I have been reading a lot about stories lately: how we tell them, how we hear them, how we live them. Telling a story is more than recounting events. In his book, The Art of Time in Memoir: Then, Again, Sven Birkets writes:

There is in fact no faster way to smother the core meaning of a life . . . than with the heavy blanket of narrated event. Even the juiciest scandals and revelations topple before the drone of, ‘And then . . . and then . . .’ . . . Memoir begins not with event but with the intuition of meaning–with the mysterious fact that life can sometimes step free from the chaos of contingency and become story. (3-4)

“The chaos of contingency.” What a great phrase. We tell the story of our lives as a way to make meaning out of circumstances. Edna St.Vincent Millay said, “It’s not true that life is one damn thing after another; it is one damn thing over and over.” Though I totally get what she is saying, maybe there’s more to the story.

One of the powerful things about following the liturgical calendar is it offers the church year in a narrative, if you will: from Advent to Christmas to Epiphany to Lent to Easter to Pentecost to Ordinary Time. The string of stained-glass words offer us the chance to tell the story of our faith in the light of what we remember, what has happened since, and what is happening now. As the old hymn says, I love to tell the story.

My favorite lines in the song are:

I love to tell the story, for those who know it best

seem hungering and thirsting to hear it like the rest.

Still, those of us who know it best often run the risk of letting if become as static as stained glass. In The Art of Perspective: Who Tells the Story, Christopher Castellani, references a passage from “A Conversation with My Father” by Grace Paley,

in which a man expresses frustration with his daughter’s refusal or inability to write a traditional narrative [about] “what happened to them next.” . . . [She] thinks . . . that she would indeed like to tell that kind of story, except that it requires a plot, “the absolute line between two points which [she’s] always despised. Not for literary reasons, but because it takes all hope away. Everyone, real or invented, deserves the open destiny of life.”

“What’s despicable about the absolute line between two points,” Castellani concludes, “is its danger of becoming a single story.” (111)

Jesus didn’t walk in a straight line; he didn’t take the shortest route from the manger to the cross to the tomb anymore than the story—or, I should say, stories—of those of us who have followed him can be told in a straight line. I find myself asking the question: what is the story? The answer is not so obvious. As James Carroll points out in Christ Actually: Reimagining Faith in the Modern Age, we must

read [the Gospels] through the lens of centuries of total war and corrupted power, trying to see how violence, contempt for women, and, above all, hatred of Jews distorted the faith of the Church I still love. Yet Jesus is elusive. If he were not, he would be useless to us. (11-12)

I know. My post is, as one of my professors once critiqued a paper, quoteful, and the stuff that has stuck to me as I have been reading is heavy and disquieting. As our political discourse devolves into a poor imitation of middle school recess (with apologies to middle schoolers), I have chosen to turn my ears to those who have to fight to be heard. Folks Bryan Stephenson, William Barber, Tim Tyson, Willie Jennings, and Michelle Alexander have opened my eyes and heart to new levels of understanding and grief as they tell the stories of race in our country that we, as white people, have chosen, too often, not to hear. The Christ of Conquest is a strain of stories across centuries that breaks my heart. As Don Henley sings,

we satisfy our endless needs

and justify our bloody deeds

in the name of destiny

in the name of God

But the Christ of Conquest is not the only story. While those who stand in that lineage from Constantine to Franklin Graham continue to value power over people and think it matters more to be right than to be love, there are the stories of Jesus that have been told in the lives of Rosa Parks, Dorothy Day, Sojourner Truth, Martin Luther King, to name a few, as well as the stories of those whose names are known in their towns, and on the streets where they incarnate love in the same way Jesus did as he walked the dusty roads in Palestine, on the way to nowhere in particular other than whoever was in front of him.

