Because I went to the gym this morning, I saw the message on my dashboard that my car was due for servicing and I remembered to make an appointment when I got home. The Honda dealership had an opening this afternoon, as did I, so I told them I would be there around 2 o’clock. When I told Ginger my plan for the day, she said, “Eli’s is across the street. I’ll go with you and we can have lunch.”

And so we did.

Eli’s on the Hill is one of six restaurants with the same name dotted across southeastern Connecticut. It’s good food in a comfortable atmosphere. The bar at the restaurant in Branford is large and U-shaped. It was not crowded when we got there, so we sat at one bend in the U and ate and talked until the car was ready. The scene, for us, was familiar. We spend a lot of time eating and talking together, in a variety of settings.

At one point, Ginger asked, “What are your favorite things to do with me?”

I thought for a moment, and I answered something I don’t remember now because it wasn’t the best answer. Then I said, “This. Sitting and talking with you when we hadn’t planned for it.”

She agreed it’s one of our best things.

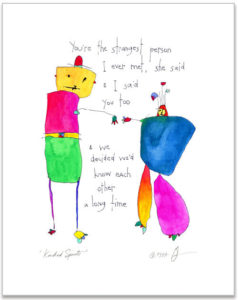

As I sat down to write this evening, I came across an article at 3 Quarks Daily titled “Patience With What Is Strange: In Praise Of Slow Art” by Chris Horner, which talks about the power of taking our time to ingest or digest things that seem strange, and it was that word–strange–that took me back to our lunch at Eli’s because, years ago, we found one of the Story People that said:

“You’re the strangest person I ever met,” she said

& I said, “You are too”

and we decided we’d know each other a long time

The article is full of good things not the least of which is the closing paragraph, which includes an incredible

Slow art has layers. And this is why it requires time and effort. We should see this as a good and necessary thing. If this is a kind of obstacle in the way of easy assimilation then it is an obstacle that is integral to the value of the thing itself. The mind is calmed, or disturbed, or made exultant by the art that rewards us for our goodwill and our capacity to take our time.

Then he closes with an incredible Nietzsche quote:

One must learn to love.— This is what happens to us in music: first one has to learn to hear a figure and melody at all, to detect and distinguish it, to isolate it and delimit it as a separate life; then it requires some exertion and good will to tolerate it in spite of its strangeness, to be patient with its appearance and expression, and kindhearted about its oddity:—finally there comes a moment when we are used to it, when we wait for it, when we sense that we should miss it if it were missing: and now it continues to compel and enchant us relentlessly until we have become its humble and enraptured lovers who desire nothing better from the world than it and only it.— But that is what happens to us not only in music: that is how we have learned to love all things that we now love. In the end we are always rewarded for our good will, our patience, fair mindedness, and gentleness with what is strange; gradually, it sheds its veil and turns out to be a new and indescribable beauty:—that is its thanks for our hospitality. Even those who love themselves will have learned it in this way: for there is no other way. Love, too, has to be learned.

We don’t always have the luxury of taking the afternoon to hang out, but one of the things I have learned about love is to take any opportunity that presents itself, or better yet, make space where there doesn’t seem to be any. We have been intentional about learning that “we should miss it if it were missing.” And Nietzsche is right: it does continue to enchant us relentlessly.

The chorus of the first song I ever wrote with Billy Crockett says,

it’s an open heart

it’s a work of art

it’s the basic stuff

that makes another

picture of love

Thirty-four years on, I’m still finding layers and I am still enchanted by the slow art of love.

Peace,

Milton

Milton, thank you for sharing your thoughtful and layered answer to Ginger’s great question. Cheers to 34 years.