This morning I started a new book, or I should say restarted; it is another that has laid fallow for some time. The book is After the Locusts: Letters from a Landscape of Faith by Denise M. Ackermann, a South African feminist liberation theologian. The book was a gift from my friend Kenny.

In the introduction, Ackermann says, “After the Locusts is about my efforts to discover what is worth living for in troubled times.” She wrote the book in 2003. Each chapter is a letter to someone in her life. The letter I read this morning was to her granddaughters. Early in the chapter she says,

To help me find my way through many questions, doubts, and discoveries, I want to imagine that I am sketching a landscape. Unlike professional cartographers I do not want to be tied down to the certainty that, provided the measurements are right, this sketch will be a reliable guide in all circumstances. This is not an accurate map. It is really like a giant picture with different landscapes and figures, swarms of locusts and fields of flowers, different colors and symbols; it requires imagination, even guesswork, and it is always provisional.

I got as new car about a year ago and, for the first time, I have a screen in the dashboard that lets my plug in my phone and use the map feature. All I need is the address for my destination. Not only will it provide directions, but it will even reroute the trip when it gets word of an accident or road construction. Much in the same way that I no longer know anyone’s phone number by heart, I don’t know directions to many places either. Getting lost is becoming less and less of a possibility–or at least that’s the illusion created by my device. The other casualty is that I am no longer required to remember how to get somewhere–unless I make a point of remembering.

As Ackermann writes about how she wants her granddaughters to know what matters most to her, she also talks about remembering.

Guided by a memory that often fails me, I want to mark our different histories and identities and what the mean for me as your grandmother. Memory is not fiction, yet once I begin to recall emotions, events, and places, I wonder–is that true? How much of memory is invented or rearranged? Did that happen or am I remembering being told it did? Fragments, tainted memories, stories retold too often are all I can offer.

I read her words after I returned from an early-morning pre-op appointment with my orthopedic surgeon. (I have a left knee replacement on September 29.) We talked through things I needed to do between now and then, what to expect at the hospital, and then what to expect afterwards. He is the surgeon who replaced my right knee two and half years ago. I said something about feeling easier because I knew what to expect and he said, “Yes, and I find that most of my patients say they had a harder time with the second one. I don’t know if that is true, or if they just can’t remember how much the first one hurt or how hard the recovery is from this surgery.”

I remember it hurt and that rehab was hard, but my strongest memories are walking around the town green and Ray from the hardware store coming to cheer me on. I remember the first time they got me up to walk after my surgery that I was aware the it hurt to walk but it was not the same pain that made me have to use a cane.

As I journaled this morning, I came to the realization that this onset of depression is more severe than what I thought at first. I have a better understanding of what it does to me and I feel like I have worked hard on developing better tools to deal with it, and this time it is taking me out. When I finished writing, I went to tell Ginger about my insight. She started nodding before I had finished talking and said, “This is worse that it was twenty years ago.”

The sense of feeling like I am walking around in a concrete suit or treading molasses in an endless lake that is deeper than I am tall is not new, yet the strongest memories of twenty years ago are walking with Ginger and feeling held by her tenacious love for me, even in the middle of the mess.

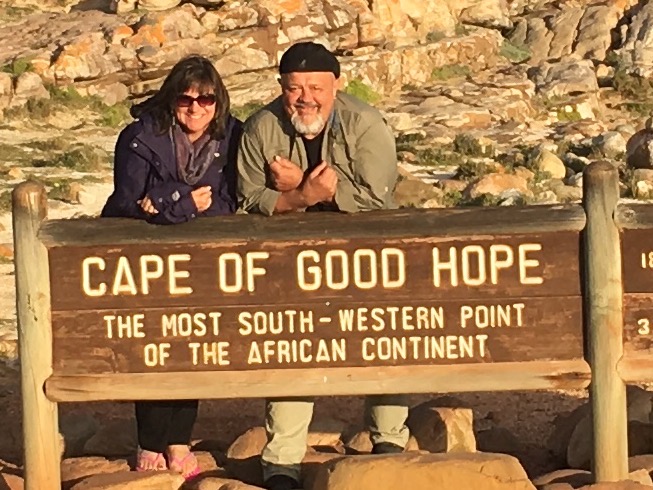

My father’s birthday was September 13. He would have been ninety three. There are about fifteen years of our lives together that were difficult for us both. We didn’t know how to talk to each other and when we did we mostly did damage. We both learned how to offer more grace than judgment to one another over time, and I am grateful we had time to figure that out. These days, the memories that rise to the surface are ones that connect me to him. I have caught myself over the past couple of months starting any number of sentences with, “My Dad used to tell a story about . . .”–so much so that Ginger commented, “You’re missing him, aren’t you?”

How much of a memory is invented or rearranged?

To re-member is to put the memory back together again, and I think that happens much like the sketching she described and less like the precision of the professional cartographers. Her comparison makes me think of James Cowan’s novel A Mapmaker’s Dream, a story about a fifteenth-century monk who decides to draw the definitive map of the world without leaving his cell. News of his projects attracts travelers from all over the world who want to tell their stories, which requires of him to come to terms with a world he cannot quantify.

Six centuries later, Denise Ackermann says of her sketch, her map of memory and meaning, “It requires imagination, even guesswork, and it is always provisional.”

Yes. Yes, it does. Thank God.

Peace,

Milton