As I begin another year of writing each day during Advent, beginning with the sermon I preached this morning seems right. It is where the season is starting for me: in the shared space of life in my congregation. I am not following the lectionary this week and took Isaiah 35:1-10 as the jumping off spot for my words, looking at the way stories get lived and retold as we seek to continue to learn from them. Happy Advent.

_______________________________

When I say the word prophet, what images come to mind?

The word itself comes from roots that mean “before-teller,” “harbinger,” or “proclaimer,” all of them carrying the idea of one who speaks for God. Down the years, the word has also come to carry the idea of one who predicts what’s going to happen in the future, but that misses the mark because, though they are talking about what might happen, or maybe even what will happen, most of what prophets say carries a note warning or perhaps admonition, to call people to action.

As one of my seminary professors said, the biblical prophets were “forth-tellers” not “foretellers.” They weren’t reading crystal balls; they were interpreting the consequences of the present. Sometimes they offered words of correction, or even judgment. At other times, as in our reading today, they offered words of hope and encouragement.

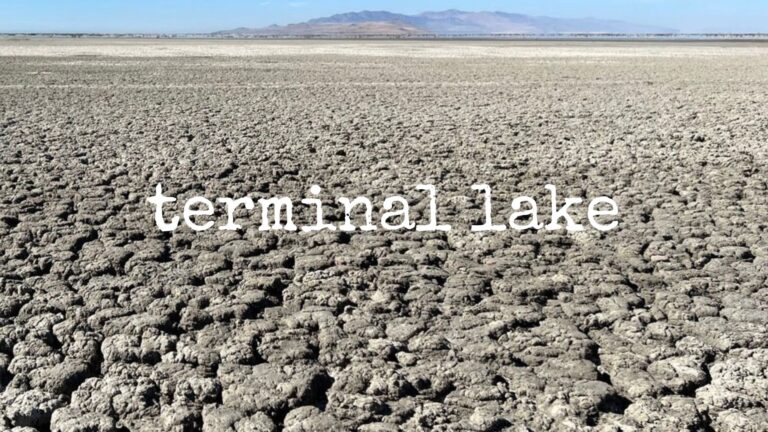

Isaiah was a forth-teller who spoke to the Judean people during a time of exile when they were far away from their homeland and had been for many years. When he spoke about the dry lands being joyful and the wilderness blooming, he was doing more than giving them an image-filled pep talk. He was not an optimist telling the people the sun will come out tomorrow. He knew change wasn’t going to come quick, necessarily, and he wanted the people to remember—to trust—that God had not abandoned them; and then to live like God had not abandoned them, to be open to the future and the possibility that God could bring about significant change in and through them.

“Through them” is key to the whole idea because the way God brings about change is with and through people who trust that it is possible. Judea would bloom again when people went back to the burned out and abandoned land and recultivated it, when they got out and dug in the dirt and planted things. The love of God requires human incarnation in order to change the world.

Perhaps that is why those who followed Jesus leaned back into Isaiah and some of the other prophets as they began to collect and tell the stories that became the foundation of our faith, re-membering Isaiah’s words in a new way that saw Jesus’ birth as validation of the truths the prophet had spoken. Isaiah didn’t know about Jesus, but when Jesus’ followers remembered what the prophet had said, they made new connections to their own lives of faith in Christ.

Let me tell you a story to explain what I mean by that kind of re-membering.

When my father pastored in Houston, one of the children’s Sunday School teachers told him what had happened that day. She taught a class of four- or five-year-olds, and she was describing what Jesus was like—he was kind, he was friendly, he listened to people. After almost every characteristic she named, one of the little boys would raise his hand and blurt out, “I know him. He lives on my street.”

She tried to explain that Jesus lived long ago, but the little boy was unflappable: “I know him. He lives on my street.” They got through the lesson and when the little boy’s mother came to get him, the teacher told her what had happened. The mother smiled and said, “There’s an old man who lives on our street who is the kindest, gentlest, and most loving person we have ever met. Many of our neighbors have said he is more like Jesus than anyone we have ever met. So, yes, he does live on our street.”

The followers of Jesus read Isaiah and, like the little boy, said, “I know him. He lived on our streets.” They re-membered Isaiah through the lens of their present tense, of their moment of struggle and oppression and difficulty, much as we do when we come, once again, to Advent and to remember the story in our time. Our sense of exile, our feelings of despair, our grief, even our hope, are not tied to the same circumstances as the Judeans of Isaiah’s time or those of Jesus’ followers, and yet the promise that God has not deserted us still matters, and so we read ourselves into the old stories, even as we remind ourselves that there is a difference between living a story and remembering or retelling it.

One of the prophetic words I come back to most every Advent—words I quote to you every year—comes from twelfth century mystic Meister Eckhart, who said, “What good is it to us that Mary gave birth to the son of God two thousand years ago, and we do not also give birth to the Son of God in our time and in our culture? We are all meant to be mothers of God. God is always needing to be born.”

To walk through these days of Advent is about more than going through the ritual that has been handed down or lighting the candles and singing the songs because it is tradition. Most of our ways of remembering—the things we say and sing and repeat—were not a part of the actual birth of Jesus. They are memories and rituals handed down to help us re-member the story in our time.

Though we mostly talk about it as a season of waiting and anticipation, the word advent means “arrival” or “approach.” It carries its own momentum: something—someone—is coming.

These Advent Sundays as we will observe them lead us to several arrivals: next week, John the Baptist, then Mary, then Jesus, each of them calling us to ponder how we will live out our response to their arrivals, how we will incarnate the love of God in a new way in our time and in our culture, which is another way of saying how we will live out our trust that God is capable of making streams in the desert and giving sight to those who cannot see.

But how do we look at our world and honestly trust that kind of change is truly possible? Perhaps the better question is how can we afford not to trust it?

How will the world change at all if we are not willing to trust God enough to dig riverbeds and do what we can to help those around us see that they are wonderfully and uniquely created in the image of God and worthy to be loved?

We retell these stories to remind ourselves that in order of Christ to be born anew in us means we must open our hearts with expectancy for the almost unimaginable good that the love of God can accomplish in and through us in even the most unexpected places, as well as in the most common places in our lives, we must choose to let the story be re-membered in what we say and do, such that when our neighbors hear our story they, too, will say, “I know Jesus. They live on my street.” Amen.

Peace,

Milton