It would be interesting to trace the transformation in American society that broke the link between popular religion and high intellectual achievement, between religious enthusiasm and generous and transformative change. In my experience, many of the schools in the old abolitionist archipelago are entirely forgetful of their history, or are embarrassed by the little they know about it, in most cases because they are very progressive and enlightened and therefore do not wish to trace their paternity to a clutch of fiery preachers, and in some cases because they are piously conservative and do not enjoy association with a clutch of New England radicals.

Marilynne Robinson, “A Great Amnesia” in Harpers Magazine, May 2008

Good and bad, I define these terms

Quite clear, no doubt, somehow.

Ah, but I was so much older then,

I’m younger than that now.

Bob Dylan, “My Back Pages”

I do wonder how you went from ministry at Pecan Grove, Texas to the UCC church and working as a chef, but maybe that is a long story?

It would be fascinating if you are ever in the mood to tell it.

Brenda, in an email to me

I’ve been turning Brenda’s request over in my mind for several days. I wish I knew a way to tell a short version, or to tell one in which I didn’t feel like I was leaving out major chunks, or running the risk of being misunderstood. That said, the practice of trying to tell the story has been an important one for me, so it feels worth sharing.

One more thing: this version is more of an emotional landscape than a chronology or even autobiography. I tried to find the line that runs from the God I first knew as a little boy to the God I trust now.

_________________________________________

I don’t remember a time in my life when I didn’t know that God loved me. I was born into a strong Southern Baptist family where my parents sang hymns to me to put me to sleep (many of which I still know). When I was five years old, I gave my heart to Jesus. I wasn’t converted. I’m not sure I became a Christian in any understandable sense. I didn’t turn from a life of sin and sex and drugs. I did what a five year old would do: I gave my heart away. Then I told my three-year-old brother he was going straight to hell if he didn’t give his heart to Jesus. Ah – memories.

As much as I knew God loved me, I’m also pressed to remember a time when I didn’t feel like that love (or anyone else’s) had to be earned, or I had to prove myself worthy of receiving it. As far back as I can remember being loved, I can also remember not feeling like I was enough, in most any sense of that word. I worked hard to be good, to be best, to be at the top of the heap. It wasn’t a competitive thing for me, primarily; I just wanted to prove myself. I was a fairly compliant teenager. I didn’t get into a lot of trouble because I was mostly worried about disappointing my father, the preacher. It was many years before I realized I had had a hard time figuring out where God stopped and Dad started. The good side is that dynamic kept me out of a good bit of trouble. The downside is I defined myself by who I thought people around me wanted to be. I took my cues from them.

I went to Baylor University primarily because that was where all of my family had gone. I didn’t even apply to another school. I “surrendered for ministry” (an interesting Baptist phrase) primarily because that was the family business. I started pastoring (at Pecan Grove) at the end of my junior year because a family friend who had pastored there called and said he thought it would be a good match. I graduated from college and moved up I-35 to Southwestern Seminary because that’s where everyone else was going. Again, I never thought to look anywhere else.

All of them were good experiences. (OK – the group of us who hung together at Southwestern to survive were worth remembering; I have done my best to never step on that campus again.) I pastored that little church for four years. I loved my time at Baylor, even though I feel far from the person who walked that campus. Even as I was doing all the right things, my inner contradictions were breaking the surface. At the end of my first semester of seminary, and after Alabama had drubbed Baylor in the Cotton Bowl, I stood on a table in George’s, a legendary bar in Waco, after way too many beers and sang, “Jesus Wants Me for a Sunbeam.” Most of the crowd knew the words and sang along. I didn’t know what to do with feeling somehow at home in that bar, even as I felt at home at church.

I don’t want to over-romanticize the moment. I was dead drunk and making a fool of myself. My internal conflict lasted long after the hangover was gone, however. To speak in the terms of the emotional landscape I mentioned at the first, the way my heart has housed my insecurities has always pulled my gaze to the margins. I’ve never felt as though I had a guaranteed place in the in-crowd, so I’m drawn to the others who stand outside the circle, for whatever reason.

The fundamentalist overthrow of the Southern Baptist Convention began while I was in seminary. The fight was then, and continued to be, much more about politics and power than it ever was about theology. The push to get everyone in lockstep let me know I was quickly becoming a Baptist at the margins of the denomination.

After seminary, I moved east from Fort Worth to Dallas, at the suggestion of one of my professors, and completed eight units of CPE (Clinical Pastoral Education), which was sort of like emotional surgery without anesthetic. The premise of the program is you learn who you are by examining what you say and do – scary stuff for a guy like me who didn’t know how to integrate the various faces I presented to the world around me. Needless to say, I found my way to therapy. From there, I found my way into youth ministry, in large part because I had been doing youth retreats and people told me I was good at it.

