For thirty years or so I have written every day during Advent (or tried to) as a way of focusing my heart and mind on the season. For the last fifteen or sixteen years, those musings have found their place here on the blog. This year marks my first Advent with the good people at Mount Carmel Congregational Church, so my first entry in my journal is my sermon for today, “Shocking Hope.”

In a way, the adjective is redundant. Hope is a shocking thing, a disruptive grace that peppers our lives with a sacred tenacity. I hope you find words here that speak to you. I look forward to the journey together.

________________________

Advent begins each year as we light the candle of hope.

Hope is a difficult word to define.

We live and speak like we know what it means—and in some sense we do—but an actual definition is not easy to give. We say things like, “I hope you win,” which sound like hoping and wishing are synonyms, but hope is stronger than that. Hope is also different than optimism; it’s more layered than simply trusting things will get better. One of my favorite writers, Rebecca Solnit, says hope thrives in uncertainty when anything can happen then, well, anything can happen; thus, we have reason to hope.

As Nancy said in the introduction to our reading, Isaiah’s words are part of a longer lament for the way life had become. A lament is more than simply decrying or complaining about the state of things. It is an expression of sorrow, of grief for the way things have gone, perhaps even an admission of fault, and it is a statement of hope that things will not always be the way they are—that the uncertainty created possibility.

Despair takes hold when we convince ourselves that nothing can change. Certainty and cynicism are cousins. Isaiah cried out for God not to give up on people, even when they couldn’t get out of their own way. He trusted that anything could happen even though things looked bleak and he felt deserted by God. Still, he prayed, “You are our potter; we are all the work of your hand.”

I got to be a potter once. Well, for a few minutes. Ginger and I were in Turkey as a part of a sabbatical grant she received, and we had toured a small pottery factory in Istanbul to see how they made the beautiful pieces they had in their shop. They asked if anyone wanted to try their hand at the potter’s wheel and, being the extrovert I am, I volunteered. They gave me this enormous pair of colorful balloon pants to put on over my trousers and a smock to go over my shirt and then seated me behind a big flat wheel with a foot pedal on one side. They put some clay in the middle and then gave me instructions on how to make the wheel turn so I could begin to fashion a bowl out of the figureless lump of clay in front of me.

There were so many things to keep in mind. I had to keep my hands wet and not let the wheel move too slowly or too quickly. I had to learn how much pressure to apply so the clay would begin to take shape. I managed to make a thing that looked something like a bowl; mostly I learned to appreciate the artistry and skill required to make some of our most basic things: plates, bowls, pitchers, cookware.

Other than becoming more motorized, the art of making pottery has not changed that much since Isaiah used the metaphor. To say God is the potter and we are the clay that gets shaped into meaning is, for one thing, to say that God keeps up with a lot of details—with all of the details—of creation. Just as the potter has to attend to the speed of the wheel and the consistency of the clay and the moisture that makes it pliable and the amount of pressure it takes to shape it into something, God sees all the variables at play in our lives.

That is not to say God controls them or dictates what happens; that’s one place the potter metaphor breaks down. In fact, at the heart of the metaphor is what can’t be controlled. No matter how artful the potter, how deft they are at shaping the clay, they are at the mercy of the ovens—the kiln.

The pottery has to be fired at two points in the process. First, it has to be dried after it is shaped to pull the moisture out and solidify the object. Second, it has to be fired after it has been painted or glazed to seal the clay so it can be used. Often times, at either stage, the pottery cracks in the kiln, often not because of anyone’s mistake, but because that’s how it goes sometimes.

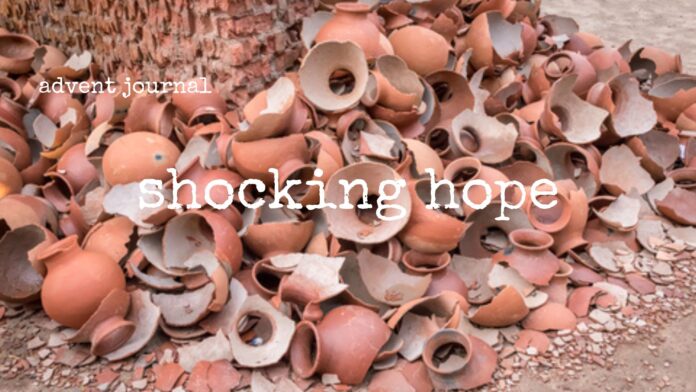

Yes, we are wonderfully and uniquely created in the image of God and worthy to be loved—we are God’s pottery—and sometimes we are broken and cracked by things we cannot control. And here’s the other place the metaphor breaks down.

In actual pottery-making, the pots that crack and break in the kiln are thrown away. The clay cannot be melted and reused. The cracks can never be adequately repaired. A broken pot is a useless one, regardless of how it gets broken.

God’s artistry tells a different story: anything can happen. Just as we can be wounded and broken by life, we can be reshaped and healed by grace. That was the hope that Isaiah expressed when he prayed, “Don’t give up on us.” He trusted God was still at work in the middle of all the broken pieces.

That same trust lies at the heart of the shocking hope of Advent. All is not lost. Even though life is difficult, it is not futile. All the crumbled bits of clay of our circumstances hold the possibility of new creation, of something unexpected—of hope, not because everything will work out in the end but because anything can happen; we can be shaped and restored by God’s love right here in the middle of the mess.

And so we circle around to tell that story during Advent every year to shape our faith once again, much like the potter spins the wheel to shape the pot. The quote at the end of the candle lighting says it well:

What good is it to us that Mary gave birth to the son of God two thousand years ago, and we do not also give birth to the Son of God in our time and in our culture? We are all meant to be mothers of God. God is always needing to be born.

I know I am mixing metaphors, switching from pottery to pregnancy, but both are talking about hope, about trusting what we don’t completely understand.

We’ve all heard the Christmas story. We know the characters. We have layers and layers of years and tradition that we have received and continue to pass down. Those are good things, and in this season we need to be about more than simply repeating ourselves if the story is going to shape us in fresh ways.

It takes both imagination and courage to choose hope as our way of looking at the world, to imagine ourselves as vessels shaped by God, or as those giving birth to God’s presence in our time. The truth is the world is a broken and beautiful, vicious and engaging, mutilated and loving, a terrible and wonderful place.

Having the courage and imagination—the hope—to hold both of those truths is what it means to hope. Hope knows things aren’t just going to work out. Hope understands that we don’t always know the consequences of our actions, though often we can make a pretty good guess. To live hopefully is to live as though every word and every action has an impact, a consequence, to live like we are all connected, to live as though love is what matters most, to live as though all of these motions we are going through, from lighting candles to singing hymns to sharing Communion are crucial acts of imagination and intention—of hope.

We can’t see what is coming, but we are here in these days to give birth to Christ in our time. We are here to see what God can shape out of the shards of our lives.

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in

We are here to foster hope in one another, no matter what happens. And we hope when we trust that anything can happen. God has not given up on us; let us live with hope and not give up on us either. Amen.

Peace,

Milton