As someone who lives with hearing loss, depression, and two titanium knee joints, I found preaching on Paul’s metaphor of the Body of Christ (I Corinthians 12:12-31) to be multi-layered. Seeing ourselves as a body—a connected organism of relationships—is more than imagining some sort of cosmic game of Operation.

Here is where the metaphor took me.

________________________________

It was a brilliant idea in the beginning. Paul found a small group of Christians who had ended up in Corinth for one reason or another, so he started a house church where they began worshipping together. They took Jesus’ call to share their faith seriously and began to invite others. As word got out, some folks came on their own and found their place in the fledgling congregation.

But a new city meant a new way of being. The churches that had started in Jerusalem and Palestine had been mostly monocultural. The Corinthian church took on the personality of its host city: diverse, questioning, even a little wild in places. Based on Paul’s words, we know rich people, poor people, free people and enslaved folks, and a variety of ethnicities were trying to figure out how to live together.

It was a brilliant idea, but it started coming apart at the seams once Paul left town. He was the one committed to the idea and maybe he thought he had the “buy in,” as we like to say sometimes, but his dream wasn’t as easily transferrable as he thought. Because he couldn’t get back to them in person, he wrote letters—probably more than the two we have—to give advice, to offer correction, to underline his affection for them, and to try and give them new ways to imagine what it meant to be church, which meant giving them new vocabulary.

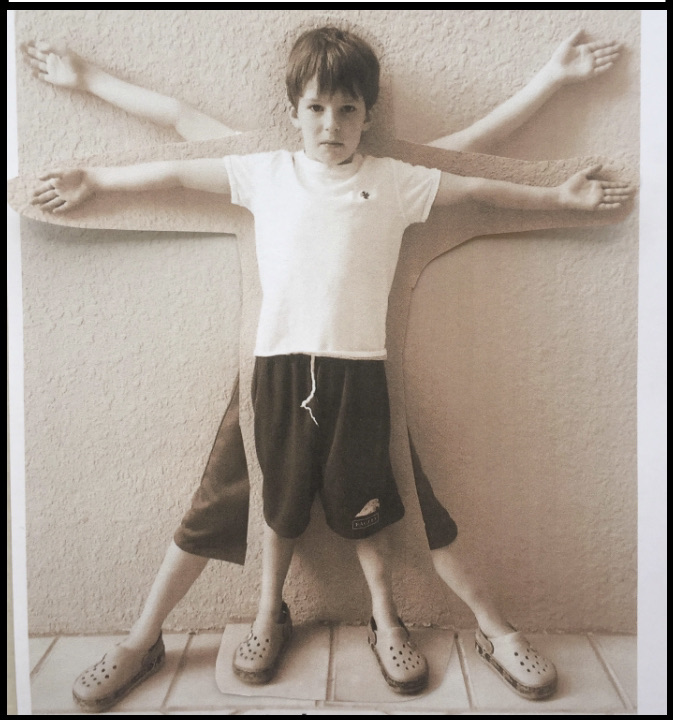

One of those new images is at the heart of our passage this morning: the metaphor of the church the Body of Christ. Paul was trying to offer a metaphor that would help them move toward unity and greater acceptance of one another, so he called them the Body of Christ and then laid out what it means to be a body: looking at the different parts, learning to work together, needing each other to be healthy and whole.

I learned from the writer John Berger that in Greek the word metaphor shares a root with the word for porter, as in the porter on a train who helps you and your bags get from place to place, which is another of saying a good metaphor takes us on a journey of understanding. It’s an invitation to use our imagination.

A good metaphor is a wonderful thing because when we find new words with which to define ourselves or approach a problem, we create possibilities. But a metaphor can grow stale if we forget to keep telling the stories behind it, or we decide we know all the angles. And we have to remember that any metaphor has its limitations.

The best example I can think of is using Father as a name for God. Any name for God is a metaphor—a way of describing God that helps us catch a glimpse of one we cannot completely comprehend. If father is the only metaphor—or even the primary metaphor—we use for God, then those who have problematic relationships with their fathers really struggle to find God in that metaphor. And offering a bigger picture of God requires more imagination than just adding Mother to the list. God is more than a heavenly parent. God transcends gender. Even in scripture, God is a rock, a river, and a lion. The more metaphors we employ, the more our faith can grow.

We often talk about church as a family, or a community of faith—like we are our own little village. Paul says we are a body, and not just any body: we are the Body of Christ. Since Jesus no longer walks the earth as the Incarnation of God’s Love, we are the ones who incarnate the love of God in the world. And the metaphor is singular. We are not the bodies of Christ; together we make one body, just as all the various elements of our human bodies all work together. It is the image at heart of our UCC motto: that they all may be one.

I don’t know how people were in Paul’s day, but in our time, I think the body is a complicated metaphor because, as both individuals and as a society, we have complicated relationships with our bodies. We are bombarded with images of what we should look like, and we are offered any number of ways to alter our bodies to try and make them look like those ideals. Many of us struggle with not weighing what we wish we could, or not being able to do things we want to do or dealing with some sort of condition or disability that makes life more difficult. As one who has profound hearing loss, what it means to be an ear, for example, is a multi-layered metaphor.

