My head and heart are full tonight, so this post is as well.

As the news of Elizabeth Warren ending her presidential bid found me and I realized, as many did, that the election has devolved into Grumpy Old Men 3: Patriarchy and Privilege, I went back to James Cone’s The Cross and the Lynching Tree, which I finished last night.

Cone’s penultimate chapter focused on the essential place of Black women to understand the connection between the cross and the lynching tree.

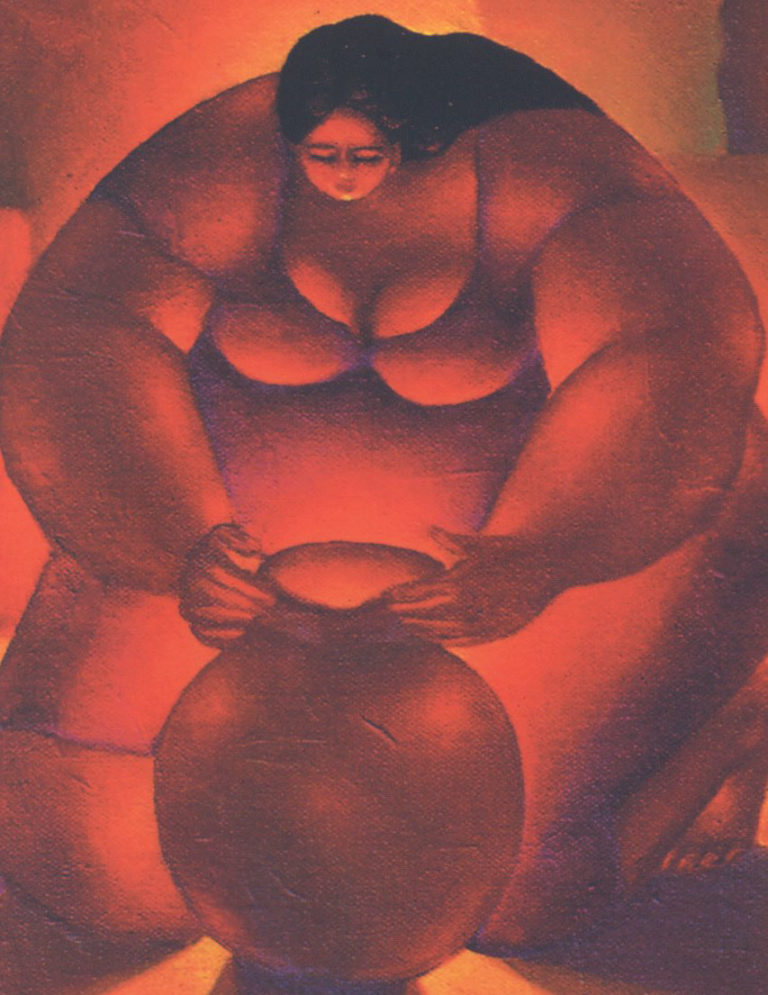

When we look at a lynched black victim transfigured as the recrucified Black Christ, we might as well be looking at “a colored woman . . . stripped naked and hung in the county courthouse yard and her body riddled with bullets and left exposed to view!” That was the point made by womanist theologian Jacquelyn Grant when she used the experience of poor black women as the lens for interpreting the meaning of Jesus Christ today. “The significance of Christ is not found in his maleness, but his humanity,” writes Grant. “This Chris, found in the experiences of black women,” “the oppressed of the oppressed,” “is a black woman.” Unfortunately, the powerful image of “Christ as a Black Woman” has been left out of our spiritual and intellectual imagination, needing further theological development.

If womanist is not a familiar term to you, here is Alice Walker’s definition:

WOMANIST

1. From womanish. (Opp. of “girlish,” i.e. frivolous, irresponsible, not serious.) A black feminist or feminist of color. From the black folk expression of mothers to female children, “you acting womanish,” i.e., like a woman. Usually referring to outrageous, audacious, courageous or willful behavior. Wanting to know more and in greater depth than is considered “good” for one. Interested in grown up doings. Acting grown up. Being grown up. Interchangeable with another black folk expression: “You trying to be grown.” Responsible. In charge. Serious.

