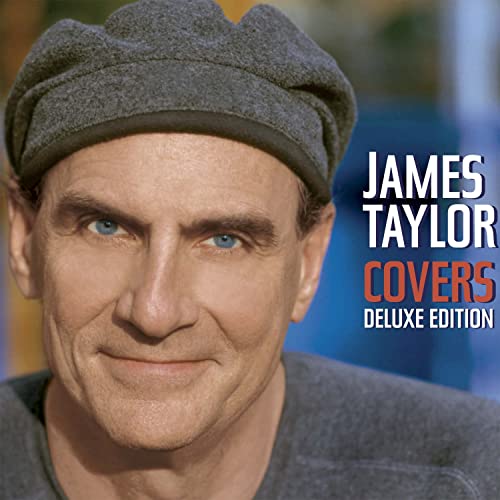

On our trip to Texas, we stopped for coffee somewhere south of Waco and, along with our beverages, we picked up James Taylor’s new CD, Covers, to give us a break from the radio. As I said earlier this week, my life is a movie in search of a soundtrack. A couple of cuts in, I could feel something change inside me as he began to sing, “I am a lineman for the county.” I have loved “Wichita Lineman” since I first heard Glen Campbell sing it on a record my parents had, to when I learned Jimmy Webb wrote it, to when I heard Jimmy Webb sing it, and on down until JT’s soft, well-weathered voice carried the words and music as we drove up that Texas highway last week.

On our trip to Texas, we stopped for coffee somewhere south of Waco and, along with our beverages, we picked up James Taylor’s new CD, Covers, to give us a break from the radio. As I said earlier this week, my life is a movie in search of a soundtrack. A couple of cuts in, I could feel something change inside me as he began to sing, “I am a lineman for the county.” I have loved “Wichita Lineman” since I first heard Glen Campbell sing it on a record my parents had, to when I learned Jimmy Webb wrote it, to when I heard Jimmy Webb sing it, and on down until JT’s soft, well-weathered voice carried the words and music as we drove up that Texas highway last week.

The BBC said it was No. 87 of the Top 100 Songs and Rolling Stone put it at No. 187 of it’s Top 500 Songs of All Time, right after “Free Bird,” which makes for an interesting juxtaposition. Here are the lyrics:

I am a lineman for the county.

and I drive the main road

searching in the sun for another overloadI hear you singing in the wire

I can hear you thru the whine

and the Wichita lineman is still on the lineI know I need a small vacation

but it don’t look like rain

and if it snows that stretch down south

won’t ever stand the strainand I need you more than want you

and I want you for all time

and the Wichita lineman is still on the line

From my earliest memories, the song is tied to “Gentle on my Mind,” which was on the same record. Both of them are unusual love songs, I suppose, and I sang along heartily even though I had no idea what he was singing about, other than I liked the word pictures of

moving down the back roads by the rivers of my memory

and for hours your just gentle on my mind

As I have heard “Wichita Lineman” over the years, I’ve come to see it as a tenacious love song. Here’s a guy who is dutifully doing what he thinks needs to be done and, even in the midst of his hard work, love comes singing to find him. The lines that kill me are

and I need you more than want you

and I want you for all time

and the Wichita Lineman is still on the line

Ginger and I talked again today about how our work schedules – OK, mostly mine, since I work five nights a week, and this week, six – keep us from eating dinner together or being able to get out and do much. Maybe the song hits because I feel like the Bull City Line Cook who is still on a line of his own. Most any afternoon, one of us calls the other and says something like, “I just missed you and wanted to say, ‘Hi’.” Even though the phones have nothing to do with lines anymore, I can still hear her heart sing. However the equation of need and want plays out, what I understand almost twenty years on is the tenacity of love is not about hanging on, or hanging in there, but about diligently boring into one another’s beings and determinedly tightening the bonds between us, regardless of schedules and duties and whatever else life may hold. Whether all has been said and done, or there is still much to do and say, we are together.

And we have music to play as we go.

Peace,

Milton