It’s an odd connection, I suppose.

I was reading Rebecca Solnit’s Orwell’s Roses and she was describing a painting of one of his English ancestors–a painting of “gentility”: an English country house and the men clothed in their privilege–and then went on to talk about what was “outside the frame of the painting,” which was that the money that got them their houses and finery was made through the slave trade. To leave all that outside the frame meant they could see themselves as gentle men rather than brutal ones.

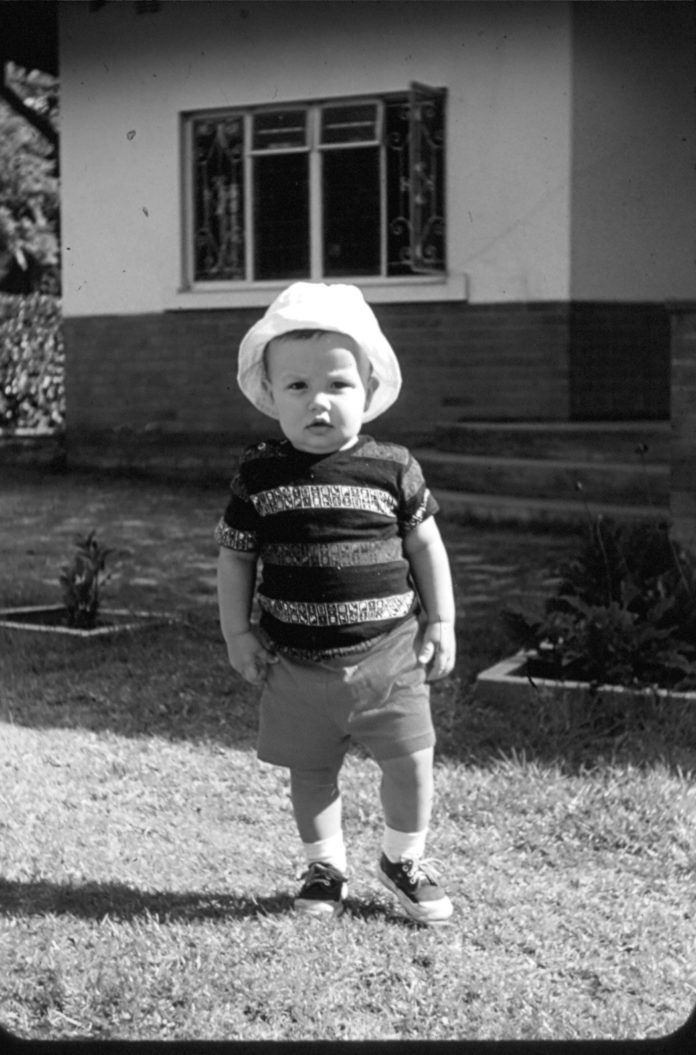

Her point notwithstanding, I kept seeing frames in my head and the edges of photographs that define the picture. And I thought of this picture, one I keep coming back to when it comes to thinking about who I am. It was taken in the front yard of our house in Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). I have no idea how old I was, except that I lived there between the ages of one and five. I’m guessing this is somewhere in the middle of all of that.

that define the picture. And I thought of this picture, one I keep coming back to when it comes to thinking about who I am. It was taken in the front yard of our house in Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). I have no idea how old I was, except that I lived there between the ages of one and five. I’m guessing this is somewhere in the middle of all of that.

I wrote about this picture in my book This Must Be the Place: Reflections on Home. Here is part of what I said after I wrote, “The history we construct doesn’t use facts for bricks.”

Before my beginning, my parents had stories of their own and their parents before them. My family across generations, however, have not been good record keepers. One of my mother’s uncles joined the Mormon Church and did a good deal of genealogical work as an expression of his faith, but beyond that none of us has explored much of our family tree. From the time I was small, I can recall my father telling the story of how his mother died in childbirth. He recounted how his father said the doctor offered his parents a choice: Either the mother or the child could live. She chose her son. I was in my thirties and my father in his sixties when the woman I knew as “Grandma C”—his stepmother—gave him a binder full of newspaper clippings and other things about his birth mother that she had saved over the years. From what I could tell, Dad knew nothing of the notebook until that moment. There in the brittle black and white of the aging newsprint was her obituary—she had died almost a month after he was born. After six decades, his creation story changed. How he came to be happened differently than the story he had trusted with his life. I’ll never forget the look on his face.

My parents and my birth certificate say I was born in Corpus Christi, Texas, but I had my first birthday on a trek from Texas to New York City, on our way to Africa; my first memory of myself is the picture of me standing in the front yard of our house at 15 Dale Carnegie Road in Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia. I was about two. I don’t remember the photograph being taken, or standing in the yard, or even much of living in Bulawayo. I hold the memory because I have seen this snapshot so many times—the shorts, the striped T-shirt, the white hat, the little sneakers, the one lifted foot—to the point that I feel like every picture I remember of that house on Dale Carnegie Road had me standing in the front yard as though I were some sort of yard art. I’ve imagined people driving by and thinking, “There’s that little boy again. Don’t they ever let him go inside?” The moment is so specific it has become timeless: I am always in the yard on Dale Carnegie Road. Milton starts here.

I remain fascinated that the photograph catches my left foot in the air. I wonder where I was going.

Outside of the frame were my mother, my father, my baby brother, Nina, my nanny, and a big Collie whose name I can’t remember. Far outside the frame and across the ocean were grandparents and an aunt and uncle I knew nothing about, along with a nation that called me a citizen but wasn’t home.

These days, we talk about reframing issues or situations as a way of getting a fresh look at them. It creates an image of taking off the fancy gold frame and replacing it with a more modern acrylic one, or vice versa. Perhaps a fresh look is changing the frame, or looking beyond it; moving the borders to include a larger view that makes visible connections that had been cut off.

Like I said, it’s an odd connection between a painting of an English country house and a picture of little Milton in the front yard, always on his way to somewhere outside the frame.

Peace,

Milton

Powerful story here, Milton. Thanks

Milton, thanks for the beautiful story.