Our first full day in Istanbul has come to a close.

Our first full day in Istanbul has come to a close.

We arrived yesterday evening, landing on the eastern edge of Europe to be met by Onal, our host from Kirkit Travel, with whom we have only communicated by email to this point. It was nice to know that someone who knew our name really was there to pick us up from the airport. We we teaken to the Tashkonak Hotel, which is within walking distance of the Blue Mosque, as well as in singing distance of it and several others; even in a short time, we have become accustomed to hearing the Muslim calls to prayer beaming out from the minarets five times a day. Since Istanbul has 3,200 mosques (and the population is 94% Muslim), the wonderfully melodic calls stack on top of each other in serendipitous harmony as their different songs and styles float across the city.

I’m getting ahead of myself.

Istanbul is city of 14 million people. As I said, 94% of them are Muslim. Three and a half percent are Christians (157 churches) and one half of a percent of the population is Jewish (with twenty-two synagogue s). Can you tell I paid attention on the tour? Our tour guide, Alsi, took us to the Blue Mosque, the Hippodrome, the Aya Sophia, lunch along the water, the Sulemanni Mosque, and the Topkapi Palace, all the while filling our heads with facts and stories, which run deep in this place.

s). Can you tell I paid attention on the tour? Our tour guide, Alsi, took us to the Blue Mosque, the Hippodrome, the Aya Sophia, lunch along the water, the Sulemanni Mosque, and the Topkapi Palace, all the while filling our heads with facts and stories, which run deep in this place.

For her, history began with the founding of Constantinople in the late fourth century. Constantine built a city and named it after himself. She told it as though nothing significant had happened here before that. Yet, the Greeks had had a city here – Byzantium – centuries before Christ; the Romans had been here, too. But Turkish history seems to work hard to leave the Greeks out of as much as they can; the Greeks are happy to return the favor, still refusing to call Constantinople by the Turkish name it has had for almost a century: Istanbul.

No matter who we are, when it comes to history we tell the story the way we need to hear it – or perhaps the way we wish it had been – which then allows us to see the present the way we want it to be as well.

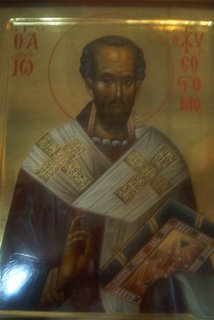

The two mosques were beautiful and quite active with both tourists and worshippers. We all had to take off our shoes, but those of us who came to look were limited in the part s of building where we could go. At Suleman’s Mosque, we saw where the men wash themselves before they pray to purify their hearts in prayer so both bocy and soul be clean. Aya Sophia began as an Orthodox church, was converted to a Catholic church after the Crusaders sacked Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade (they were supposed to go to Egypt but didn’t get that far, so they wasted this city instead), remaining so for about fifty years until becoming Orthodox again, only to becoming a mosque when the Muslims conquered the city. One of the rulers who followed made it into a museum, so it is the one building we saw where both Christian and Islamic symbols of worship exist side by side, though no official worship takes place in the building. I found a sort of strange comfort and hope in seeing the images side by side.

s of building where we could go. At Suleman’s Mosque, we saw where the men wash themselves before they pray to purify their hearts in prayer so both bocy and soul be clean. Aya Sophia began as an Orthodox church, was converted to a Catholic church after the Crusaders sacked Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade (they were supposed to go to Egypt but didn’t get that far, so they wasted this city instead), remaining so for about fifty years until becoming Orthodox again, only to becoming a mosque when the Muslims conquered the city. One of the rulers who followed made it into a museum, so it is the one building we saw where both Christian and Islamic symbols of worship exist side by side, though no official worship takes place in the building. I found a sort of strange comfort and hope in seeing the images side by side.

At one point along the way, our group got to go around the circle and tell where we were from. It was then I realized that this is the first time I have been in a tourist city where the majority of the tourists are not American. We had twenty five people on our bus with people from Croatia, Serbia, Iran, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine, Mexico, Germany, Romania, Portugal, and Pakistan. Ginger and I were the only Americans. I’ve never thought about where Croatians and Serbs go on vacation before.

We ate lunch with Sohail, a Pakistani banker, who was a very pleasant and gentle man. He lived in the US for ten years and went to the University of Chicago. His wife, I found out, grew up in Lusaka, Zambia and went to the same school I had attended when I lived there (though several years after me) . He had a deep love for his country and couldn’t say enough about how much we would enjoy it if we were to go there. He and his wife had been in the restaurant at the top of the World Trade Center just weeks before September 11, 2001; he spoke with fondness about their time there and with sadness about the attacks.

We talked about the differences in how governments act and how the people they supposedly represent actually feel. None of us felt particularly well represented by our leaders. They are retelling history, or at least repackaging it, to fit where they need it to fit so they can convince us what they say is the way things really are, the primary message being, “Be afraid; be very afraid.”

Why do we settle for that?

When we came out of the Sulemanni Mosque, I asked the guy from Iran how the mosques we had seen compared to the ones in his country. He told me very energetically how much larger and more beautiful the mosques were in Iran, going into significant detail. Then he said, “I am not Muslim; I’m Christian. But the mosques are beautiful.”

Iran is 97% Muslim and I got to talk to an Irani Christian who was in Istanbul on vacation. Even as our governments sling ultimatums, we were walking the cobblestones streets trying to understand each other.

I know the diplomatic problems of the world won’t be solved by a day long tour on a bus. I know fuzzy little anecdotes about multicultural munch outs are not necessarily substantive. I know there’s a lot of crap going on out there that makes it easy to choose to be frightened. I also know I don’t want fear to get the last word.

When we left the palace, the bus turned down a narrow little street to begin dropping us off at our hotels. From the first narrow street, he turned down a smaller one, cutting the corner closely. When the left rear tires cut across the curb and manhole cover, the pavement gave way and the back wheels dropped into the hole. We were stuck. We all got off the bus so another one could take us to our various lodgings. Ginger and I were close enough to the Tashkonak to walk, which also afforded us the chance to find the restaurant where we wanted to eat dinner. One of the tour company folks gave us directions back to our hotel which took us down some small and very quiet streets. For five minutes or so, we were pretty lost; then we found a street we knew and, soon after, the hotel. It was a little unnerving, but mostly because the city is new to us; we were not threatened by anyone.

When we left the palace, the bus turned down a narrow little street to begin dropping us off at our hotels. From the first narrow street, he turned down a smaller one, cutting the corner closely. When the left rear tires cut across the curb and manhole cover, the pavement gave way and the back wheels dropped into the hole. We were stuck. We all got off the bus so another one could take us to our various lodgings. Ginger and I were close enough to the Tashkonak to walk, which also afforded us the chance to find the restaurant where we wanted to eat dinner. One of the tour company folks gave us directions back to our hotel which took us down some small and very quiet streets. For five minutes or so, we were pretty lost; then we found a street we knew and, soon after, the hotel. It was a little unnerving, but mostly because the city is new to us; we were not threatened by anyone.

The last paragraph is not intended to be either allegorical or parabolic. Take it at face value: here in a country that borders those whom CNN and Fox tell me are all throwing fits and chanting, “Death to America,” I spent a fascinating day getting to know people who are as unsure of what my government is trying to do as I am of theirs. As the calls to prayer wafted through the night air like an exotic aroma, I found comfort and was moved to pray as much with them as for them.

Peace,

Milton