I was the Minister to Youth/University at University Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas for six years. I was good at it. I loved working with junior high and high school kids – their lives were at the margins. My memories of high school were mostly of wishing I could have been anyone else but me. I knew their pain, I took them seriously, and I loved them. It was good combination. As the eighties drew to a close, the denomination I knew was falling a part. The hardliners were vicious and tenacious and those who saw themselves as moderates had been caught by surprise and were left to define themselves by who they weren’t rather than who they wanted to be. (I understood the dynamic quite well.) It all served to make me mad.

One of my former professors told me he thought I should start working on a PhD in New Testament at Baylor, so I did. I drove from Fort Worth on my day off and took two seminars that fall. In January I met Ginger and, for the first time in my life, felt unconditionally loved. By the end of the spring semester, I decided I wanted to be in love with her more than I wanted a doctorate, so I withdrew from the program. We married in April, 1990. Though I was happy in my work, we were both feeling more and more alienated from Baptist life. We needed to be in a more open place. A perfect storm of a new pastor at UBC who wanted to see me leave, a realization on my part that I was going to explode in anger if I didn’t get out of Texas, and a chance to go to Boston to try and start a church led us to move to Charlestown in August of that year.

For four years we worked to start a church in our neighborhood. We both had to get other jobs because of the way the whole enterprise was funded. Ginger managed a group home for troubled adolescents and I got a job substitute teaching. The church didn’t take. We realized we weren’t evangelists. Ginger moved to a job as the youth minister at First Congregational Church, Winchester. She went on to transfer her ordination to the UCC (boy, is that the short version!) and we found a home at the church there. I was raised – well, I think — in faith by a very conservative denomination and found a home in the most liberal mainline Christian denomination – “the last house on the left,” as they say. And I am at home here.

I went back to school and got my teaching certification and my masters in English because a position opened. Once again, I loved being with the kids. Ten years of bureaucracy and the coming of standardized test took their toll. I also struggled with grading. I hated it. For me, good teaching meant inviting the students into an honest relationship of trust and sharing. I wanted them to feel safe enough to risk and grow. Then came the end of the semester and I betrayed the whole enterprise by saying, “Your life is a C.” At least that’s how it felt to me, the one who felt as though he wasn’t that good at making the grade.

When we moved from Winchester to Marshfield, I stepped out of the classroom and fell off into the bottomless darkness of depression. Looking back, I can see where it also showed up along the way, but for about eighteen months all I could do was get out of bed, walk the beach, and try to write poetry. Early in May eight years ago, Ginger said, “I know this has been hard, but you have to make some money.” I spent the next week driving all around the South Shore trying to figure out what I wanted to do. For the first time, I was looking for a job based on what I wanted to do, not because someone told me I was good at it.

I came home with two jobs. The first was a part-time gig at the South Shore Music Circus, a summer open-air music venue. I went in to see about a stage crew job and got hired as security, thanks to my size and my shaved head. The other was a cooking job. I knew the kitchen was a depression free zone for me, so I thought that might work professionally. I talked my way into a job at a small place that was just opening. By the time the restaurant did open, I had to take time off for a church mission trip. I got back to find the chef and the owner had gotten into a big fight the night before and she had fired him. I was the only one in the kitchen who spoke fluent English, so she put me in charge. Joao and Carlos, the two very capable Brazilian cooks taught me how to do my job. The restaurant didn’t last but six months, but I’ve been cooking ever since.

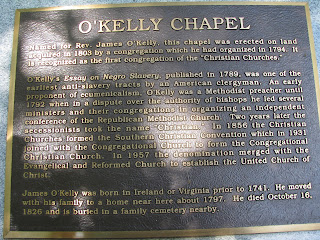

When we moved to Durham, I moved as a chef. Fifty-one years on, I’m doing what I most want to do: cook and write. I’m a member of a church of ”extravagant welcome,” which comes through in what we say each week: whoever you are and wherever you are on life’s journey, you’re welcome here. I have dear friends who have stayed in Baptist life. I couldn’t do it. My anger would have gotten the best of me. I don’t do well when people are drawing lines to decide who is in or out, who is acceptable or not. (I make that statement to say more about me than them.) I’m a part of a people who ordained a black man to pastor an all white congregation before the Civil War, who ordained women sixty years before they could vote, and who ordained the first openly gay man as pastor in the seventies. I belong to a church that looks to see who is standing at the margins and brings them in. I belong here.

I’m almost halfway to fifty-two and I still can’t remember not knowing that God loves me – that hasn’t changed. What has changed is I’m better at trusting that God loves me because I’m breathing, because I’m here and created in God’s image. That’s enough.

Peace,

Milton