On the other hand, perhaps it is precisely because none of our bodies work perfectly that we can understand Paul’s idea. He’s talking about what it takes for a body to be healthy. He was addressing a congregation that was, as we said, fairly fractured. Those in places of privilege made a point of distancing themselves from those who were not. People were quick to make sure their rights and their needs were taken care of before they thought about anyone else. The church was a body at war with itself and Paul was trying to move them beyond their self-absorption to some sense of solidarity. He hoped the metaphor of the Body of Christ would help them see how desperately they needed each other and how desperately God needed them to need each other; he wanted them to grasp what real love looked like.

Because Paul talked about the roles people played in the church in Corinth and the different gifts people had to offer, it is easy for us to think that we are valuable to God because of what we can do. That’s particularly true as Americans reading these verses because we are so immersed in a cultural work ethic that thinks the only ones who matter are those who produce. We look at bees and ants as metaphors for good workers, but we aren’t bees or ants. As Katherine May says in her book Wintering,

Usefulness, in itself, is a useless concept when it comes to humans. I don’t think we were ever meant to think about others in terms of their use to us. . . . We flourish on caring, on doling out love. The most helpless members of our families and communities are what stick us together.

We can feel God in the beauty of the sunrise, or the magic of waking up to new-fallen snow. We can catch a glimpse of the extravagance of God’s creativity we when look at the mountains, or stare out over the ocean, or play with a puppy, but we learn what love is from one another. Love is incarnated: it comes in the flesh. It has hands and feet and eyes and ears, and it shows up with soup when we are sick, and it listens when we are struggling, and it admonishes when we screw up, and it forgives.

Most of that will show up in next week’s sermon, which is on 1 Corinthians 13—the chapter after the one we read this morning that most people know as the Love Chapter—but for now let me give you a simple illustration of what love looks like.

One of the things I have learned about my hearing as I have dealt with its diminishment is–well, several things. One is that we don’t hear with our ears; we hear with our brains. If I want to hear better, I have to concentrate. One of the incarnations of love that Ginger, my wife, offers me is room to focus and find my way when I get lost in the noise of life. Often, when we are in a restaurant (remember eating in restaurants?) she will hear a song she likes and ask, “Can you hear the song?” When I say no, she will tell me what it is and then I can usually hear it. I get to be a part of her joy in that moment.

It’s a small thing, but that is what love looks like.

Much is written these days about a growing understanding of the integral connection between our bodies, our minds, and our spirits. None of it is new knowledge, mind you. Ancient cultures knew these things, but, particularly as our technology advanced, we compartmentalized them, so we are having to relearn is that everything is connected and interdependent. Whatever physical issue I have has mental and spiritual implications; what I read and think about plays out in my body. In the same way, the metaphor of the Body of Christ calls us to relearn that to see everyone as a part of the body means to pay attention to one another, not just to make room, or to make accommodation, but to offer invitations to connectedness. To incarnate love.

Earlier in the sermon, I said that when Paul called the church the Body of Christ, he saw it as the continuation of the incarnation: those who follow Jesus are God’s human expression of love.

I love that idea, but I want to add a qualifier: those who follow Jesus are one of God’s human expressions of love. Christians don’t have a corner on the love of God. In fact, we would do well to ask ourselves how expansively we are willing to hear the metaphor. Just how far a journey will we take? How big a body are we talking about? Who is a part of the body? Is it just this congregation? Is it the Southern New England Conference of the UCC? Is it all Christians? Is it everyone in the world? The rhetorical answer to all those questions is yes, but what is our honest answer? Just how far will our attention and intention reach? Are we willing to accommodate the visitor who sits in our regular pew, for instance?

In some ways, that last question is overwhelming because none of us can meet all the needs we are aware of, much less all the needs in the world. I don’t have the capacity to fully take on world hunger and human trafficking and dismantling racism and climate change. Neither do you. But as a body—a bundle of relationships working together—we can do it. When something pulls at your heart, speak up. When someone else speaks up, listen. And then work together. We all have something to offer each other, and we all have things we need from one another. But even as I say that I want to say, again, that reason we are a part of the body is not because we are useful. We are a part of the body of Christ because every last one of us is a person wonderfully created in the image of God who is worthy to be loved just because we are breathing.

Paul was right: church was a brilliant idea in the beginning. I think it still is, even as much as the Body of Christ has been through over two millennia that has left it kind of beaten up and limping along. But we said at the start that this is a complicated metaphor. A body does not have to be perfect to be alive and functioning. As the people of God, we are the human face—and hands and feet and voice and heart—of God in the world.

Let us love one another. Amen.

Peace,

Milton

So good! So so good! Thank you!

an Idea turned brilliant!

Let us strive to live this message, Thank you, Milton!