I found it a wonderful example of spiritual synchronicity to discover that the Gospel reading for World Communion Sunday was the story of Jesus’ encounter with the one we call “the rich young ruler.” For those who don’t know the story, a wealthy young man comes to Jesus and asks what he must do to have eternal life. Jesus says, “You know the commandments,” and then proceeds to rattle off a few of the Thou Shalt Nots, which the young man quickly claims to have kept since he was a child. Jesus cuts to the chase: “Go sell everything you have and give it to the poor—that will do it.” The Gospel account says the man went away sad. He just couldn’t do it.

Jesus doesn’t call out to him or go after him. He turns to his disciples—whom, Mark says, were shocked—and tells them it was easier for a camel to get through one of the narrow gates in the city called the Needle’s Eye than it was for a rich person to walk away from his or her privilege. When they wondered out loud who could be saved if the rich and privileged could not, Jesus added, “With God, all things are possible.”

Say it with me: with God, all things are possible.

In a world that has more displaced people than at any time in our history, that knows more about war than anything else, and in a country addicted to violence and self-absorbed protectionism, the recklessly hopeful celebration of World Communion Sunday matters deeply. I look forward to this first Sunday in October when we are intentional about noticing the tether of grace that binds us together across boundaries and biases, theologies and denominations, personalities and politics. (And yes, I understand, as my wonderful Episcopalian editor once told me, for those who observe the Eucharist every week, every Sunday is World Communion Sunday.) Together at the Table we affirm that grace matters most, which is most difficult for those of us who are people of privilege—and that’s pretty much everyone who stumbles across this post.

As Ginger unpacked the passage in her sermon, she reminded us we were not free to regard the young man as someone unlike ourselves. “Everyone in this room would have somewhere to go if we lost everything; we could find a couch to sleep on for the night.” In my notes, I jotted down, “Grace is for rich people, too.” It’s not that our compassion is invalid. The problem lies in that when we see the homeless person on the corner, or the masses of refugees fleeing conflicts in their countries, or people in our own land being harassed, arrested, and even killed because of their skin color, ethnicity, or religion, we do not see ourselves. We don’t think they are one of us. We don’t understand how our sense of privilege separates us. As Jason Isbell sings:

you should know compared

to people on a global scale

our kind has had it relatively easy

When Jesus began the Beatitudes with, “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven,” I think he meant those who are hopeless, or downtrodden, or marginalized, or desperate have a better grasp of grace than those of us who, as Ann Richards once said of George W. Bush, were born on third base and think we hit a triple. The reason, for example, that the killings on our country are not going to stop is because the discussion begins with our rights to own guns rather than our calling to protect one another. Jesus’ call to the young man was to see himself as part of humanity rather than seeing everyone else as the cast in a movie about him.

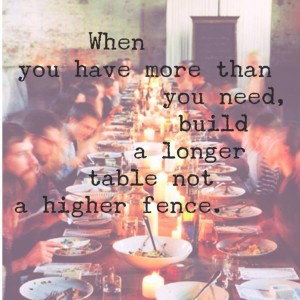

Over the past few weeks, a couple of friends have posted a picture on my Facebook page of a long  table full of people that looks a bit like our dinners on the porch the last few weeks with the caption, “When you have more than you need, you build a longer table not a higher fence.”

table full of people that looks a bit like our dinners on the porch the last few weeks with the caption, “When you have more than you need, you build a longer table not a higher fence.”

Yes. Yes. Yes.

The reality of my life is I have more than I need—even in the months when we have not been sure how all the bills would be paid. Beyond the economics, I am a straight white male. I am a person of profound privilege. For me to understand what it means to be hopeless and desperate—to be poor in spirit—means I must do way more listening and learning than preaching or pontificating. It means when I do speak, I need to speak up for someone other than myself. I need to give up being right, or in charge, or in control. I need to let go of assuming life will always allow me to be comfortable. I need to let go of what I have and trust that God’s grace covers me as well; I need to come to the Table to be fed, to feel connected, and to be reminded that grief, grace, and gratitude are inextricably bound to one another.

With God, all things are possible.

Peace,

Milton

With a friend last week I was wondering why it is so DIFFICULT to understand that we ARE the lowliest peoples we encounter? If you are in distress, then I am in distress. Why is that so hard?

I am just catching up on reading. Which means I’m reading this after attending my college homecoming – a time where it’s so easy to fall into moments when you are tempted to compare what you have to what others now have. I wrestle with other’s looking at my life and responding, “You have been through so much” or some similar sentiment. It’s jarring and immediately puts me on the offense. I think, “But I’ve had a good life. Don’t think less of me.” I don’t have integrated thoughts on that yet – merely an awareness that I don’t take time as much as I should to contemplate how I measure the abundance of life. But somehow, it begins with my understanding that I am not better than or less than. That we are all the same. We all have more than we need. We all have the ability to share. We are one.