2. Also: A woman who loves other women, sexually and/or nonsexually. Appreciates and prefers women’s culture, women’s emotional flexibility (values tears as natural counterbalance of laughter), and women’s strength. Sometimes loves individual men, sexually and/or nonsexually. Committed to survival and wholeness of entire people, male and female. Not a separatist, except periodically, for health. Traditionally a universalist, as in: “Mama, why are we brown, pink, and yellow, and our cousins are white, beige and black?” Ans. “Well, you know the colored race is just like a flower garden, with every color flower represented.” Traditionally capable, as in: “Mama, I’m walking to Canada and I’m taking you and a bunch of other slaves with me.” Reply: “It wouldn’t be the first time.”

3. Loves music. Loves dance. Loves the moon. Loves the Spirit. Loves love and food and roundness. Loves struggle. Loves the Folk. Loves herself. Regardless.

4. Womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender.

This morning I started a new book, Embracing Hopelessness by Miguel A. De La Torre. In Chapter One , De La Torre mentioned a term in Latinx theology I did not know: lo cotidiano, “the everyday along with all its particularities.”

Humans are an end, not a means. If . . . humans are the supreme subject of history, then I would argue that any construction of the God of History must orient history toward establishing justice by taking sides with the faceless under oppression–the multiple anonymous I’s of history.

I wanted to learn more, so I typed lo cotidiano theology into Google and learned about Mujerista theology and the writings of Ada Maria Isasi-Diaz, which is the Latinx sibling of Womanist theology. Isasi-Diaz said Mujeristas were those

· Who desire a society and a world where there is no oppression.

· Who struggle for a society in which differences and diversity are valued.

· Who know that our world has limits and that we have to live simply so others can simply live.

· Who understand that material richness is not a limitless right but it carries a “social mortgage” that we have to pay to the poor of the world.

· Who savor the struggle for justice, which, after all, is one of the main reasons for living.

· Who try no matter what to know, maintain, and promote our Latina culture.

· Who know that a “glorified” self-abnegation is many times the source of our oppression.

· Who know women are made in the image of God and, as such, value ourselves.

· Who know we are called to birth new women and men, a strong Latino people.

· Who recognize that we have to be source of hope and of a reconciling love.

· Who love ourselves so we can love God and our neighbor.

MUJERISTAS are those of us who struggle for justice for our mothers, grandmothers, aunts, godmothers, comadres, daughters, granddaughters, nieces, goddaughter, friends, women-partners, and for ourselves.

She wrote,

The main reasons structural changes have not come about or lasted, I wish to suggest, derives from the fact that structural change has not been seen as integrally related to lo cotidiano. To correct this, I insist, it is time we listen to Latinas and other grassroots women around the world and, drawing from their wisdom, that we conceptualize structural change in a different way than has been understood in the past. This does not mean ceasing to work on changing family structures, work- related structures, the economic structures of our societies, political structures, church structures. However, following the insights of grass-roots women, structural change must be rooted in lo cotidiano. Unless the changes we struggle to bring about impact the organization and function of lo cotidiano, structural change will not happen, and, if it happens, it will not last. We want to be clear that it is not a matter of either/or. We certainly must continue to organize, to bring about changes in the way politicians are chosen, how multinational corporations operate, how the churches control what is considered orthodox. Those changes, however cannot be conceived or brought apart from the question, ”What change will this bring to the everyday lives of poor and oppressed women?” Maybe it is time to give up grandiose plans for sweeping changes and to realize that even if those changes were accomplished they will not last unless they bring about change at the level of lo cotidiano.

Tonight, I hear Micah 6:8 in a new way:

What does the Lord require of you?

Do justice

Love kindness

Walk humbly with God

Micah is not talking in abstract terms; he’s describing how to make changes in everyday lives. Structural change must be rooted in lo cotidiano, which means my everyday life needs to be up for change as well, if I am going to help build the beloved community.

I told you my head and heart were full.

Peace,

Milton