I’m an NPR nerd.

Several years ago, when we were on a mission trip to Philadelphia, we were walking to see the Liberty Bell and passed the building that houses WHYY. “That’s where Terry Gross is,” I exclaimed. Then I laughed at myself.

Sometimes as I drive, I switch over to our local talk radio station just to see what is being said. It doesn’t take long for me to realize how accustomed I’ve become to the tone of conversation that happens on public radio because I feel accosted by the volume and venom of what I hear from the likes of Bill O’Reilly and Jay Severin who appear to relish in their rancorous rhetoric. And I’m not talking about content; I’m talking about delivery. I can’t listen for long because I’m so agitated by what I hear.

I understand the differences in opinion. I don’t understand why we have to berate and excoriate one another.

When I punched in on Saturday, the talk was about Al Gore’s winning of the Nobel Peace Prize. I managed to hang in for most of my ride to work because I was intrigued by the reticence to give any credence at all to the reality of global climate change, or (perhaps, better put) to make climate change a partisan issue. I know there are more ways to look at the causes and consequences of our presence on the planet that what can be seen in An Inconvenient Truth and that a fair amount of what passes for “the environmental movement” is fleeting fashion. I am not a global warming fundamentalist and I take our human impact on the planet too seriously to leave it to the posturing of our politicians and actors. So enough about them. I’ll talk for me.

I wrote a few weeks back about my discomfort with the old gospel hymn that begins,

this world is not my home

I’m just a-passing through

my treasure’s all laid up

somewhere beyond the blue.

The song comes to mind again this morning because I think it voices an error in Christian theology that has left us behind the curve on environmental issues (understanding of course, that the response of Christians is not monolithic). Much of evangelical Christianity, which is where I grew up, has seen the need to care for our planet as superfluous at best. What I remember being taught, basically, was the point of our being here is to get everyone to heaven and our stay here is temporary anyway. Going green doesn’t rank high on that list of priorities. Though we talk more about the environment in the liberal branch of Christianity where I have found a home, we hop too easily onto the cultural bandwagon, picking up the slogans but not necessarily being any more substantive in our stance. On both ends of the continuum, we seem to see the issue as political and/or social before we think of it as spiritual. And we preach at each other much more than we converse.

Here’s my attempt to do the latter on this Blog Action Day.

“God claims Earth and everything in it, God claims World and all who live on it,” proclaimed the Psalmist (24:1, The Message), pulling together our care for the planet with our concern for one another, and calling us to a more thoughtful, intentional, nuanced, and incarnational theology that perhaps most of us want to engage. If that verse is true, then life has no discards; every action matters. I have to consider, as I stand in the supermarket, that the bananas from Costa Rica that cost me 69 cents a pound do not reflect the real cost of the fruit. Seriously. I can’t fly to Costa Rica for 69 cents a pound. Am I to believe that the people who picked them were paid a living wage and the owners of the farm are making the best environmental decisions for that kind of money? I might do well to consider another source of potassium for my diet.

Yikes. I’m dangerously close to preaching and not talking.

One of the best sermons I ever heard on the parable of the Good Samaritan was called “Christ in the Ditch.” (If I could only remember who preached it.) The point was the Christ-figure in the story was not the Samaritan, but the wounded one left for dead by the side of the road. Our call is to allow the Jesus in us to respond to the Jesus in those who have been discarded and beaten up by the world around them. We incarnate God’s love best when we see Jesus in the ditch. If God is in the downtrodden, then we might pull the psalm and the parable together to say God is in the dirt as well. What we do to the planet, we do to God. Like the old song says:

When through the woods, and forest glades I wander,

And hear the birds sing sweetly in the trees.

When I look down, from lofty mountain grandeur

And see the brook, and feel the gentle breeze.

Then sings my soul, my Savior God, to thee,

How great thou art, how great thou art.

Then sings my soul, my Savior God, to thee,

How great thou art, how great thou art.

Why I carry my recycling bin to the curb every Tuesday morning makes about as much sense as why I get up and go to church on Sunday morning or why we put our twenty-five bucks in the pot at Kiva.org so one woman in Mexico could try a make a living selling tacos. It doesn’t make sense, but it makes faith. We were breathed into existence by a God who relishes in what one life can do. The universe our God created is layer upon layer of infinite and infinitesimal activity, the minute and the magnificent both packed full of significance. Rather than oscillate between the arrogance of thinking we can do whatever we want without consequence to creation and the cynicism that says nothing we do matters anyway, let us choose the narrow path of intentionality and hope, believing that every step chosen well leads us closer to being the creation God imagined in the beginning.

Peace,

Milton

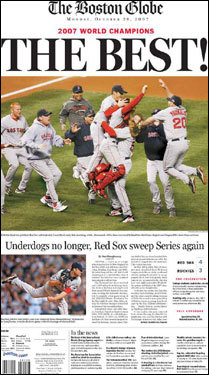

Some time this summer, as it became apparent that the Red Sox had an amazing team, I said to Ginger, “Wouldn’t it be great if the Sox won the World Series as we were leaving New England.” Last night, as you may have heard, they obliged. For the second time in four years, our boys are the champions.

Some time this summer, as it became apparent that the Red Sox had an amazing team, I said to Ginger, “Wouldn’t it be great if the Sox won the World Series as we were leaving New England.” Last night, as you may have heard, they obliged. For the second time in four years, our boys are the champions.