Though I preached this sermon only a couple of days ago, the events of the week have continued to unfold. Rather than try to update it, I will let it stand as its own little time capsule, even as I continue to figure out how to respond to what is happening around us.

“Two Questions”

1 Kings 19:9-18; Matthew 14:22-33

A Sermon for First Church of Christ, Congregational, East Haddam, Connecticut

August 13, 2017

Perhaps it will come as no surprise that I spent a good bit of time last night rewriting my sermon after the events in Charlottesville, Virginia over the last few days. Off and on yesterday, I read news reports online and followed the Facebook feeds of friends who were in Charlottesville to stand against the terrorism, violence, and hatred being inflicted on that community. They sang, “This Little Light of Mine” and they stood in silent solidarity. They did not respond to the violence with violence. Choosing to strike back is not a solution that offers hope. I prayed a lot, sent notes of encouragement, and wondered how to make a meaningful response from what feels like so far away. Then I went back to the two stories we read this morning.

Both Elijah and Peter were working out what it meant to be a person of God in difficult times.

Elijah had the title: he was a prophet with a capital P, which sounds important. Yet, when we join him, he is holed up in a cave by himself hiding. God finds him with a question: why are you here?

The self-pitying prophet answers with a woe-is-me tale: “I’ve been zealous and doing my job, but no one is listening but me, no one is keeping the covenant but me; they’ve chased the other prophets off, and I’m hiding here because I’m afraid for my life.”

God was having none of it. “Go outside and wait for me.” Elijah didn’t move, but God still put on quite a fireworks show: a gale strong enough to break rocks in two, an earthquake, and a fire—but God inhabited none of them. Then came what the King James Version calls “a still, small voice,” the translation we read this morning calls “the sound of sheer silence.” There was no voice—only a deep, compelling, gigantic silence.

I read that verse, and all I could think was

hello darkness, my old friend

I’ve come to talk with you again . . .

In the presence of the silence, Elijah couldn’t sit still. It was the presence of God—the being, not the action—that moved him from his hiding place to the mouth of the cave; God met him once more with the same question: Elijah, why are you here?

Hang on to that question and let’s switch stories.

Though our gospel reading started at Matthew 14:22, it is part of a larger story that begins in verse one when Jesus gets word that John the Baptist had been executed by Herod. Jesus was deeply saddened and wanted to get away to have time to grieve. He and his disciples headed out into the desert. The crowds wouldn’t stop following. They ended up in a remote spot with thousands of people and no food. They found a sack lunch of five loaves and two fishes that Jesus turned into a giant picnic. Once everyone was fed, they tried to get away once again. This time, Jesus took down to the water and all but threw them in a boat and went off by himself to find some solitude.

Some time in the night, a storm came up. Since many of the disciples fished for a living, a storm on the sea of Galilee, which is about as predictable as stand-still traffic on I-95, would not have been an overly frightening thing. They knew how to survive a storm. What they didn’t know was what was going to happen to the rest of their lives. John had been murdered. The political situation, if you will, was changing around them. The crowds were getting bigger and harder to control and understand. Jesus kept trying to get off by himself. They could feel things were changing, that they wouldn’t stay the same forever, or even for very long. The storm was just happened to provide a working metaphor for it all.

In the middle of the night and the storm, Jesus came walking across the lake. Silently. They thought he was a ghost, at first; then they realized it was Jesus, and he said, “Take heart. It’s me.”

The translation is worth noticing again. Some translate Jesus’ words as, “Don’t be afraid,” but it is more than comfort. Take courage. Take heart. It was a call to fortitude, to faith—a gut check.

In the second phrase, Jesus was doing more than identifying himself. He was proclaiming his presence: “Take heart. I am,” reminiscent of the way God answered Moses when he asked whom he should say sent him to Pharaoh—God said, “Tell them I AM sent you.”

Just as Elijah had moved to the mouth of the cave when he heard the silence, Peter moved to the edge of the boat and said, “Command me to come to you”—call me to do what you are doing. Jesus simply answered, “Come.”

Peter was out of the boat before Jesus put the period on his short sentence, and he was walking on the water. All of a sudden he noticed the wind the same way Wylie Coyote noticed he had followed the Road Runner off of the cliff in the old cartoon, and he started to sink. He cried out for help and Jesus caught him. As he helped him into the boat, Jesus asked Peter a question: What made you lose your nerve?

