I love that the story of Samuel falls on MLK weekend, thanks to the lectionary. Here is where the two stories took me this week.

_____________________________

Today is the second Sunday of Epiphany, if we mark time by the liturgical calendar. As we know, epiphany is a word that means “awakening,” and points us to the sages who followed the star to the manger–although they had no idea it was Epiphany.

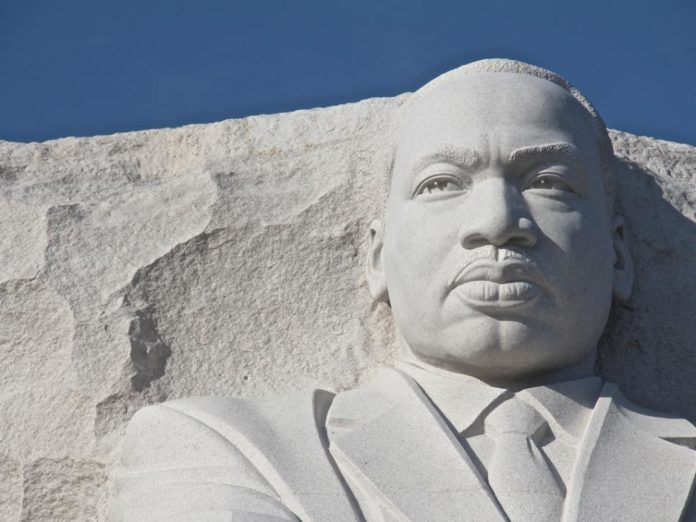

If we mark time by our American calendar, this is the Sunday when we honor the legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Tomorrow we will celebrate him with a national holiday.

On the night of January 27, 1956, in the middle of the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott, Dr. King got a phone call at his home telling him if he didn’t get out of town they were going to blow up his house and kill him and his family. He was twenty-seven years old. He recounted later that he hung up the phone and went into the kitchen to pray. In the silence, he said he heard a voice call him by name: “Martin Luther, stand up for truth, stand up for justice, and stand up for righteousness.” His epiphany that night led him to lead us and to change how we look at and listen to one another, and, perhaps, how we listen to God.

Our text for this morning deals with another call in the middle of the night—this one to Samuel, a young boy to whom God spoke out of the darkness. Let us listen to the part of the story told in I Samuel 3:1-10 (CEB):

Now the boy Samuel was serving the Lord under Eli. The Lord’s word was rare at that time, and visions weren’t widely known. One day Eli, whose eyes had grown so weak he was unable to see, was lying down in his room. God’s lamp hadn’t gone out yet, and Samuel was lying down in the Lord’s temple, where God’s chest was.

The Lord called to Samuel. “I’m here,” he said.

Samuel hurried to Eli and said, “I’m here. You called me?”

“I didn’t call you,” Eli replied. “Go lie down.” So he did.

Again the Lord called Samuel, so Samuel got up, went to Eli, and said, “I’m here. You called me?”

“I didn’t call, my son,” Eli replied. “Go and lie down.” (Now Samuel didn’t yet know the Lord, and the Lord’s word hadn’t yet been revealed to him.)

A third time the Lord called Samuel. He got up, went to Eli, and said, “I’m here. You called me?”

Then Eli realized that it was the Lord who was calling the boy. So Eli said to Samuel, “Go and lie down. If he calls you, say, ‘Speak, Lord. Your servant is listening.’” So Samuel went and lay down where he’d been.

Then the Lord came and stood there, calling just as before, “Samuel, Samuel!”

Samuel said, “Speak. Your servant is listening.”

The story from the life of Samuel was one that engaged me as a young boy because I imagined him at my age. I didn’t understand how his mother could have sent him to live in the Temple, but I could see him waking in the night and going to Eli, thinking the old man had called him. But the story is bigger than a little boy.

