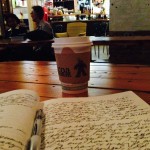

Over the past several weeks, I have been working towards another book. What that means for me is a string of almost daily photos from Cocoa Cinnamon, our neighborhood coffee shop, of my coffee, pen, and notebook because I find it best to write in longhand in the early stages. I like thinking through the pen rather than the keyboard, and my journals don’t have internet access. I still don’t know exactly what kind of shape the book is going to take, but I do know it’s about home.

Home.

For someone who has spent most of his life moving around, it’s an elusive target. I have a growing collection of songs and poems, of quotes and quips, each one offering its take on what home is. It is safe to say you will hear more about both the ideas and whatever they become in the days and weeks ahead, but tonight, as I was sitting here in my favorite coffee shop thinking about Advent, a new thought crossed my mind as I imagined Mary and Joseph packing up to go from Nazareth to Bethlehem.

In those days a decree went out from Emperor Augustus that all the world should be registered. This was the first registration and was taken while Quirinius was governor of Syria. All went to their own towns to be registered. Joseph also went from the town of Nazareth in Galilee to Judea, to the city of David called Bethlehem, because he was descended from the house and family of David. He went to be registered with Mary, to whom he was engaged and who was expecting a child. (Luke 2:1-5)

Joseph and Mary were the first ones who had to go “home” for Christmas.

Though they lived in Nazareth, the census required them to register in Joseph’s hometown, so they hit the road, third trimester and all, so they could be counted in the place that mattered. Though Joseph’s family heritage was there, they had no relatives to count on for lodging and support. Still, they went as they were told and it came to pass that Jesus was born in Bethlehem. Even today, the birth city gets much more attention than the place where Jesus grew up. No one goes to Nazareth on Christmas Eve. And I wonder if they ever took Jesus back and said, “Well, son, there’s the barn where you were born.”

Home.

When I was in sixth grade we lived in Fort Worth, Texas. I had not been in America since my kindergarten year. I walked home from my first day at Hubbard Heights Elementary School and said, “Mom, I met the weirdest kid today. He’s lived in the same house his whole life.” (By that time in my life, I had lived in four cities, three countries, and gone to four schools. I, like Jesus, had moved quickly after I was born.)

My brother said, “There were three or four kids like that in my class.”

And my mother said, “I hate to tell you boys, they aren’t the weird ones. Lots of people live that way.”

I was in the country of my birth, but I wasn’t at home. When I went back to Africa, I wasn’t sure how to feel at home there either. As I sit here in the coffee shop, I feel at home and yet also know that my roots run about as deep as the potted plant on our porch that looks settled there as well. One good pull and that all changes.

Jesus spent a couple of years in Egypt running from Herod before he finally got back to Nazareth. I can picture Mary and Joseph sighing with relief, “Home!” and Jesus wondering what all the fuss was about. To him, it was just another new town, except this time with a few more relatives.

Home.

Yesterday in church, I accompanied my friend Jennifer as she sang,

I am a poor wayfaring stranger

a-traveling through this world of woe

but there’s no sickness toil or danger

in that bright land to which I go . . .

She sang after our time of prayer requests, when we had voiced our joys and concerns, our grief and pain. The song carries an odd comfort for me because I have sung it for so many years and it also calls me to claim I want to be more than a passing stranger in these days I am on the planet. Today I spent part of my afternoon walking with my friend Tim as we both are working for there to be less of us on the planet; before I walked with him, I spent some time reading from a book of Wendell Berry essays he loaned to me called What Are People For? In one of the essays is about Huckleberry Finn, Berry defines what it means to be a part of a beloved community, which could be a name for home, and he says it is where we go to hurt together. Hurting in isolation leaves us strangers; sharing our grief, our tragedy in community creates the room for redemption and forgiveness.

Home.

My morning started here at Cocoa Cinnamon. I met an artist here named Jim. He is a metal sculptor, among other things. We were meeting to talk about spiritual direction and how I might study with him to help me figure some things out. Tonight as I came in, I saw Leon, the owner with his wife Areli of this wonderful place, and we talked about when we might share a meal together. In between I walked with Tim and with Ginger, which we have done together in several places, and ate dinner with Melinda who traveled from Birmingham to surprise my mother-in-law, Rachel. Though I am traveling through this world of woe, I am not a stranger.

When the alarm goes off at 6:30 in the morning, it will be almost exactly four months to the minute that the phone rang in August to tell me that Dad had died. My traveling through this day will remind me I do not bear my grief alone. I am surrounded by many hearts and hands willing to share the load, even as I do what I can to help carry theirs as well. Roots or not, they treat me like I’m home.

Peace,

Milton