For most of the week, the sermon I was going to preach was about the importance of living our lives with a sense of appropriate insignificance. What I mean is, yes, we are wonderfully and uniquely created in the image of God and worthy to be loved, and so is everyone ever created. It matters that we are here for our days on the planet and when we die, life will go on without us, thank you. It was a good sermon, yet, in the wake of Charlottesville, the two questions carried a deeper sense of urgency: Why are you here? What made you lose your nerve?

Jesus reinforced words from his Hebrew upbringing when he said, basically, that the answer to why we are here is to love God with all of our beings and love our neighbors as ourselves. That word neighbor might as well read “everybody you can.” Love those who live in fear when they see mobs of white terrorists carrying torches, and love the terrorists.

The prophet Micah said what God requires of us is to do justice, love kindness, and walk humbly with God. Cornell West said, “Never forget that justice is what love looks like in public.” Justice is not about payback or revenge. It is also not silent. Though we may have had a lot of silence in both of our stories this morning, but now is not the time for us to be.

Then we answer the first question—that we are here to love God and to love one another—calls us to face the second question as American followers of Jesus: what made us lose our nerve?

I am not saying Charlottesville happened specifically because we failed to do something. I am saying the racist attitudes that manifested themselves as the organized chaos of terrorism in Virginia are alive and well in our northern neighborhoods, in conversations we hear in our coffee shops, in the way our cities and towns remained divided by race and economics.

Most of the white men who marched yesterday were millennials, which means they were born after the Civil Rights Movement, after Martin Luther King’s words became a part of our cultural vernacular. They are not “them”—they are us. We have to find the nerve to tell the story differently. My wife Ginger is a part of a group in Guilford who have been researching the eighty enslaved people who lived in our little town. One of them was owned by a pastor at the Congregational Church. Slavery stopped in the north, in large part, because it was not economically viable. Our geographic location does not mean we automatically get to claim the high road. And many of our denominational forebears had the nerve to follow the convictions of their hearts and fight for abolition because of their faith in Christ.

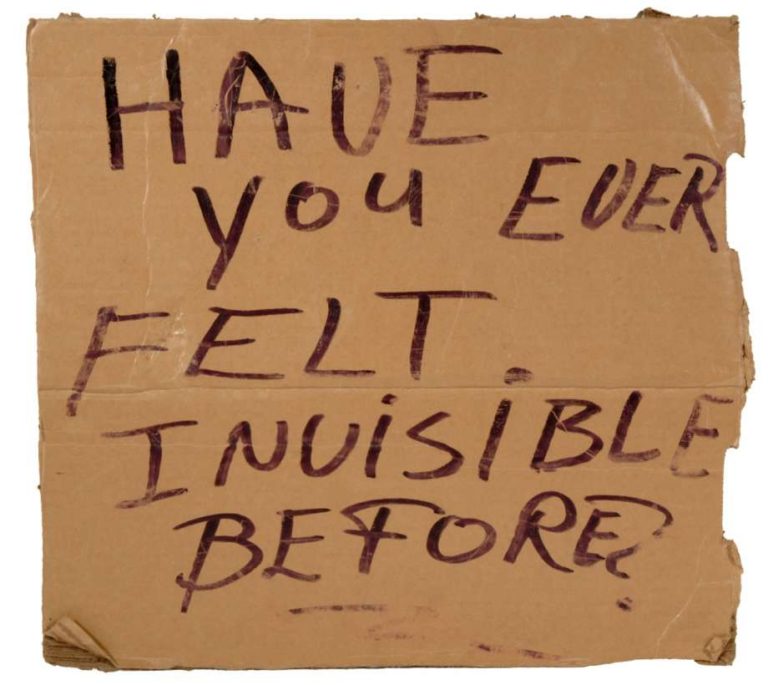

How do we find the nerve to speak up in Jesus’ name? How do we find the nerve to live with disquieting compassion? To let our little lights shine? How do we find the nerve to look within ourselves and within our community and ask what we need to do to change? How do we work for that change and not just talk about it?

In a few moments, we will share Communion together. We often present the Eucharist as a comfort food: Christ gives us life in the bread and the cup, in his body and blood. I want to invite us to be discomforted by the meal this morning.

On the night Jesus was betrayed—and he could already feel it coming—he took the bread and he broke it and he had the nerve to say, “This is my body broken for you; this is my blood poured out for you. As often as you share this meal—maybe any meal—remember I had the nerve to love you.”

Maybe I am preaching the sermon I first thought of. Our days are numbered. It matters that we are in this place for these days. We will not be here forever and we are here now. The reason we are here is we are called to love the world. May we find the nerve to do so. Amen.

Peace,

Milton