My day started with jolts from both my morning coffee and, then, these words from Howard Thurman:

The will to understand other people is a most important part of the personal equipment of those who would share in the unfolding idea of human fellowship. It is not enough merely to be sincere, to be conscientious. This is not to underestimate the profound necessity for sincerity in human relationships, but it is to point out the fact that sincerity is no substitute for intelligent understanding. (Deep is the Hunger 30)

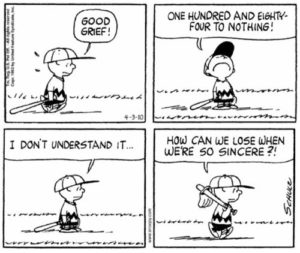

I’m going to give you the full quote in pieces because I kept stopping to jot down things as I read. And when I read the sentence that said, “It is not enough merely to be sincere,” an image of my father preaching popped to my mind. I could see him standing in the pulpit at Westbury Baptist Church in Houston, where he pastored for seventeen years, describing a Peanuts cartoon with Charlie Brown walking, hit baseball bat over his shoulder and his head hanging low and saying, “One hundred and eighty-four to nothing, and we were so sincere.” His point was we can be sincerely wrong. Sincerity, on its own, isn’t worth much.

I did a Google search and found the cartoon. Dad was pretty close on the quote, as you can see, but Charlie Brown’s actual question hit me even more directly: “How can we lose when we are so  sincere?” For Thurman, the answer to that question appears to be an act of will. To connect with one another across whatever lines we might perceive requires more than meaning well; it requires a choice, or, as he puts it, an act of will.

sincere?” For Thurman, the answer to that question appears to be an act of will. To connect with one another across whatever lines we might perceive requires more than meaning well; it requires a choice, or, as he puts it, an act of will.

The will to understand requires an authentic sense of fact with references to as many areas of human life as possible. This means that we must use the materials of accurate knowledge of others to give strength and direction to the will to understand. . . . It is easy to say that we understand other persons whose culture and background are different than ours, merely because we are kind to them or willing to make personal sacrifices on their behalf. (30)

The will to understand. The phrase challenges me to ask myself if it is a choice I am willing to make indiscriminately. To choose to understand means to do a lot of work to learn, rather than assuming we know much about anything. Stacey D’Erasmo describes intimacy—which feels, to me, like the incarnation of the will to understand—as, “Making visible what, without you, I would perhaps never have seen.” (The Art of Intimacy 121) At another place in her book, she says,

Intimacy redraws the characters’ map of the world and their place within it. Intimacy snatches you out of yourself, shows you how small you are in relation to the rest of the universe. . . . Intimacy brings a liberating knowledge of the foreign, the beyond, of the limits of the self in a much bigger universe. (34, 37)

Though she is talking about the ways in which writers create worlds and relationships in fiction, I can’t help but feel she is talking about reality as well—or, at least, that is how I am choosing to read her words. To choose to do what it takes to truly understand each other means to choose to be vulnerable: to choose to admit I am not self-contained, that I am not the star of this movie. We are an ensemble cast. Back to Thurman:

Unless there is a constant heightening of the sense of fact to give guidance to our will to understand, we are apt to substitute sentimentality for understanding, softness for tenderness, and weakness for strength in human relations. (30-31)

His words remind me of a story I heard from a black pastor in Durham who worked in a part of town that has not experienced much benefit from the city’s economic resurgence. A group from a predominantly white church in town came to spend a week helping in the neighborhood, which is made up, predominantly, of people of color. The folks from the church wanted to make a difference. They wore t-shirts with the name of their church on the front. On the back were Jesus’ words from Matthew 25:40: “Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.”

We are apt to substitute sentimentality for understanding, yes. And sometimes we choose anger or indifference, or we choose not to do the work it takes to see more than our point of view. None of those choices is a once-and-for-all kind of deal. When Ginger and I perform weddings, we often say that the promises made in the ceremony have to be kept everyday; that’s how you keep a promise: over and over and over. So it is with the promises we make to each other, and to God. We have to keep them on a daily basis, and reinterpret what it means to keep them as we learn more about each other. Meaning well is not enough.

Somewhere in writing all of this, I began to hear Nick Lowe’s “(What’s So Funny ‘Bout) Peace, Love, and Understanding” in my head. The second verse says,

and as I walked on through troubled times,

my spirit gets so downhearted sometimes,

so where are the strong?,

and who are the trusted?,

and where is the harmony?

sweet harmony’cause each time I feel it slipping away, just makes me wanna cry,

what’s so funny ’bout peace, love, and understanding?,

what’s so funny ’bout peace, love, and understanding?

I don’t choose to understand if I decide who you are first. If I am going to be able to see things I can’t see without you, I have to choose to see you, first. And choose to be seen. I’ll let Nick sing us out . . .

Peace,

Milton

I believe, sometimes, a person’s will-to-understand is encumbered by an unwillingness to feel the pain of understanding.

That’s tomorrow’s post. 🙂

Love this version of that song.

Thank you Milty.