My sermon on Jesus’ parable of the pharisee and the tax collector hinges on a re-translation by Amy-Jill Levine that opened up the story for me.

__________________________

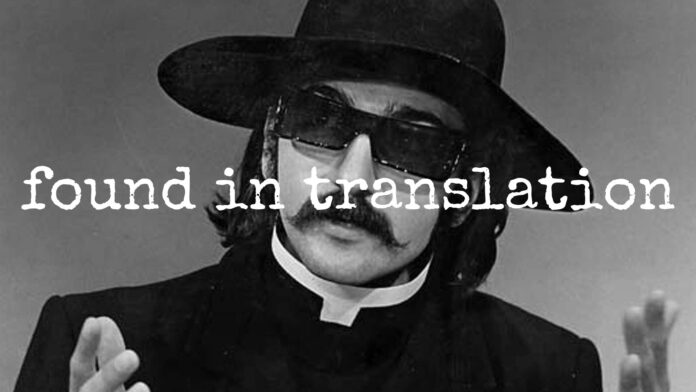

In the early days of Saturday Night Live, one of the repeating characters was a priest named Father Guido Sarducci. He was not a priest of course, but he played one on TV. One of his ideas was what he called The Five Minute University. He said people spend a lot of money on college and then forget most of what they learned, so he could save anyone a lot of time and money by enrolling in his university that lasted only five minutes, graduation included.

The idea was that in five minutes you would learn what the average college graduate remembers five years after they get out of school. For Spanish, you would learn to say, “¿Como está usted?” which means, “How are you?”, and also the response, “Muy bien,” which means, “Very well.” Economics class boiled down to supply and demand: you buy something and then you sell it for more than you paid for it. Theology was simply, “God is everywhere because God likes you.”

I was actually in college the first time I heard Guido do his routine and, I have to say, it sounded pretty tempting. Sometimes it feels like it would be nice if more things could be distilled into sentences that were easy summaries that we didn’t have to think about again.

But that’s just not the way life goes.

Jesus’ approach to teaching was quite different that Father Sarducci because he didn’t offer a whole lot of easy summaries or catch phrases. Sometimes he listed things, like the Sermon on the Mount, or he said what he meant in a sentence or two, but there was always more for his followers to learn. Jesus taught in layers that require of us to keep digging, to keep looking, as our Congregational forbearers said, for more light to break forth.

To keep growing, we have to keep learning. Part of that, particularly when we come to scripture and theology, is to read and listen in a way that we can be caught by surprise, rather than living with expected summaries as though it were a course in the Five Minute University.

With that in mind, the sermon is going to feel a bit more like a Bible Study because we need to dig in a bit.

Last week, as we talked about the widow and the judge, we saw the way Jesus took characters that could be stereotyped and broke those images wide open so we could see something else. The same is true in today’s parable.

Once again, the story is brief. Two men came into the Temple to pray. One was a Pharisee. I want to stop there for a moment and ask what image comes to mind when you hear the word Pharisee. My guess is it is not very positive. Across Christian history, we have often painted them as arrogant and even dishonest. We even added the word to our language to mean someone who is self-righteous and hypocritical.

Theologian Amy-Jill Levine, who is a Jewish New Testament scholar, reminds us that to most of Jesus’ audience, the Pharisees were respected teachers “who walked the walk and talked the talk.” The apostle Paul was a Pharisee and saw it as a mark of distinction. They were not priests, so the man in our parable was not on his home turf in the Temple. He, like the tax collector, had come to pray as part of his faith commitment.

The tax collector was a Jewish man who worked for the Roman government, which meant he was not necessarily the most popular man in town. People often thought of tax collectors as dishonest, and he might have been, but this man was in the Temple praying for forgiveness. The conventional reading of this parable would have us hear it much like the painting on the front of our order of service, where the Pharisee appears rich and well-dressed and the tax collector looks poor, worn, and left out. Amy-Jill Levine says that’s not the case. He lived in the center of society and probably did pretty well for himself.

This is not a story of a rich person and a poor person.

Instead of comparing and contrasting the men to get meaning from the parable, Levine invites us to read the prayers of the two men at face value: the Pharisee is offering a prayer of gratitude, and the tax collector is offering a prayer of repentance. She says people in Jesus’ day would have had a hard time thinking that the tax collector’s prayer would have been answered, that he would have been justified. They would have expected it, as far as the parable goes, but they would not have liked it.

Then she went on to say that part of the problem we have with the parable, as modern readers, is that our translations play to the stereotypes that have been handed down. For her, it all swings on one key preposition in the sentence in today’s passage, “I tell you, this person went home justified alongside of the Pharisee.”

If you were to open our pew Bible and turn to Luke 18, the sentence would read, “I tell you, this person went home justified rather than the Pharisee,” as if Jesus were making a point about the religious teacher.

Here’s the thing: Both translations are accurate because the Greek word—para—can mean both things. It comes into English in words like parallel, paradox, parable, even Paraclete, which is one of the names for the Holy Spirit. We are used to it meaning alongside, or with. To understand why most Christian translators have chosen words that separate the two men would mean talking about church history for longer than you would want to stay this morning. For now, let’s stay with the text.

Last week, I said that in the parable of the widow and the judge Jesus was asking us to pray for justice, which meant looking at whoever we see and not seeing adversaries or enemies; but seeing people who hurt like we do; about listening to the voices God puts in our ears and answering them in love.

In this companion story, then, wouldn’t it make sense that Jesus was making connections rather than comparisons as a reminder that God’s love can heal all kinds of brokenness when we come willing to be healed. Whatever issues we might have with the Pharisee or the tax collector, God listened to both of them. As I have said before, faith and life are team sports.

Immediately following this parable, Luke says people were bringing their babies to Jesus to have them blessed and the disciples scolded the parents, telling them Jesus had more important people to see. Jesus intervened to welcome the little ones and say they were the ones who really understood how God was at work in the world. That is followed by a visit from a rich young man who what it took to find peace with God, but prefaces his question about what he had to do to be right with God by saying he kept all the rules, much like the Pharisee in our parable. Jesus told him to give away all of his wealth to those in need—to see himself as alongside of everyone.

The young man couldn’t do it. Can we?

Life is hard and stressful and sad, which makes it tempting to reduce those with whom we struggle to convenient labels, to decide we know who they are and what they think, and then write them off, making our Five Minute University Theology class sound like, “Jesus loves you but I’m his favorite.”

Life is also beautiful and surprising and complicated, which means we are called to drop the labels and look at the people, to tell stories rather than sling slogans, to do the wonderful and messy work of living alongside of each other so that everyone gets to know what love feels like.

May we have the courage to find translations the create greater room for God’s love to envelop us all. Amen.

Peace,

Milton