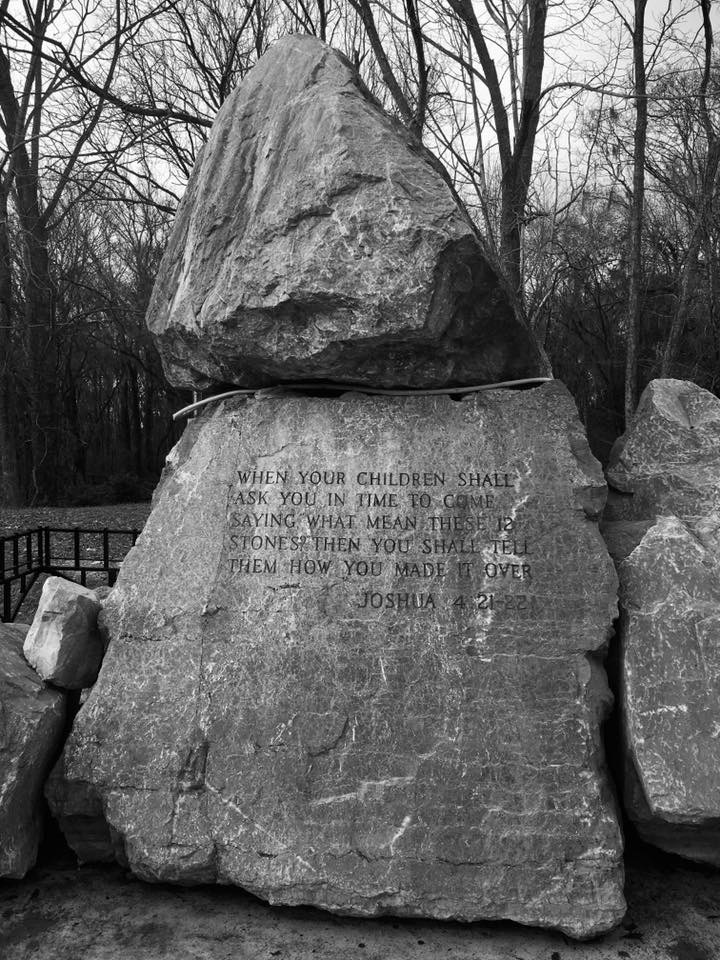

Last week, I walked across the Edmund Pettis Bridge in Selma, Alabama. At the base of the bridge on the other side of the river, where so many were beaten on Bloody Sunday, was a rock monument inscribed with the words from Joshua 4:21-22:

When your children shall ask you in times to come, saying,

“What mean these stones?”

Then you shall tell them how you made it over.

I found myself wondering how we will explain the stones we are stacking in these days, what stories we will tell. What stories will be told about us? How will the way we live out our faith affect the ways people will tell the stories of Jesus in years to come?

A friend wrote this week and asked me to write a prayer for their service this Sunday. I think it’s a good way to end this post and begin my Lenten story this year.

God of Flesh and Blood,

We gather to be reminded that you are

a God who deals in relationships, not in rhetoric;

a God who is hip-deep in humanity, not hypotheticals.As we follow Jesus to the Cross once again,

let us see in ways we have not seen

that when Jesus said, “Blessed are the poor,”

he knew them by name;

when Jesus said, “Blessed are those who mourn,”

he wept with them;

when Jesus said, “Blessed are the peacemakers,”

he waged peace alongside them.We gather to be reminded that you call us

to love as unflinchingly as you have loved us:

face to face, shoulder to shoulder, heart to heart.

May those we encounter see your love in our lives. Amen.

Peace,

Milton

Thank you Milty. What a beautiful way to start the Lenten season with your beautiful words.

Thanks, Chuck.

Milton, thank you for this. I am reading The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead. I recommend it.

Lenten blessings…

Leah

I’ll add that to my reading list.

As the great great granddaughter of a man who had 18 slaves in the mid 1800s, I read these works wondering. My family did not record in writing or pass down stories, so I cannot know more than the census reported 18 slaves. And by the way, I am leading a retreat Th/Fr and talk about “quoteful”. So grateful for shared wisdom along the way.

Thank you. I, for one, am fond of the quoteful style. 🙂

Thanks. It reminds me that I am only one of the voices in the choir.

Welcome back, Milton, and thank you. : ) You are one of my Lenten blessings. I hope those blessings come back to you multiplied many times over.

So glad to hear your voice again; Milton!!!