For the month of September I am preaching from passages in the Letter from James, a small book towards the end of the New Testament that is an exercise in practical theology. This week’s sermon drew from James 1:17-27.

____________________________

One of the things I remember about the beginning of the pandemic when we were in lockdown was how much I detested being on Zoom. And I couldn’t figure out why. I am an off-the-charts extrovert (you probably didn’t know that), so I imagined having the chance to see and talk to others from our separate isolations would be a good thing, but it wasn’t.

After a couple of weeks, I came across an article that talked about people’s struggles with Zoom and it listed my problem. It said the reason we were having trouble was we were not used to seeing myself on screen. I know didn’t like seeing my facial expressions as I was making them. I felt disembodied somehow, even as I was trying to participate.

In natural conversation, we don’t see ourselves as we talk to others. Our expressions come from the inside out. With Zoom we were, quite literally, beside ourselves—or in front of ourselves, actually—which made us self-conscious; I realized that’s what made me uncomfortable.

It also offered a solution by showing how to turn off “self-view,” so that we only say those we were talking to. That little tip saved me from my frustration. I don’t need to see myself while I’m talking to other people. I do, however, need to remember I’m on camera and that others can see me.

Even though the writer of the letter attributed to James had no concept of being on a Zoom call, he did know something about how we look at ourselves, and he knew that it takes effort and intention for us to remember who we are as we move through the various situations that come our way.

A mirror was technology he understood, when it came to seeing a reflection of ourselves. We don’t have to stand in front of a mirror to remember what we look like; if we did, we wouldn’t get much done. But, he said, someone who describes themselves as a follower of Christ and still lashes out in anger, or makes damaging statements about others, or does things that take advantage of others is like a person who can’t remember who they are if they aren’t staring at themselves.

One of the first thing that comes to mind for me are those moments from time to time when someone in the public eye is caught on an open mic making a racist, or misogynist, or homophobic statement. Almost every time, part of their apology is to say something akin to, “That’s really not who I am.”

And yet, it is in some way. They said and did those things. They need to go back to the mirror and check in.

But let’s not talk about them. Let’s talk about us and how we remember who we are. Theologian Katie Van Der Linden wrote,

When you walk away from a mirror, you can still catch glimpses of yourself in windows and other reflective surfaces. So don’t forget who you are. You are a faithful follower of Jesus, whether you’re stranded on a desert island or you’re in the middle of Manhattan. Faith is about what God sees and what the world sees; they are not separate. Hear the word, do the word, follow the word, alone in your car or on a crowded bus. The journey is yours, but others may notice.

Who do we see when we catch a glimpse of ourselves?

Are we being the people we think we are? Do our lives reflect the image of God that lives in us?

The way to answer those questions affirmatively, our passage says (and I love our translation this morning) is to

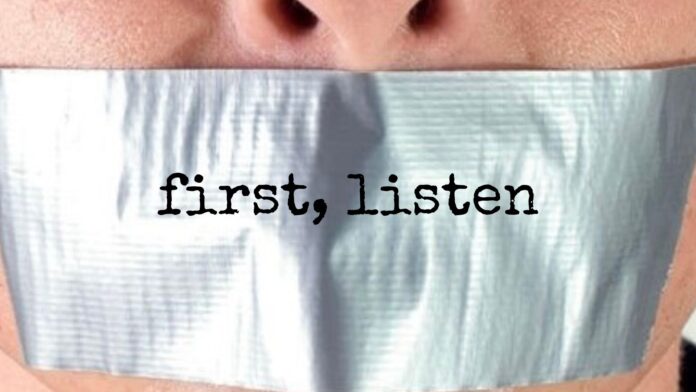

Lead with your ears, follow up with your tongue, and let anger straggle along in the rear. Human indignation doesn’t accomplish God’s justice.

In a way, that sounds like what we learned as kids: stop, look, and listen.

Listen first, then speak—when we have something to contribute—and leave our outrage behind. And hear the last sentence again: “Human indignation doesn’t accomplish God’s justice.”

“My life was changed by someone shouting at me or by a long rant on Facebook” is, I feel fairly confident, a sentence that no one has ever said. Anger is part of who we are, and it is an appropriate response when we have been hurt or someone we care about has been hurt. Outrage, on the other hand, is not useful in building relationships, even when we’re right.

Hearts and minds are changed in conversation, in relationship—by listening and speaking and standing up for and with those who far too often get shouted down. God’s justice is accomplished, our verses say, by reach out to the homeless, lonely, and loveless in their plight, and guarding against corruption.

Listen, then talk. Don’t use outrage as a motivational tool. Take care of those who need to be taken care of. This little letter attributed to James is full of accessible wisdom. It holds a unique place among New Testament books for its practicality. He offers theology with skin in—stuff that changes the way we think about everyday life. We are going to keeping reading this letter throughout September.

This morning, James asks that we look at our reflection to see how much the image of God shines through. We were created to incarnate love to one another. Is that who we see when we look at ourselves? Amen.

Peace,

Milton