I preached this morning at North Haven Congregational Church. Here is what I had to say.

______________________________________

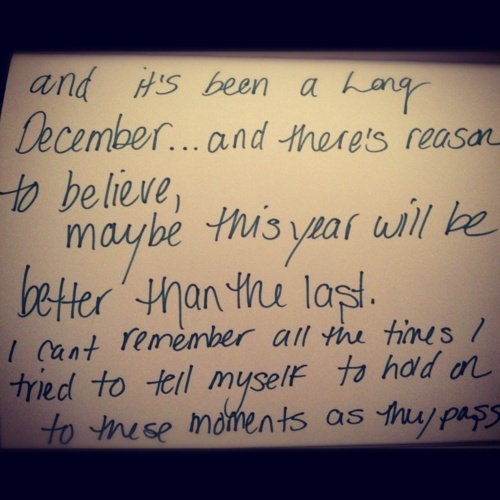

For a number of years now, I have marked the end of the year with a song by Counting Crows that begins

a long december and there’s reason to believe

maybe this year will be better than the last

And almost every year–at least for the last several–it does not seem to be the case. I’m not sure I think 2019 was a better year than 2018. We sing in our carols about Jesus’ birth meeting the hopes and fears of all the years, what does that mean for 2020? What does hope look like in our lives?

Twenty-twenty. It sounds different, doesn’t it. We have to rethink how we write the dates down and adjust to the visible reminder than time is going quickly. Wasn’t the turn of the century just a few years ago? How is it that we are only five years away from this “new” century being a quarter of the way done?

If you think time is moving too quickly, look at the way Matthew tells time in his gospel. His account of Jesus’ birth begins in chapter one, verse eighteen. By the time we get to the verses we read this morning, which begin in chapter two, verse thirteen, the magi have come and gone and Herod is determined to get rid of Jesus. He was so threatened by the thought of who Jesus might become that he sent out a decree for all of the male children under two years old to be killed–what we, in the liturgical tradition, call “The Feast of the Holy Innocents.” The word feast here means a day of commemoration rather than a big meal.

Four days after Jesus birth and we are marking deaths. And death comes to us on both a global scale and on a personal one. Matthew ties the slaughter of children to the deep pain the Hebrew people had known in their past: Rachel weeping unconsolably for her children. What was happening was not new, it was just happening to them.

Professor Esau McCaulley writes that we commemorate the feast because,

This feast suggests that things that God cares about most do not take place in the centers of power. The truly vital events are happening in refugee camps, detention centers, slums and prisons. The Christmas story is set not in a palace surrounded by dignitaries but among the poor and humble whose lives are always subject to forfeit. It’s a reminder that the church is not most truly herself when she courts power. The church finds her voice when she remembers that God “has brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble,” as the Gospel of Luke puts it.

But then he makes it personal:

But how can such a bloody and sad tale do anything other than add to our despair? The Christmas story must be told in the context of suffering and death because that’s the only way the story makes any sense. Where else can one speak about Christmas other than in a world in which racism, sexism, classism, materialism and the devaluation of human life are commonplace? People are hurting, and the epicenter of that hurt, according to the Feast of the Holy Innocents, remains the focus of God’s concern.

Journalist Nicholas Kristoff wrote an op/ed this week for the New York Times entitled “This Has Been the Best Year Ever” and had statistics to back it up.

Every single day in recent years, another 325,000 people got their first access to electricity. Each day, more than 200,000 got piped water for the first time. And some 650,000 went online for the first time, every single day.

Perhaps the greatest calamity for anyone is to lose a child. That used to be common: Historically, almost half of all humans died in childhood. As recently as 1950, 27 percent of all children still died by age 15. Now that figure has dropped to about 4 percent.

In his column, Kristof was quick to say that statistics are often hard to interpret, nor was he saying that terrible things weren’t happening, but that we needed to see that things were getting better in order to have hope. But is that where hope comes from?

I don’t think so.

I am grateful that things are improving and I think it matters greatly that we work to eradicate poverty and dismantle racism and sexism and homophobia and care for creation in a way that sustains life for us all. But progress isn’t what creates hope. Progress will not make us feel less alone. If our hope depends on things getting better, what happens when they don’t?

When Joseph found out Mary was pregnant, he was troubled. The angel appeared to him in a dream and said, first, “Don’t be afraid.” Then the angel said, when the baby is born name him Emmanuel, which means God with us. Nothing the angel said changed any of the circumstances of Mary and Joseph’s lives. None of the difficulties went away. But the fear did because they knew God was with them no matter what the circumstances.

They went to Bethlehem and the baby was born. The shepherds came. Later the magi came and brought gifts, and they also brought Herod’s wrath without realizing what they were doing. So Mary and Joseph and Jesus became refugees in Egypt, fleeing the violence of their home country. All they could do was trust that God was with them, as their ancestors had done when they fled their captivity in Egypt generations before.

Herod died. Mary, Joseph, and Jesus moved back to Nazareth. Jesus grew up and began to preach and teach and heal and then he was arrested and executed by another Herod. But that is not the end of the story. The story of God with us has continued from December to December, from disappointment to disappointment, from triumph to triumph, from birth to birth and death to death, and our hope in all those things is that God is with us and God’s love endures it all, so that we can also.

This story matters because it reveals the difficult truth that life is often filled with unjust rulers and violence and private grief and personal pain and all the rest that leaves us wishing this year will be better than the last.

And this story matters because it tells the truth that God does not deal with us from a distance, but in Jesus has joined God’s own self to our story and is working — even now, even here — to grant us new life that we may not just endure but flourish, experiencing resurrection joy and courage in our daily lives and sharing our hope with others. A hope that comes from knowing God is with us and, therefore, anything can happen.

Happy New Year. Amen.

Peace,

Milton

PS–I couldn’t quote them without including the video.

Milton:

As always, you have touched & moved me, in so many dimensions that it’s virtually unfathomable. First, with your sermon: what a beacon of light in this time of darkness, a beacon that much brighter for its *recognition* of the darkness.

Second, with the Counting Crows song/video. I’ve heard that song … ohhh … a thousand times (metaphor/hyperbole) or maybe 500 (reality). I could *hear* that first line when you quoted it. So I clicked on the video & watched it & realized that I only knew the opening & the “chorus” slash repeated lines … and upon listening to it now I was reduced to tears. Literally. (And I mean “literally” literally … ) Never been a “fan” of that song, but My God! how powerful is that sentiment (or emotion) that the singer is presenting?!?! It’s like Kris Kristofferson & Bob Dylan were lobbing thought-poems at John Prine, Leonard Cohen, and Tom Waits ….

Thank you, blessings to you, and fingers crossed & prayers tossed that “this year will be better than the last ….”

Peace always,

Mitch

Thanks, Mitch. Always good to hear from you. Any time I see your words I find myself wishing we had lived in the same place and shared the same kitchen for a little bit longer.

Peace,

Milton