Samuel’s mother was named Hannah. She had a hard life, to put it mildly. Her husband had two wives and the other woman had given birth to several children and Hannah had none. As a result, the husband played favorites and discriminated against Hannah because she had not given birth. Hannah went to the temple and pleaded with God to give her a child. Her prayer was so fervent that Eli, the priest, saw her without hearing her and thought she was drunk. Hannah told him her story and Eli said he hoped she got what she asked for.

She became pregnant and gave birth to Samuel. Then she decided the best way to say thank you was to give the boy back to God. We need to understand here that the boy was her ticket to some equity in the way she was treated by her husband, but she chose a story bigger than her own—beyond the injustice and misogyny of the time. Once the child was weaned, she took him to the temple and left him there for Eli to mentor as a way of saying thank you to God.

Eli was–what’s the theological term?–a hot mess as a priest. By the time Samuel came to live with him, Eli was old. His sons were priests alongside him, but they used their positions as opportunities to enrich themselves and take advantage of whomever they could. All of this had gone on a really long time, even before Samuel came to the temple.

As our passage noted that a word from God had become a rare thing by the time Samuel heard his name called out in the night. He went to Eli because he didn’t think anyone else was there. The drowsy priest said, “I didn’t call you. Go back to bed.” It happened a second time, and then a third. By then, Samuel wasn’t the only one who was awake, and Eli had a sense that more was going on, so he gave Samuel different instructions: “Next time answer, ‘Speak, Lord. Your servant—your follower, your disciple—is listening.’”

Samuel’s childlike response makes his answer sound so doable. But to actually say to God, “I’m listening”—and mean it—is a brave thing to say. When Samuel listened, God told him to go to breakfast the next morning and let Eli know that his blindness was both a physical reality and a metaphor: he and his sons had lost sight of their calling and their humanity and were going to be punished for their abuse of their office. The whole house was about to come down.

When Eli asked Samuel what God had said, Samuel didn’t hold back. He chose to tell the truth.

I had a chance a few years ago to visit the house where Dr. King was living in Montgomery, Alabama when he got the call that threatened his life–and when he heard God’s call that followed it. Shirley Cherry, the woman who was leading our tour, told us the story and said, “He had a choice. Dr. King had a privileged life. He didn’t have to do what he did.” Her choice of words jumped out at me: he had a privileged life. Yes, he got to study at Boston University. He did have some advantages others did not. Yet, when he came to Durham, North Carolina, just days before he was assassinated, to meet with an interracial group of ministers, they had to meet in the private home of one of the pastors because there was not a restaurant in town that would allow them to eat together.

Yet, she said, he had a choice.

The night he stood up to speak to the sanitation workers in Memphis, Dr. King began his speech with these words:

As you know, if I were standing at the beginning of time, with the possibility of general and panoramic view of the whole human history up to now, and the Almighty said to me, “Martin Luther King, which age would you like to live in?” — I would take my mental flight by Egypt through, or rather across the Red Sea, through the wilderness on toward the promised land. And in spite of its magnificence, I wouldn’t stop there. I would move on by Greece and take my mind to Mount Olympus. And I would see Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Euripides and Aristophanes assembled around the Parthenon as they discussed the great and eternal issues of reality.

He kept saying, “I wouldn’t stop there,” as he moved through different historical epochs and then he said,

Strangely enough, I would turn to the Almighty, and say, “If you allow me to live just a few years in the second half of the twentieth century, I will be happy.” Now that’s a strange statement to make, because the world is all messed up. The nation is sick. Trouble is in the land. Confusion all around. That’s a strange statement. But I know, somehow, that only when it is dark enough, can you see the stars. And I see God working in this period of the twentieth century in a way that [people], in some strange way, are responding — something is happening in our world. The masses of people are rising up. And wherever they are assembled today, whether they are in Johannesburg, South Africa; Nairobi, Kenya; Accra, Ghana; New York City; Atlanta, Georgia; Jackson, Mississippi; or Memphis, Tennessee — the cry is always the same — “We want to be free.”

