I read some more of Howard Thurman’s Deep is the Hunger on the train to New York this morning, and found myself trying to imagine what he sounded like by the tone of his writing, which has a centering nature about it. I called my friend Kenny tonight, who studied with Thurman in the late seventies in San Fransisco. When I asked what his voice sounded like, Kenny said, “Deep—rich and deep;” just as I imagined. Kenny also talked about the way he told stories about things he noticed or engaged. I looked back over what I had read today and a story in the middle of one of the pieces that spoke to me. It was about waiting, which is the hardest part.

We are waiting for a storm that has been named Stella.

Thurman was talking about waiting as a synonym for patience. Here’s the story I was talking about, which has to do with a snow storm:

Several years ago, I spent three wintry days visiting Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia. A young medical student drove me in his car to keep various appointments. I was impressed with the fact that, despite the huge snow drifts, he refused to use chains. There was quite a ceremony every time he started out. First, he would let his clutch out slowly, applying the gas very gently as he chanted, “Even a little energy applied directly to an object, however large, will move it, if steadily applied and given sufficient time to work.” Not once during our experience was his car stalled in the snow. Of course, he knew how to wait. (53)

As I wait for the storm, I am waiting for the inevitable. I am waiting for something to happen to me. I have prepared as I can—bought groceries, cleared the driveway for the snow plow, brought wood into the house, charged up everything should the power go out—but waiting for a storm is mostly a passive thing. Thurman’s waiting is not the same.

Waiting was not inactivity; it was not resignation; it was a dynamic process, what Otto calls “The numinous silence of waiting.” Sometimes I think that patience is one of the great characteristics that distinguishes God from [humans]. God knows how to wait, dynamically; everybody else is in a hurry. Some things cannot be forced but they must unfold, sending their tendrils deep into the heart of life, gathering strength and power with the unfolding days. (53)

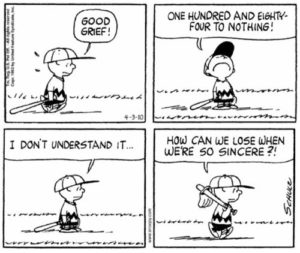

You’ve picked up, by now, that my mind works with a soundtrack. I wasn’t too far along in the quote when I heard John Mayer singing “Waiting for the World to Change.”

me and all my friends we’re all misunderstood

they say we stand for nothing and there’s no way we ever couldnow we see everything that’s going wrong with the world and those who lead it

we just feel like we don’t have the means to rise above and beat itso we keep waiting . . . waiting on the world to change

we keep on waiting . . . waiting on the world to change

From almost the first time I heard that song, I could hear that Mayer was leaning into those who had come before him. The chord progression is the same as Curtis Mayfield’s “People Get Ready.” I have no doubt that he did it on purpose. He leaned into to someone who knew more about how to change the world than he did.

But while Mayer keeps on waiting, Thurman calls us to keep on moving. He understood that his statements on patience could be interpreted to say those who are waiting for change have to just live with injustice until things turn around. So he kept writing:

There are situations that must be changed, must be blasted out, there is a place for radical surgery. Patience, in the last analysis, is only partially concerned with time, with waiting; it includes also the quality of relentlessness, ceaselessness and constancy. It is the mood of deliberate calm that is the distilled result of confidence. (54)

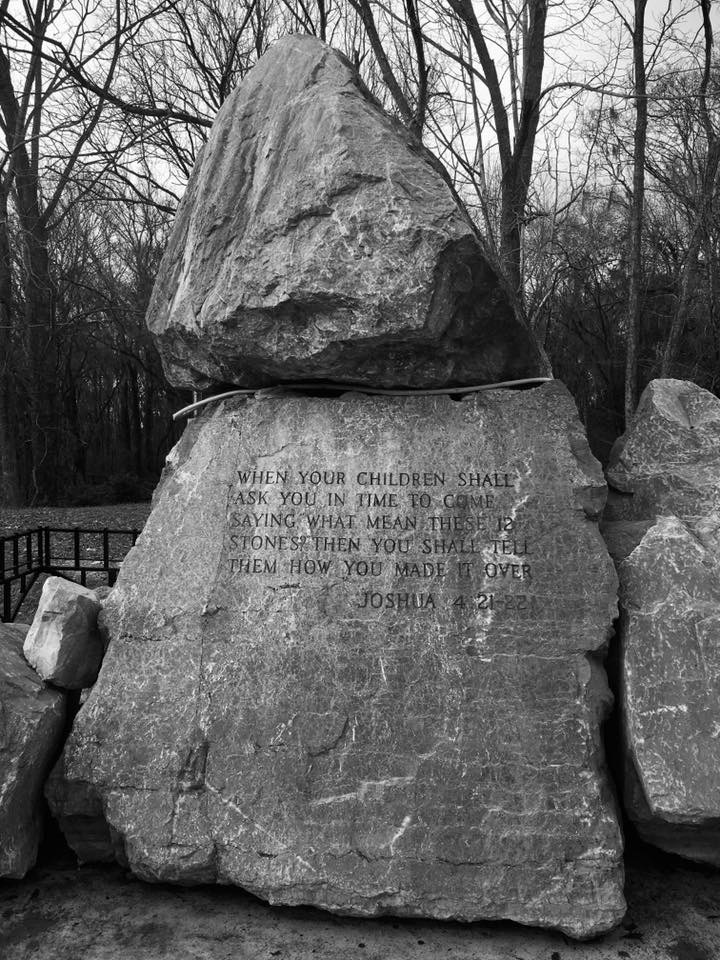

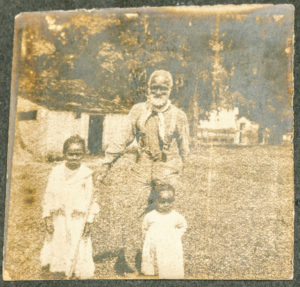

I read a story this morning in the New York Times about a group of alumni and others at Georgetown University who founded the Georgetown Memory Project. In 1838, the Jesuit university sold 272 slaves to Louisiana. The GMP site says, “University folklore says they perished without a trace, but hundreds survived the Civil War. Thousands of descendants are alive today.” They are  working now to find those descendants and find out as much as they can about the people who were sold to help the stories that have been waiting to continue. The article in the Times tells the story of Frank Campbell, one of those who was enslaved.

working now to find those descendants and find out as much as they can about the people who were sold to help the stories that have been waiting to continue. The article in the Times tells the story of Frank Campbell, one of those who was enslaved.

A little later in the morning, I received an e-mail message from Sarah, Ginger’s co-pastor, introducing us to a teacher at the high school who has been doing research on slaves in Guilford and Madison, the town just east of us. So far, they have discovered over eighty people who were enslaved here.

I am grateful for the folks at Georgetown and the teacher here in Guilford who are working to tell these stories that have been waiting to be told. I am thankful for their tenacity. Their determination. And I am reminded of how many folks in our country wait patiently—that is Thurman’s definition of patience: with relentlessness, ceaselessness, and constancy—for those of us who live by a more privileged timetable to see the injustice and to help change things. The truth is we need to be more restless, more ceaseless, more vocal (That’s not new information, that’s just me waking up.)

In another place, Thurman says, “We do not sin against humanity; we sin against persons who have names, who are actual, breathing, human beings.” (99) Like Frank Campbell. It would not be hard to name others. And they are waiting to be named.

Peace,

Milton