cards and a sharpie. Write down, “You are Important,” or “Breathe.” Carry them with you as you go about your day, leaving them in waiting room magazines, on car windshields, in elevators, in bathroom stalls. Keep one for yourself. We all need the reminder sometimes, too.

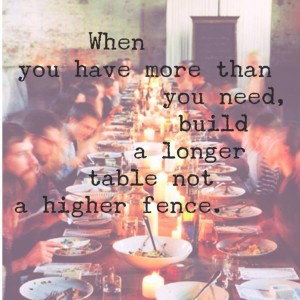

What I love about the list is how handmade it is, how incarnational. Words made flesh. Here’s what kindness and compassion and even justice look like with skin on: flowers, socks, coffee, affirmation, and extravagant tips. And it is what takes me to Bethlehem every year, and then on into the stories of how Jesus interacted with people, fleshing out love and joy and hope and compassion and forgiveness with his words and his hands. He never held a national convention, developed a global marketing strategy, lobbied for his position, or hired consultants. He thought he could change the world with a meal, a touch, and a kind word. Even when he talked about things in a more eternal sense it came down to

I was hungry and you gave me food to eat. I was thirsty and you gave me a drink. I was a stranger and you welcomed me. I was naked and you gave me clothes to wear. I was sick and you took care of me. I was in prison and you visited me. (Matt. 25:34-36, Common Bible)

Jesus noticed people others had chosen to allow to become invisible. He noticed things in people others missed. He saw beyond anger and responded to the woundedness that lay behind it. He chose belonging over blaming at every turn, and acceptance over accusation.

I know I’m not saying anything new, but then again, there’s nothing new to say, so I’m going to go back over the old, old stories and remind myself that kindness and love and forgiveness and hope are older than violence and death. I’m going back to remember the way I have felt love has been hand to hand and face to face far more than any grand gestures. I may not be able to do much for anyone in Syria or San Bernardino tonight, but I can do something for the homeless people on the New Haven Green as I walk to work from the train station, and to make sure the kindness I wish to show the world pours out first within the walls of our home and covers those closest to me. The Kindness that Became Flesh in Bethlehem calls me to do the same with every motion, every word.

My friend Bob Bennett wrote a song some time ago called “Hand of Kindness,” which you can find on this great collection, A Very Blue Rock Christmas. It feels like a good closing hymn tonight.

I have no need to be reminded of all my failures and my sins

or I can write my own indictment of who I am and who I’ve been

I know that grace by definition is something I can never earn

but for all the things that I may have missed

there’s a lesson I believe that I have learnedthere is a hand of kindness

holding me, holding me

there is a hand of kindness

holding me, holding on to meforgiveness comes in just a moment

sometimes the consequences last

and it’s hard to walk inside that mercy

when the present is so tied up to the past

and this crucible of cause and effect

I walk the wire without a net

and I wonder if I’ll ever fall too far

that day has not happened yet‘cause there’s a hand of kindness

holding me, holding me

there’s a hand of kindness

holding me, holding on to meand in the raven dark

shines a distant light

it seems to point at me

it burns away the night

familiar figure on the horizon

moving closer now I see

his heart is shining like the sun

he’s reaching out for methere is a hand of kindness

holding me, holding me

there is a hand of kindness

holding me, holding on to me

Peace,

Milton

ext of story, as stars within a beloved constellation. (198)

ext of story, as stars within a beloved constellation. (198)