And another reason that I’m happy to live in this period is that we have been forced to a point where we’re going to have to grapple with the problems that [people] have been trying to grapple with through history, but the demand didn’t force them to do it. Survival demands that we grapple with them. [People], for years now, have been talking about war and peace. But now, no longer can they just talk about it. It is no longer a choice between violence and nonviolence in this world; it’s nonviolence or nonexistence.

Samuel made a choice and rose to greatness. Martin Luther King made a choice and was murdered for it. The call to follow God is not a guarantee for everything to turn out just as we hoped. It is not a promise that if we follow God we will be set for life.

It is a choice to do justice, love kindness, and walk humbly. Or not.

One of the heartbreaking images for me, as I watched the invasion of the Capitol, was to see someone carrying a “Jesus Saves” sign. Condemning the violence and condemning the attempt to baptize it are not hard choices. But choosing to examine whether our lives–our words, our practices, our actions, our silences–feed the fires of hatred and prejudices or join a river of hope that will let justice roll down like water is not always so easy because it means we have to listen, like Samuel–and listen hard–and we have to make the daily decisions, like Dr. King, to live out our understanding that life is not primarily about us. We are not the stars of the show. We are not the ones who deserve our privilege and our advantages. We are the ones whom God is calling to do more than say what happened at the Capitol was wrong. I’ve heard some people say, “This is not who we are.”

Actually it is who we are, and who we have been—but it is not who we have to be.

I woke up Saturday morning to an article by Krista Tippett, the host of the On Being Project. She wrote about an e-mail she had received from a woman named Whitney Kimball Coe who works with the Center for Rural Strategies and lives in East Tennessee. Monday night, Whitney’s daughter took a bad fall and required surgery. She wrote:

You know, our hospital experience put us directly in the path of so many wonderful East Tennesseans. Nurses and technicians and doctors, the other parents waiting in the ER, the parking attendant, the security guard. I’m sure many of them didn’t vote as I did in the last election and probably believe the events of Jan 6 were mere protests, but they responded to our trauma with their full humanity. I’d forgotten what it feels like to really see people beyond their tribe/ideology. It broke something open in me. I’ve been living in a castle of isolation these many months and it’s rotted and blotted my insides. I’m aware of contempt, anger, and maybe even paranoia coursing through my veins, and I wonder if that’s just a snippet of where we are as a nation. Why is our righteous indignation and disgust so much easier to flame than our compassion?

It makes me realize that there is no substitute for coming into the presence of one another. No meme nor Twitter post nor op-ed nor breaking news nor TED talk can soften and strengthen our hearts like actually tending to one another. . . . We have to keep showing up so we don’t lose ourselves to bitterness.

Krista Tippett ended her article by saying,

We are creatures made, again and again, by what would break us. Yet only if we open to the fullness of the reality of what goes wrong for us, and walk ourselves with and through it, are we able to integrate it into a new kind of wholeness on the other side. Our collective need for a new kind of wholeness might be the only aspiration we can share across all of our chasms right now.

Longings, too, can be common ground. A shared desire not to be lost to bitterness. A clear-eyed commitment that what divides us now does not have to define what can become possible between us.

Choosing to do the hard work of togetherness is more than agreeing to disagree. If we are going to choose to not be lost to bitterness, then we will have to choose to speak the truth in love, like Samuel. We will have to choose to trust nonviolence as strength against brazen aggression and prejudice, like Dr. King. We have to choose to ask honest questions and to offer honest answers. We have to choose to listen to God and to one another. Samuel heard God’s call because he woke up. Eli slept through the whole thing because he had long since lost sight of what God wanted to do through and with him. May we continue to awaken and choose to listen. Amen.

Peace,

Milton

Dan Rather, CBS anchor, once asked Mother Teresa what she said during her prayers. She answered, “I listen.” So Dan turned the question and asked, “Well then, what does God say?” Mother Teresa smiled with confidence and answered, “He listens.”

“Actually it is who we are, and who we have been—but it is not who we have to be.”

Thank you, Milton. I, too, love that Samuel’s story aligned with MLK weekend.